The Lilith Blog

May 24, 2017 by Judith Rosenbaum

When You’re a Woman and You Need to Say Kaddish

It was November, 2013, my first week back at work after my father’s rapid death from a fall two weeks before. On my lunch break, I was in the middle of a very crowded crosswalk on 6th Avenue, in the West 40s of Manhattan, when my cell rang. It was from my synagogue; Rabbi Felicia Sol was returning my call after I had left a voice mail message informing the “life cycle emergency” department of Dad’s death. Not being a regular attendant at Sabbath services, I was touched that she had reached out to me. I ducked into a glassed-in corporate garden on the corner of 6th and 43rd, where we spoke in the relative privacy of that very public space.

It was November, 2013, my first week back at work after my father’s rapid death from a fall two weeks before. On my lunch break, I was in the middle of a very crowded crosswalk on 6th Avenue, in the West 40s of Manhattan, when my cell rang. It was from my synagogue; Rabbi Felicia Sol was returning my call after I had left a voice mail message informing the “life cycle emergency” department of Dad’s death. Not being a regular attendant at Sabbath services, I was touched that she had reached out to me. I ducked into a glassed-in corporate garden on the corner of 6th and 43rd, where we spoke in the relative privacy of that very public space.

I have never been that religious a Jew; I was raised in the Reform tradition by a mother who’d been raised Orthodox and a father who’d been raised an ethnic, secular Jew. Though Reform, my mother always lit the candles and said the Sabbath blessings before dinner on Friday nights. Despite my dad’s upbringing, his wishes were for a traditional Jewish burial, complete with a cotton shroud and a shomer—a volunteer to guard the body from hospital deathbed to grave. Our family had completed the one-week shiva tradition the week before.

I told Rabbi Sol that the hardest thing at that moment was being surrounded by people going about their business. They seemed rushed and focused, certainly unaware of the heartbreaking pain and loss I felt inside, which was surely not evident on my face.

Rabbi Sol said, “That’s what saying kaddish is for.”

- 3 Comments

May 23, 2017 by Patricia Grossman

Witness to Mass Incarceration

At the age of three, Evie Litwok used to watch her father pray. Every day, she would stick her arm out and he would put the leather strap around both their arms. Her parents were Holocaust survivors, and during the war her father had looked up to G-d and said, “If you allow me to live, I will honor you every day.” He kept his promise, davening daily, always with a smile. When Evie grew up, she was not particularly religious, attending temple only on the High Holidays. Yet the day she went to prison, she knew she wanted a siddur. She needed to pray.

At the age of three, Evie Litwok used to watch her father pray. Every day, she would stick her arm out and he would put the leather strap around both their arms. Her parents were Holocaust survivors, and during the war her father had looked up to G-d and said, “If you allow me to live, I will honor you every day.” He kept his promise, davening daily, always with a smile. When Evie grew up, she was not particularly religious, attending temple only on the High Holidays. Yet the day she went to prison, she knew she wanted a siddur. She needed to pray.

In 1995, Litwok was arrested for tax evasion and mail fraud. It took 12 years for her case to go to trial. She ended up in prison twice (2009–2011 and 2013–2014) as two counts of her charge were vacated and then retried. She had never imagined herself incarcerated, much less—for seven weeks in 2014—in solitary confinement.

- 3 Comments

May 22, 2017 by Aviva Lauren Lockshin

The Ring Box

I lived most of my life with only one grandparent—my mother’s mother. My other grandparents passed away either before I was born or while I was still too little to have many memories of them. But my grandmother loved me enough for all of them every single day. In my eyes she was pure love, pure giving, the very incarnation of what a devoted Jewish woman should be. We were close. When she passed away at age 93, I was already an adult in my mid-twenties—but that night I cried like a child.

I lived most of my life with only one grandparent—my mother’s mother. My other grandparents passed away either before I was born or while I was still too little to have many memories of them. But my grandmother loved me enough for all of them every single day. In my eyes she was pure love, pure giving, the very incarnation of what a devoted Jewish woman should be. We were close. When she passed away at age 93, I was already an adult in my mid-twenties—but that night I cried like a child.

My grandmother outlived her husband, my grandfather, by over 20 years. She was not always in good health, but she always had a smile for me and said that she was going to live to dance at my wedding. When she died before I had even come close to finding the right guy, I was broken-hearted.

It would be another few years before I met my husband, but when we got engaged it was decided that instead of buying a new ring, I would wear my grandmother’s engagement ring. More than an “heirloom,” as my friends and family called it, the ring was a meaningful connection to the grandmother I had loved and the Jewish womanhood she had modeled for me.

- 1 Comment

May 19, 2017 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Handbag History: How Judith Leiber Came to Create Her Famous Purses

The impetus for Judith Leiber’s game-changing minaudières, exquisite mini-handbags, came not from a carefully thought-out and executed design plan, but from a blooper. Let’s go back to the beginning though: born Judith Peto and raised in Budapest, the fabled handbag designer first studied chemistry in London (to prepare for a career in cosmetics) and then apprenticed at the Hungarian Jewish firm of Pessl, where she learned to cut and mold leather, make patterns, frame and stitch handbags. She was the first woman graduated to master craftswoman, and the first woman to join the Hungarian Handbag Guild in Budapest.

The impetus for Judith Leiber’s game-changing minaudières, exquisite mini-handbags, came not from a carefully thought-out and executed design plan, but from a blooper. Let’s go back to the beginning though: born Judith Peto and raised in Budapest, the fabled handbag designer first studied chemistry in London (to prepare for a career in cosmetics) and then apprenticed at the Hungarian Jewish firm of Pessl, where she learned to cut and mold leather, make patterns, frame and stitch handbags. She was the first woman graduated to master craftswoman, and the first woman to join the Hungarian Handbag Guild in Budapest.

When the Nazis put her country in a chokehold, the company was shut down, but Judith was able to escape the war and, in 1947, moved with her husband, American-born Gerson Leiber, to New York. She soon found work with the fashion house Nettie Rosenstein and rose steadily through the ranks. Mamie Eisenhower wore a Leiber-designed Nettie Rosenstein bag to the presidential inauguration, putting Leiber squarely on the fashion map. After 12 years with Rosenstein, Judith went out on her own, forming Judith Leiber handbags in 1963. She created some 3,500 handbags in such materials as leather, suede, needlepoint, fur and Lucite. But the bags that arguably made her name and her reputation were the jewel-encrusted minaudières that Leiber began making in the late 1960s when an order of gold-plated brass frames arrived damaged; in order to salvage them, she used rhinestones to cover the discoloration. The rest is handbag history, as the current Museum of Art and Design exhibition Judith Leiber: Crafting a New York Story (April 4, 2017 to August 6, 2017) can attest.

- No Comments

May 18, 2017 by Karen B. Winnick

How Animals Teach Us

Creating children’s books about animals has allowed me to express the wonderment I feel when I watch and learn from them.

Creating children’s books about animals has allowed me to express the wonderment I feel when I watch and learn from them.

When I first met Gemina at the Santa Barbara Zoo I knew I wanted to tell her story. Born healthy, the giraffe was three when a bump appeared on her neck. Over time it grew, causing her neck to become severely crooked. Perhaps the bump came from an injury, though the veterinarians would never know for sure. Gemina didn’t allow her disability to prevent her from doing what the other giraffes did. And they accepted her without reservation as part of the herd. Gemina captured the hearts of many visitors.

After my book Gemina, The Crooked-Neck Giraffe was published, I received an email from a young mother in Spain. “When my (four-year-old) son was born, we were told he was deaf. After many tests and surgery, he was implanted with a cochlear implant . . . Every night he wants to see the book. He loves to explain every page. I just want to thank you for writing a wonderful story that is allowing my son to learn new words and teaching about disabilities and how in the eyes of Gemina, we are all the same.”

After my book Gemina, The Crooked-Neck Giraffe was published, I received an email from a young mother in Spain. “When my (four-year-old) son was born, we were told he was deaf. After many tests and surgery, he was implanted with a cochlear implant . . . Every night he wants to see the book. He loves to explain every page. I just want to thank you for writing a wonderful story that is allowing my son to learn new words and teaching about disabilities and how in the eyes of Gemina, we are all the same.”

Animal stories provide gentle ways of helping children feel better. A child with a disability can relate to an animal facing obstacles, one whose determination has helped them to adjust and thrive. Such a story is a boost to a child’s self-image. For a child without a disability a story such as Gemina’s helps to develop sensitivity and compassion for others. For parents there’s an opportunity to open a dialogue.

- No Comments

Feminists In Focus, The Lilith Blog

May 16, 2017 by Yaelle Azagury

Two Films Expose Anti-Sephardi and Anti-Mizrahi Racism in Israel

The New York premier of “The Women’s Balcony” was at the NY Jewish Film Festival in January, and the film was also screened as part of the New York Sephardic Film Festival at the American Sephardi Federation in April. The JCC Manhattan will show the film this Sunday, May 21 and it will officially open in Manhattan on May 26 at the Lincoln Plaza Cinema and The Quad.

Dimona Twist and The Women’s Balcony (both 2016 releases) are two fine new films grappling with the status of Sephardim and Mizrahim in Israeli society. Screened at the New York Sephardic Jewish Film Festival at the American Sephardi Federation in April, they both seek to uncover the obliteration of Oriental Jews in Israel since the creation of the State. Both discredit long-established stereotypes while puncturing the myth of a Jewish homeland equally welcoming to Jews of all ethnic backgrounds.

Michal Aviad’s revelatory Dimona Twist is a documentary focusing specifically on women of Moroccan and Tunisian descent who immigrated to Israel in the 1950s and 1960s. It is the companion piece to The Women Pioneers (2013), which elucidated the trajectory of Jewish women from Eastern Europe to Mandate Palestine in pursuit of a utopian society. In both films, Aviad excels at capturing the experience of immigration from a female perspective. She strikes a pitch-perfect note when speaking of the disillusionment experienced by these women upon arrival at the Promised Land. Her latest documentary also comes in the wake of a new wave of films, such as Kamal Hashkar’s From Tinghir to Jerusalem (2013), that strive to challenge the official Israeli narrative regarding North African Jews, who were often portrayed by Zionist propaganda as victims of Arab enmity in order to encourage them to emigrate to Israel.

- No Comments

May 12, 2017 by Mel Weiss

Two Jewish Moms. One Mischievous Toddler. And Mothers’ Day.

It’s the first year I have to really enjoy the geeky, subtle cognitive dissonance. Last year, when my daughter was still just emerging from the “fourth trimester,” I was too exhausted to think much past diapers. This year, though, with a mischievous toddler who imitates us and giggles with glee, it’s staring me right in the face. The world celebrates Mother’s Day, but in my house, it’s Mothers’ Day.

I trust the cohort of women and others who make up Lilith’s readership to be more than canny enough to catch and appreciate that tiny apostrophic migration, the thing that technically loops me into the equation in the first place. My wife and I don’t really do much for secular holidays—she can never keep track of when they are, anyway—but I feel like for our first real Mothers’ Day, we might have to mark the occasion in some manner. We have a daughter, and she has two moms. Two seriously Jewish mothers.

- No Comments

May 11, 2017 by Chanel Dubofsky

What a Papaya Has to do with Jewish Feminism

One of the first pieces I ever wrote for the Lilith blog, in April 2013, was about how to perform a manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) abortion on a papaya. An MVA is one type of early abortion, and a papaya is a realistic model for a uterus. I wanted to write in order to at least begin to break apart some of the stigma around abortion—in this case that it’s dirty, dangerous, and that doctors who perform it aren’t legitimate. As long as the procedure remains a mystery, the stigma continues to be perpetuated.

One of the first pieces I ever wrote for the Lilith blog, in April 2013, was about how to perform a manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) abortion on a papaya. An MVA is one type of early abortion, and a papaya is a realistic model for a uterus. I wanted to write in order to at least begin to break apart some of the stigma around abortion—in this case that it’s dirty, dangerous, and that doctors who perform it aren’t legitimate. As long as the procedure remains a mystery, the stigma continues to be perpetuated.

When I pitched the piece to the blog’s then editor Sonia Isard, she did not ask, “How is this Jewish?” There was no need to sell an angle, to summon a Jewish connection, because there already was one—Jewish people have abortions. That reality was, and is, enough for an article. The importance was understood, there was no need for proof.

I wrote other pieces after that were less explicitly political—about my mother, her early death, and what that death prevented me from knowing about her, and by extension, about myself. Again, there was no questioning or demand to “make this Jewish.” The strength of an identity does its own work—folding in on, pressing, infusing. How fear is inherited, what we forget, what we mistake, what we’re never told—those are experiences that are universal, but are also certainly impacted by my Jewish imprint.

- No Comments

May 11, 2017 by Sarah M. Seltzer

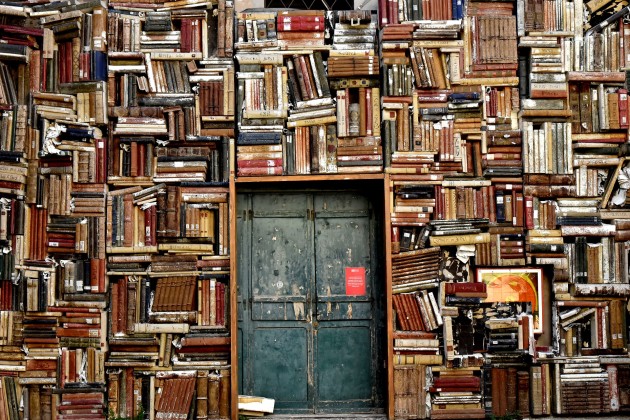

On the Importance of Being Women of the Books

Every day we get further into this madness that is the Trump Administration, the pile of books on my windowsill grows. Never mind that I have no room in my apartment for them, that I had switched to an e-reader several years ago in an effort to keep my shelves from overflowing. All that decluttering effort is officially over. Now I am collecting them like talismans: essays, writers on writing, novels and more novels. As a harried working mom, I have almost no time to read except my commute, but I am slowly making my way through the pile, even as I add to it.

Every day we get further into this madness that is the Trump Administration, the pile of books on my windowsill grows. Never mind that I have no room in my apartment for them, that I had switched to an e-reader several years ago in an effort to keep my shelves from overflowing. All that decluttering effort is officially over. Now I am collecting them like talismans: essays, writers on writing, novels and more novels. As a harried working mom, I have almost no time to read except my commute, but I am slowly making my way through the pile, even as I add to it.

If the apocalypse comes, which it looks like it might, I will be buried in a pile of new releases.

Unlike newspaper articles, tweets, and cable news which agitate us with a certain kind of harsh everyday truth, books allow us to see darkness, but through a softer lens of imaginary experience.

- 1 Comment

May 10, 2017 by Marlena Maduro Baraf

A Mother’s Day Love Letter to My Daughters-in-Law

“The DIL/MIL relationship is a new piece in the universe of connections.”

We begin by sorting and piling up the tiny cardboard pieces. Emily searches with her eagle eye for textures—the folds of fabric in a velvet gown. Brushstrokes. Hair. Kelly looks for like-minded colors; I, for the straight-edge pieces. Daydreaming, one of us will catch sight of a perfect interlocking pair in the chaos of the box. “First One!”

During school break in December, our sons and their families land at our small house in New York. The rooms fill with children’s voices, Lego parts and Barbies. We eat serial breakfasts that last all morning, bake walls and roofs for the gingerbread houses the children will decorate with miniature candy, and manage to subdue any uncomfortable disagreements among the children or adults. Inevitably, someone has brought a 2000-piece puzzle, and during the visit, Emily, Kelly, and I lock ourselves in mind-numbing togetherness at the glass coffee table in my living room.

Emily and Kelly are my DILs. I’m their MIL. I have two daughters-in-law, two sons, and four grandchildren. Until recently I didn’t use the shortcut DILs; I learned this from the young. When Kelly said two years ago only half jokingly, “My MIL would not want that,” I got a surprising hint at the filter through which she was seeing me.

Could it be that the discomfort between in-laws lies in the name? Mother-in-law becomes not-like-mother, mother-once-removed, mother-to-beware-of…. Same for DILs.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...