The Lilith Blog

July 3, 2017 by Avigayil Halpern

End the Anecdotes

It’s becoming a trend for publications to solicit reader stories. The New York Times has recently begun to fill my Facebook news feed with requests for comments from readers. An example: “Tell us a personal story about raising feminist boys, or ask us a question. We may publish a selection of the responses, and some experts in the field will respond to them.” The resulting article featured a selection of the anecdotes the paper received coupled with responses from “some experts in the field.” Early this month, the Forward put out a call on their website, asking “What makes a college perfect for Jewish students?…The Forward wants to hear from you.” The site provides a Google Form with a survey for students, parents, and professionals to fill out, asking respondents to share what was most and least important in their college selection process.

It’s becoming a trend for publications to solicit reader stories. The New York Times has recently begun to fill my Facebook news feed with requests for comments from readers. An example: “Tell us a personal story about raising feminist boys, or ask us a question. We may publish a selection of the responses, and some experts in the field will respond to them.” The resulting article featured a selection of the anecdotes the paper received coupled with responses from “some experts in the field.” Early this month, the Forward put out a call on their website, asking “What makes a college perfect for Jewish students?…The Forward wants to hear from you.” The site provides a Google Form with a survey for students, parents, and professionals to fill out, asking respondents to share what was most and least important in their college selection process.

In a vacuum, it seems innocuous for newspapers to occasionally turn to their readership to gather information about current issues. What better way to learn about feminist parenting or Jewish college choices than to ask feminist parents or Jewish college students to share their stories? These choices by the media are only clearly harmful as they accumulate over time and become increasingly commonplace.

- 2 Comments

June 30, 2017 by Keren McGinity

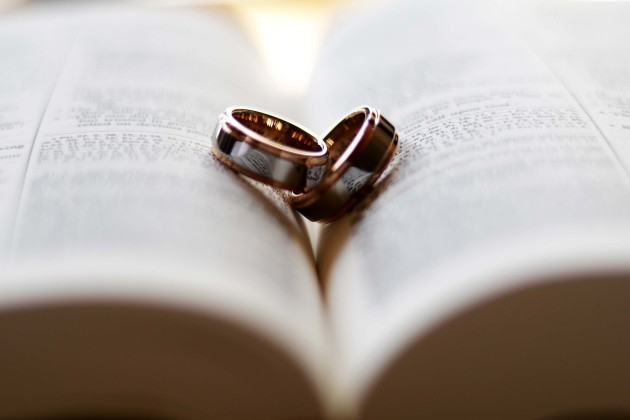

If Jews Are People of the Book, Why Aren’t We Studying Intermarriage?

Jewish sages teach us: “Carve out a time for learning” (Pirke Avot, 1:15). Jews pride themselves on high rates of post-baccalaureate educational achievement, professional degrees, and the associated prestige and success that go with them. Yet when it comes to Jewish intermarriage and interfaith families, we think personal experience or what we read in the Forward is sufficient intel. The uptick in news coverage about intermarriage and officiation at interfaith nuptials in just the past few weeks, the proposal by LabShul’s Rabbi Amichai Lau-Lavie and related rebuttals, including one by the Conservative movement’s Rabbinical Assembly executive vice president Rabbi Julie Schonfeld, tell us that there is a great need in the Jewish community to fully understand this social phenomenon in a deep and meaningful way. But understanding requires education and education is, unfortunately, socially constructed and gendered.

Jewish sages teach us: “Carve out a time for learning” (Pirke Avot, 1:15). Jews pride themselves on high rates of post-baccalaureate educational achievement, professional degrees, and the associated prestige and success that go with them. Yet when it comes to Jewish intermarriage and interfaith families, we think personal experience or what we read in the Forward is sufficient intel. The uptick in news coverage about intermarriage and officiation at interfaith nuptials in just the past few weeks, the proposal by LabShul’s Rabbi Amichai Lau-Lavie and related rebuttals, including one by the Conservative movement’s Rabbinical Assembly executive vice president Rabbi Julie Schonfeld, tell us that there is a great need in the Jewish community to fully understand this social phenomenon in a deep and meaningful way. But understanding requires education and education is, unfortunately, socially constructed and gendered.

The gendering of Jewish education extends to education about intermarriage. Yehuda Kurtzer, president of the Shalom Hartman Institute of North America, asked in a recent Facebook post what people knew or thought about the relationship between the rabbinate and attitudes towards intermarriage, wondering aloud in cyber space why in his estimation “the loudest anti-intermarriage voices are men.” The query netted dozens of responses, many of them insightful about the role of generation, denomination, sexism, power, misogyny, otherness, conversion, and more, which in turn spawned more replies. According to the 2015 survey of Conservative rabbis by Big Tent Judaism (now closed), more female than male rabbis have attended an interfaith wedding, would officiate if the Rabbinical Assembly changed its policy against doing so, and accept patrilineal descent. This survey, while limited to one denomination and those who participated, suggests that men may outnumber women among anti-intermarriage advocates. Although the question about whether there is a gender bias in the rabbinate about intermarriage is worthwhile, more important for the sake of the Jewish future is to look at who is actually educating themselves (mostly women), and to ask: why?

- No Comments

June 29, 2017 by Elena Hoffenberg

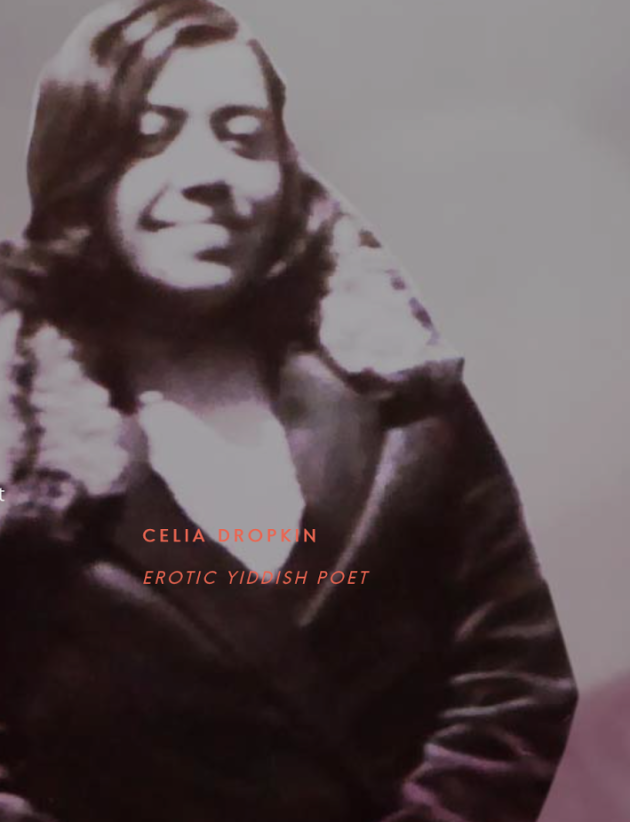

Celia Dropkin: No Mere Yiddishe Mame

Steamy love. Sex. Forbidden affairs. Rebellion. Outrage.

This is what Burning off the Page, a documentary in-the-works by filmmaker Bracha Feldman and director Eli Gorn, promises in examining the work and life of Yiddish poet Celia Dropkin (1887-1956). Born in White Russia, Dropkin studied in Warsaw before immigrating to New York in 1912. She gained a reputation for her ability to capture erotic energy in her poetry through explicit imagery, and also wrote frankly about motherhood and experiencing love and death as a woman. Feldman shows something other than the nostalgic world of Jewish New York by looking into Dropkin’s poetry, and her story.

- No Comments

June 28, 2017 by Chloe Rose Stuart-Ulin

Memorials versus Modern Jewish Life in Poland

In May I visited Treblinka with a small group of Global Leadership fellows. We arrived at the extermination camp in the evening, the only people there, to silence and swarming mosquitos.

In May I visited Treblinka with a small group of Global Leadership fellows. We arrived at the extermination camp in the evening, the only people there, to silence and swarming mosquitos.

Treblinka was a gravel mine before the Nazis took it over in 1940. The pits and mounds of the tunnels are still visible, though now covered by grass. As are the train tracks that transported the gravel away, and then the humans towards. The vast field of grass is ringed with trees and interrupted every so often by enormous, right-angle stones, nearly as tall as a person. They’re jagged and imposing, seemingly placed at random along the path.

Then all at once you turn a corner, the only corner past the trees, and the full scale of the memorial comes into view: 17,000 more stones, standing in clusters, with an eight-meter high monument of flat grey stone at the center. Carved across the top are terrified faces, eyes open, surrounded by other forms left featureless. Above them two hands reach upwards to the sky; a final impression of being buried alive.

In the summer of 2015 I worked full time at a Holocaust Education Centre. I listened to and summarized over 120 hours of recorded witness testimony, gathered from survivors living in Canada. It was my job to find each story’s unique qualities and identify them for possible exhibitions. Polish testimonies were the most horrifying, with the most time dedicated to the camps. I would avoid transcribing them for weeks. It would take me over a year to write about the experience for Lilith’s Spring 2017 issue.

- 2 Comments

June 23, 2017 by Helene Meyers

Flying While Female on El Al

Jewish feminists are celebrating the ruling that El Al airlines can no longer ask women to change seats in order to accommodate Haredi men who believe it is their religious prerogative not to sit next to women. The suit arguing that such religious accommodations are gender discrimination was brought not by a young upstart but rather by an 81 year-old Holocaust survivor, Renee Rabinowitz, with the support of the Reform Movement’s Israel Religious Action Center. According to the Times of Israel, Rabinowitz changed her seat at a flight attendant’s request but the wrongness of the request rankled her.

Jewish feminists are celebrating the ruling that El Al airlines can no longer ask women to change seats in order to accommodate Haredi men who believe it is their religious prerogative not to sit next to women. The suit arguing that such religious accommodations are gender discrimination was brought not by a young upstart but rather by an 81 year-old Holocaust survivor, Renee Rabinowitz, with the support of the Reform Movement’s Israel Religious Action Center. According to the Times of Israel, Rabinowitz changed her seat at a flight attendant’s request but the wrongness of the request rankled her.

Dana Cohen-Lekah, Jerusalem’s Magistrate Court Judge, was unambiguous in her judgment: “Under absolutely no circumstances can a crew member ask a passenger to move from their designated seat because the adjacent passenger doesn’t wasn’t [sic] to sit next to them due to their gender…. The policy is a direct transgression of the law preventing discrimination.” Hopefully, this ruling will end the disruptions and delays that often attend demands for gender-segregated seating.

Renee Rabinowitz’s legal triumph reminded me of the Jewish feminist anguish that I experienced on an El Al flight several years ago.

- No Comments

June 21, 2017 by Eden Gordon

Being Jewish In College. It’s More Complicated Than They Think.

The Forward recently published a survey that asked, “What makes a college ideal for the Jewish student? Is it the presence of pro-Israel clubs? Kosher food options? Jewish fraternities and sororities? Something else altogether?”

The Forward recently published a survey that asked, “What makes a college ideal for the Jewish student? Is it the presence of pro-Israel clubs? Kosher food options? Jewish fraternities and sororities? Something else altogether?”

The question inspired a second glance, and then a more critical investigation. I asked a few of my friends what they feel has been most important to them as Jewish college students. A constant theme in their responses? Pro-Israel clubs, Kosher food options, or fraternities and sororities are not what they cite as defining forces in their religious lives.

I began to think about my own experience. I grew up in a largely Jewish community but for most of my life had put my faith on a back burner. Since coming to college I have become much more spiritual than I was before, finding new solace in the idea of God, but I still have not joined up with many Jewish student groups. I began to wonder—do I count as Jewish without being part of a community? And where do I belong amidst debates about Jewish identity?

I am sure I am not alone in my position on what feels like the fringes of the Jewish community. The only conclusion I can come to is that being the college experience is a complex experience for a Jewish student, one that refuses to yield easy answers. But this space of ambiguity can be a productive one, undoing stereotypes and producing questions that I believe can sometimes be more fruitful than answers.

- No Comments

June 20, 2017 by Nina Pick

Dear Sophie: The Art of Reproduction in the Age of Ecological Catastrophe

“Even the most perfect reproduction … is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.”

“Even the most perfect reproduction … is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.”

—Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”

“The melody of mothers’ speech carries through the bodies and is audible in the womb.”

—Steven Pinker, The Language Instinct

“‘No!’ I said instantly and at once.”

—Imre Kertész, Kaddish for an Unborn Child

Dear Sophie,

Writing prose is like giving birth. The sentence exits the womb reluctantly; it screams as it leaves the body. I’ve never given birth but I can imagine. I’m writing these sentences because I don’t want children. Dear Sophie, this is for you.

Everything about children is repugnant to me. Their shrieking in the park on what would be an otherwise peaceful afternoon. Their wailing on planes where I’m stuck with them thousands of miles in the air and somewhere west of Chicago. Their whining as they trail behind their parents on a beautiful path to the beach. The schmutz of a cookie still lingering on their faces. The pitch of their voices asking their incessant questions. A puddling infant who looks for all intents and purposes like my obese grandfather. I don’t feel what I’m supposed to feel—a sensation in my ovaries, I presume. No joy, no desire, no longing. I feel nothing but a wave of repulsion, and gratitude I’ve made it childless this far.

I thought I’d say this at the outset, so you know where I’m coming from.

However, regardless of this all, I must say that I feel you waiting, as it were, in the wings. Even as I ignore you, rage against you, push you away, you are still there. A deep, still presence, patient, expectant. Sometimes I wonder if I have any say in the matter at all. When you want to enter the world, you will, and I will just be the door you came in by.

Why do you want to live in this world, here in this time and place? By the time you are 30 you may live a daily catastrophe beyond my ability to imagine. You may live on a hot, drought-stricken earth as countries battle over what is left of its water. You may mourn the loss of the last animal species. You may be steeped in a culture so anxious and digitized that the human capacity for empathy, for connection and community, will be as obsolete as the rotary telephone. During your lifespan, even if I train you to live mindfully and simply, you will produce over one hundred tons of trash. It will cost me $200,000 to send you to college, or you will be saddled with a debt you will spend many decades paying. Over the course of your life, you will leave behind a mountain of coffee cups, thousands of plastic bags, hundreds of discarded shoes and jeans and cellphones. You will contribute to the Pacific gyre with your water bottles and toothpaste caps. Your existence will add to child labor, fracking, greenhouse gas emissions, pollution, factory farming, and climate change. As a native speaker of American English, you will write, sing, recite poetry, and make love in the language that is overtaking the world like a virus, endangering cultural and linguistic diversity. Even if I raised you, as I would, to be conscious of your ecologic footprint, to live simply and work for the earth, to eat grassfed beef and grow your own vegetables—even if, in the best case scenario, you grew up to be an artist, a peace activist, a human rights lawyer, a teacher, a homesteader—your very existence would add stress to a much overburdened earth. And that’s the best case scenario. You might vote Republican. You might be a software engineer. You might not care for the earth at all.

- No Comments

June 20, 2017 by Rishe Groner

Embodying the Shabbos Queen

As a little girl, from the age of three, every Friday evening I stood at my mother’s side and would hold her wrist as we lit candles together, waving our arms and circling them three times before reciting the blessing over the Shabbat candles, eyes covered as we silently recited prayers for ourselves, our family, and the entire world. When I would remove my hands from my face, the room would look different. The shabby carpeting a little more lush, the smudged walls more pristine, the tablecloth blindingly white, and the faces of my mother and sister shining like angels.

I’d learned in preschool that this was because of the arrival of the Shabbos queen, the mythical figure that signified the entrance of the Divine presence into our daily lives and the shift from the weekday mundane into Shabbos mode.

- No Comments

June 19, 2017 by Amy Stone

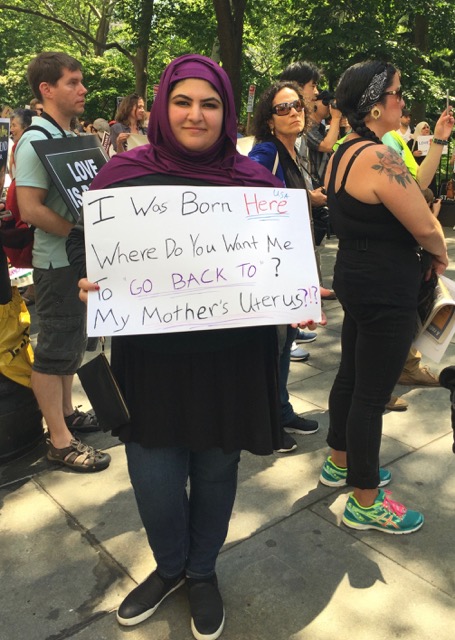

On the Muslim-Jewish Solidarity Trail

What’s a Jew to do?

In the last 24 hours, two brutal attacks on Muslims made the news: on Sunday, the bludgeoning death of 17-year-old Nabra Hassanen after leaving a Virginia mosque with friends; then Monday, a van driven into a crowd leaving a mosque north of London, one man dead at the scene, eight hospitalized. The attacks make calls for Muslim-Jewish solidarity even more compelling.

But just a little over a week ago, I answered the call to action with hesitancy—“NY ♡ Muslims” rally and march Saturday, June 10. A gathering of love in response to the nationwide rallies of Act for America, a Southern Poverty Law Center designated hate group, against sharia law (read “Muslims”).

Photo credit: Amy Stone

First my quibble over the name – “NY ♡ Muslims.” Sounds so condescending. Would anyone say NY ♡ Jews? NY ♡ Women? Beyond that, does a rally reacting to racism only increase the attention?

But I decided to put my body where my mouth is—and show up at the Manhattan rally at City Hall, just a few blocks from the Foley Square court buildings where the Act for America March Against Sharia was taking place.

- No Comments

June 15, 2017 by Eleanor J. Bader

Creating Art for Our “Dire Times”

Dusk, Railroad – 2008 – 30 x 48 – Oil: Canvas

Like many of us, artist Marcia Annenberg is worried. First, there’s climate change. Then there’s the growing erosion of U.S. democracy—including the loss of many long-held civil liberties—and the tendency of mainstream media to replace hard news with entertainment and fluff.

“We’re in dire times,” the Manhattan-based Annenberg begins. “It’s frightening. The only consolation is that the American system of government was developed to protect us from efforts to subvert our institutions in negative ways.”

Annenberg’s work—color-driven abstracts and installations and paintings meant to jolt the viewer’s political awareness—are in numerous permanent collections: The London Jewish Museum; the Vad Yashem Art Museum in Jerusalem; the Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum in Lithuania; and the Florida Holocaust Museum, among them. In New York City, she is represented by the Flomenhaft Gallery, one of Chelsea’s most respected women-owned exhibition spaces.

Annenberg sat down with Eleanor J. Bader on a blisteringly hot June morning. Surprisingly, despite the heavy subject matter, the pair found a great deal to laugh about as they discussed what it means to call oneself a progressive, humanist, activist-artist at this particular moment.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...