The Lilith Blog

August 9, 2017 by Patricia Grossman

Q&A with Author of “The Lost Letter”

Jillian Cantor’s new novel, The Lost Letter, alternates between two very different protagonists and settings. In 1938 Austria, young Kristoff is apprenticed to a master stamp engraver, while in Los Angeles in 1989 a journalist, Katie Nelson, is in the process of getting a divorce and working out new ways of relating to her father, who has Alzheimer’s and now lives at The Willows.

Jillian Cantor’s new novel, The Lost Letter, alternates between two very different protagonists and settings. In 1938 Austria, young Kristoff is apprenticed to a master stamp engraver, while in Los Angeles in 1989 a journalist, Katie Nelson, is in the process of getting a divorce and working out new ways of relating to her father, who has Alzheimer’s and now lives at The Willows.

As radically different as these characters’ experiences are on the surface, the novel slowly discloses that they are in fact inexorably linked.

Q. Your last novel, The Hours Count, featured Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Did you encounter historical models for your characters as part in your research for The Lost Letter?

Kristoff and the Fabers are completely fictional, but I did find stories about real engravers in Europe who came to work with the resistance and forge papers, as Kristoff eventually does. I also found different real ways stamps were used in the resistance throughout the war. For example, the British special ops forged stamps by replacing Hitler’s head with Himmler’s, hoping to cause infighting in the regime, but then they put them into circulation and no one noticed! The stamps and resistance efforts in my novel are fiction, but it did all start for me with the idea that real stamps were used in the real resistance.

Q. Stamps of a certain time and place serve beautifully to pull the various threads of The Lost Letter together. Were you certain from the beginning of the novel that you wanted to use stamps—and one particular stamp—as a pivot for your story?

The idea for the novel started with stamps, so I was certain about that much from the beginning. I was chatting with my agent one day about what I was going to write next, and she asked me if I’d ever thought about the people who illustrate postage stamps. (I hadn’t before then!) I began to do a little research about stamp engravers, stamps in WWII, and stamp collecting, and the story blossomed from there. The idea that it would be about one particular stamp came a bit later, as I was writing the first draft and plotting out the novel.

- No Comments

August 8, 2017 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

One Jewish Mother’s Account of the Prison Industrial Complex

The call, when it came, was more of a puzzle than an alarm. I had wandered downstairs on a lazy Sunday morning in July to find a message on the machine: an automated operator from the Legacy service announcing that there was a collect call from—and here the voice switched to that of my then-21-year old son—and I could press one to accept or two to deny. I’d been asleep when the call came in so accepting was a moot point. Besides, why was my son calling collect? He’d gone out the night before with both cash and his American Express credit cards.

The call, when it came, was more of a puzzle than an alarm. I had wandered downstairs on a lazy Sunday morning in July to find a message on the machine: an automated operator from the Legacy service announcing that there was a collect call from—and here the voice switched to that of my then-21-year old son—and I could press one to accept or two to deny. I’d been asleep when the call came in so accepting was a moot point. Besides, why was my son calling collect? He’d gone out the night before with both cash and his American Express credit cards.

I checked his room; he wasn’t in it, but I was still not alarmed. He’d probably decided to stay in the city. But as eleven inched toward noon, I began to feel some concern. I phoned him—no answer—and then started going down a list of friends. During this time, I received two more collect calls, both courtesy of the Legacy phone service; this time, I anxiously pressed one to accept, but as soon as I did the line went dead. When I first Googled and then called Legacy, a customer service rep said, “Ma’am, that call is coming from a jail; you have to have set up a credit card account with us in order to accept.” My first thought was, Jewish boys don’t get put in jail. Then the panic exploded, a fireball in my chest.

- 2 Comments

August 7, 2017 by Rishe Groner

Why Tu B’Av Is Much More Than Just “Jewish Valentine’s Day”

When I was in elementary school, our Australian Jewish private school had a strict uniform, down to accessories: only navy blue knee-high socks or tights, and navy or royal blue hair bows or scrunchies. (It was 1993). Once a year, though, I remember that my sister and I whipped out the white frou frou barrettes we’d worn at our aunt’s wedding, and donned the white knee-high socks we wore on weekends. We’d get to school and there’d be Israeli dancing in the assembly area, following the steps announced by a heavily accented teacher. It was Tu B’Av, the date on the Hebrew calendar worth remembering and celebrating zestfully. With our white clothing and our dancing, we were almost, if not quite, imitating the traditions of our ancestors.

When I was in elementary school, our Australian Jewish private school had a strict uniform, down to accessories: only navy blue knee-high socks or tights, and navy or royal blue hair bows or scrunchies. (It was 1993). Once a year, though, I remember that my sister and I whipped out the white frou frou barrettes we’d worn at our aunt’s wedding, and donned the white knee-high socks we wore on weekends. We’d get to school and there’d be Israeli dancing in the assembly area, following the steps announced by a heavily accented teacher. It was Tu B’Av, the date on the Hebrew calendar worth remembering and celebrating zestfully. With our white clothing and our dancing, we were almost, if not quite, imitating the traditions of our ancestors.

Ancestors—aka the ladies of Shiloh. The maidens of ancient Israel and Judea who each year at the grape harvest would celebrate ecstatically with dances through the vineyards and onto the wine press. As they squeezed the grapes with their bare feet, they drew the glances of young men who came to the annual festival to find their chosen wives. And with it, the most unusual mating ritual until The Bachelorette. Maidens garbed themselves in white dresses, perhaps imagining themselves as Anne Shirley’s “heroine in a white muslin dress,” looking their best for their gentlemen suitors––but with a catch. No woman wore clothing that was her own. The poorest maiden wore elaborate dresses from her rich neighbors, while the daughter of the mayor borrowed a simple shift from an acquaintance. The maidens would call out across the fields at the gentlemen spectators, shouting out their traits as if in a cattle market.

“Look not to riches, for a woman with pious deeds is worth more than rubies!” The daughter of the baker would shout.

“Worry not about the beauty of your wife, for far more important is her family and illustrious ancestors!” The daughter of the Torah scholar who did not meet conventional beauty standards might announce.

Each woman would find ways to showcase the value of her particular brand of beauty—while, the Talmud tells us, criticizing the conventional modes of beauty that might be priorities for others.

- No Comments

August 3, 2017 by Rebecca Mordechai

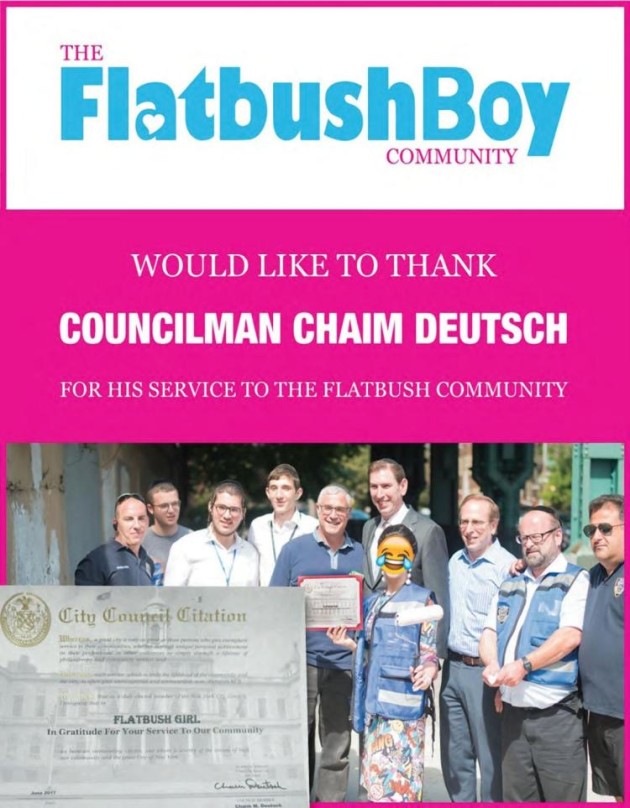

An Emoji Worth a Thousand Words: One Orthodox Woman Uses Humor to Become Visible

Flatbush Jewish Journal

When Hillary Clinton’s face was covered by the image of a hand in a 2016 copy of an Orthodox newspaper, I choked on my coffee. In the age of ‘woke’ and social activism, concealing the former presidential candidate, in all her strength and pant-suited glory, seemed downright bizarre. I immediately took to Facebook to lambast the ridiculousness of this photo. “Gloria Steinem would be so proud I tell ya,” I posted, earning just one like and one comment.

Unlike me, Adina Miles, an Orthodox 29-year-old mother of two, has the pluck and the platform to get hundreds of people talking about how absurd it is to conceal women’s faces in conservative Jewish publications.

It all started when Miles created @FlatbushGirl, an Instagram account documenting the everyday life of an Orthodox woman—comedic mishaps when baking challah, and shopping for jewelry with an opinionated mother-in-law. After posting several clever and relatable videos for the Orthodox community, Miles’s account swiftly accumulated thousands of followers. Miles then decided to leverage her newfound public persona to create a cleaner environment in Flatbush, the epicenter of Brooklyn’s Orthodox community. She partnered with Councilman Chaim Deutsch of Brooklyn to paint over local graffiti, and posed near him (and other community activists) in a photo for the Flatbush Jewish Journal (FJJ).

- 1 Comment

August 2, 2017 by Eleanor J. Bader

Meet Bryna Wasserman: The Award-Winning Director Revitalizing Yiddish Theatre

Photo credit: Joan Roth

When award-winning theatre director Bryna Wasserman—her accolades include the 2000 Montreal English Critics Circle Award of Distinction, the 2010 Mlotek Prize for Yiddish and Yiddish Culture, and the 2011 Quebec Drama Federation Award “in recognition of immense contributions to and support of the development of theatre in Quebec”— took the helm of the New York City-based National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene (NYTF) in 2011, she had three goals.

The first was to find NYTF a permanent home. “We’d been wandering Jews for a century, going from one theatre to another,” she says. “There was an urgent need to change this.” The second goal was financial: to put the non-profit NYTF on solid footing. Lastly, she wanted the company’s 2015 centennial to foster a contemporary appreciation of Yiddishkeit.

All of this, of course, had to be done while making sure that the theatre staged at least one annual production and brought performances to diverse communities throughout, and beyond, the five boroughs of New York City.

Wasserman sat down with Eleanor J. Bader to discuss the overall state of Yiddish theatre and the ups-and-downs of running the NYTF. Along the way, the conversation touched on the plight of immigrants under Trump and the challenges facing all non-profit theatres.

- No Comments

August 1, 2017 by Rishe Groner

How Reading the Prophets Through a Feminine Lens Illuminates Tisha B’Av

This week’s period of mourning on the Jewish calendar, and today’s day of mourning, Tisha B’Av, vary in their significance for those living in the sometimes-comfortable sometimes-challenging diaspora. Some view the holiday as an irrelevant memorial to an Ancient temple, others as a current remembrance of the roots of tragedy throughout both society in general and our ancestors and people in particular.

Lamentations is traditionally read on the Ninth of Av, and Isaiah and Jeremiah are also both read around this time in the Jewish calendar. In these texts, there is no shortage of imagery surrounding the many iterations of the weeping woman—Mother Rachel, the Mother of Zion, and the daughter of Zion. She is wearing tattered clothing. She is abandoned as a whoring woman by her fickle lovers. She is weeping as her children starve and lick the dust. She is primal in her crazed pursuit of survival. She is destroyed as she wails on a mountaintop, a black-clad banshee.

The divine mother is not a frequent image in modern day Judaism, and the divine daughter even less so. But it’s in this space of deep exile surrounding Tisha B’Av, when the people have lost all hope and identity, that we see her imagery ring out.

- No Comments

July 28, 2017 by Helene Meyers

The Misogyny of Menashe

At the preview of Menashe at the Manhattan JCC last Thursday, director Joshua Weinstein expressed his tongue-in-cheek hope that the title character, a Hasidic widower who wants to raise his son without remarrying, will become the second most famous Jew today (the first, of course, being Ivanka Trump). Already reviews of the film are lauding the universality found in the particular. As a lover and critic of Jewish American cinema, I eagerly anticipated Menashe. A U.S. made Yiddish-language film—how much more Jewy can we get? But after watching the film, I couldn’t shake the feeling that what is being presented as universality is really old time misogyny.

At the preview of Menashe at the Manhattan JCC last Thursday, director Joshua Weinstein expressed his tongue-in-cheek hope that the title character, a Hasidic widower who wants to raise his son without remarrying, will become the second most famous Jew today (the first, of course, being Ivanka Trump). Already reviews of the film are lauding the universality found in the particular. As a lover and critic of Jewish American cinema, I eagerly anticipated Menashe. A U.S. made Yiddish-language film—how much more Jewy can we get? But after watching the film, I couldn’t shake the feeling that what is being presented as universality is really old time misogyny.

At the JCC screening, Weinstein was asked about the representation of women in the film. Although he seemingly welcomed the question, he also got a tad bit defensive. Indicating that this was “the biggest debate” in making the film, he ultimately responded that this film was “not about a woman but a widower.” Fair enough, but there ARE women on the margins of the film and most of them are cast in unflattering, stereotypical roles. Menashe’s sister-in-law, who is raising Menashe’s son, is notable only for her “bad” and unimaginative cooking. A female shopper in the store at which Menashe works is obviously burdened by her large brood of children in sharp contrast to Menashe who is desperate to keep his son and who piously considers a large family a blessing. Menashe’s wife was not particularly fruitful—she bore him only one son. Notably, he expresses relief (albeit with respectable attendant guilt) that his wife died of a blood clot after undergoing in-vitro fertilization.

Yet, when Menashe pursues a potential marriage partner so that he can regain his son, she is cast as unfeeling for being ready to be married again after only four months of widowhood. She also expresses disdain for a rabbi who advocates driving for women, suggesting that women are the real policewomen of patriarchy (to be fair, we have a VERY quick scene of one of Menashe’s nieces in the background arguing that the Ruv—Yiddish for rabbi—can’t stop her from attending college). Some might argue that Weinstein’s commitments to neo-realism compel this gender trouble; after all, the film is based on the life of Menashe Lustig, the non-professional Hasidic actor who plays the title role. However, even neo-realistically inclined directors (Weinstein is a documentarian) make choices. For me, the most telling and disturbing scene is one in which Menashe bonds with Hispanic workers complaining about their wives. Welcome to the Trump era in which the universal appeal made to a larger audience is a coalition of Hasids and Hispanics doing a version of Henny Youngman’s “take my wife, please take my wife” routine.

- 2 Comments

July 27, 2017 by Danica Davidson

Breaking the Taboo: Women Who Regret Motherhood

Orna Donath, an Israeli sociologist, anthropologist and author of Making a Choice: Being Childfree in Israel, has come out with a new study titled Regretting Motherhood. Applying a feminist lens, it interviews Jewish Israeli women who, as the title indicates, regret becoming mothers and discuss the ramifications of their regrets. Donath shows the difference between not wanting to be a mother and not liking children; the women in the study often talk about their love for their children and what they do for the sake of the children’s well-being, while saying that if they could go back in time, they would not want to be mothers. This groundbreaking study tackles a rarely discussed subject, often left unmentioned because of obvious taboos. Donath told Lilith why she decided to write about this aspect of women’s reproductive rights, the stigma around women who don’t want to be mothers, and how she sees the possibility of a positive paradigm shift.

Danica Davidson: Before Regretting Motherhood, you were already writing about reproductive rights and deciding not to be a mother. Why did you decide to write a book from this angle?

Orna Donath: At the end of my first study (it was conducted between 2003-2007 about Israeli-Jewish women and men who do not want to be parents), I was left with one sentence that kept troubling me and that is the certain promise towards women mostly: “You will regret it. You will regret not being a mother.” It was hard for me to leave it at the dichotomous determination that decisively pins regret to being a non-mother by threatening women with regret as a weapon, while at the same time simply excluding any possibility to think of regret following motherhood.

Since I was sure that there are women who regret becoming mothers, I decided then to write my Ph.D. about it (which later on turned out to be the book Regretting Motherhood). I didn’t want to learn about regretting motherhood “only,” but to study the relationship between society and emotions, and the political usage of them as well.

- 1 Comment

July 26, 2017 by Haley Kossek

Dear Chelsea Clinton: Clara Lemlich was a Communist—and a Jew

Clara Lemlich c. 1910

This summer, former first daughter Chelsea Clinton released her new children’s book, She Persisted: 13 American Women Who Changed the World. In it, she profiles, among others, the Jewish labor organizer and Communist Party activist Clara Lemlich with these words: “After her family fled poverty and the threat of violence in Ukraine for a new home in New York City, Clara Lemlich got a new job working in a garment factory. She wrote that the factory’s conditions made women into machines, and so she persisted, organizing picket lines and strikes that ultimately helped win better pay, shorter hours, and safer working conditions for thousands of workers—both women and men.”

I wrote this open letter in response.

Dear Chelsea Clinton,

I write to inform you that Clara Lemlich—leader of the Uprising of 20,000 garment workers in 1909, queen of my heart, featured in your new children’s book—was a Communist and a Jew.

She did not flee generic “poverty and the threat of violence in Ukraine,” as you write; she fled an anti-Semitic pogrom in which 47 Jews were killed, 592 were injured, and 700 Jewish families’ homes were destroyed. Later Clara would become a union leader of thousands of immigrant Jewish factory girls in New York City whose lives and work experiences were intimately defined by the same anti-Semitic violence that she had survived. Her famous speech rousing those young women to strike, quoted in your book, was delivered in Yiddish, not English. Little girls reading your book deserve to know this history, which you neglect to mention: Clara Lemlich was a Jew.

- 37 Comments

July 25, 2017 by Tamara Miller

The Rabbi in the ER

To enter the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., you must first be screened by security.

The entryway is darker than that of many museums. To the right begins the journey through the hallowed spaces of history. But one important piece of history hangs on the wall in the entryway. It is a large photo of a young man in a uniform. The plaque beneath it reads:

While protecting visitors and colleagues, Special Police Officer Stephen Tyrone Johns was fatally shot on June 10, 2009, by an avowed anti-Semite, Holocaust denier, and racist. Officer Johns’s outgoing personality and generous spirit endeared him to all who entered this museum, which was created to confront the very hate that took his life. His sacrifice shall never be forgotten.

I was the Director of Spiritual Care at George Washington University Hospital when Stephen Tyrone Johns was brought into the emergency room. His life would end that day, and mine would never be the same.

- 1 Comment

Please wait...

Please wait...