The Lilith Blog

November 7, 2017 by Chanel Dubofsky

We Need To Talk About Sexual Harassment in Tip-Based Jobs

When H was 23, she worked as a server at a restaurant known for its brunch menu. One morning, she told me, she was in the kitchen making coffee with another employee who was prepping eggs. “He was maybe—ten feet away from me,” she said. H asked him how his weekend had gone, and in response, “he crossed the room, kissed me, and then went back to his spot and answered my question.”

When H was 23, she worked as a server at a restaurant known for its brunch menu. One morning, she told me, she was in the kitchen making coffee with another employee who was prepping eggs. “He was maybe—ten feet away from me,” she said. H asked him how his weekend had gone, and in response, “he crossed the room, kissed me, and then went back to his spot and answered my question.”

She mentioned the incident to a male server, who dismissed it, but later, the man who kissed her was fired, after harassing and assaulting other female members of the staff. “It didn’t occur to me to mention it to anyone higher up,” H said. “I thought it was the kind of thing you just have to deal with.”

If you’ve ever worked in food service, like a restaurant or a coffee shop, you know that much of your time and energy are spent trying to get good tips, which, if you’re a server, make up the bulk of your take-home pay. People eating in restaurants might not know this, but the U.S. federal minimum wage for tipped employees is $2.13 an hour. “You’re not making anything if you’re not getting tips, said H. “So if you’re going to do something that jeopardizes your tip, it had better be worth it.”

- No Comments

November 6, 2017 by Rachel Brustein

Dear Reform Movement, Israeli Feminism Isn’t Enough

“NFTY takes a stand on controversial issues,” declared a rabbi and staff member at the time to a room of a thousand high schoolers and Jewish professionals at NFTY (North American Federation of Temple Youth) Convention 2011. The room erupted in cheers and applause. In that moment, I felt proud to be part of a movement that took a stance on such issues. I still feel proud of the education and advocacy NFTY does on domestic issues in the United States. However, I wish I knew then what I know now—that NFTY was not speaking about the occupation in Israel-Palestine.

- 1 Comment

November 3, 2017 by Joan Roth

Photographer’s Journal: Looking Back on the Women’s Convention in Detroit

Tamika Mallory, co-president of the Women’s March Board, speaking at the opening session, “Reclaiming Our Time: Setting the Agenda Together.”

Actress Rose McGowan (left) and Tarana Burke (right) who founded #metoo ten years ago, standing together at opening session of the Women’s Convention.

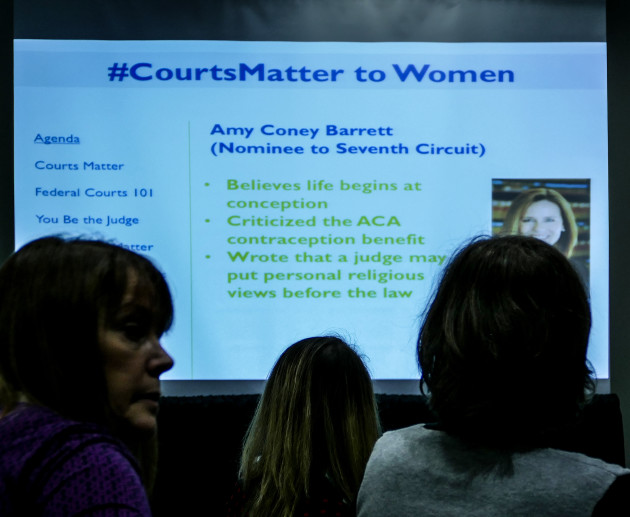

The National Council of Jewish Women (NCJW) ran a session on the importance of the courts to women at the convention.

Emily Jane Steinberg took people’s words and creatively placed them on paper.

Cobo Hall was where the welcome reception “Art of the Resistance” was held. It also contained the Woman’s Market, an art gallery, social justice city, and Oxfam refugee road.

- No Comments

November 1, 2017 by Tirzah Goldenberg

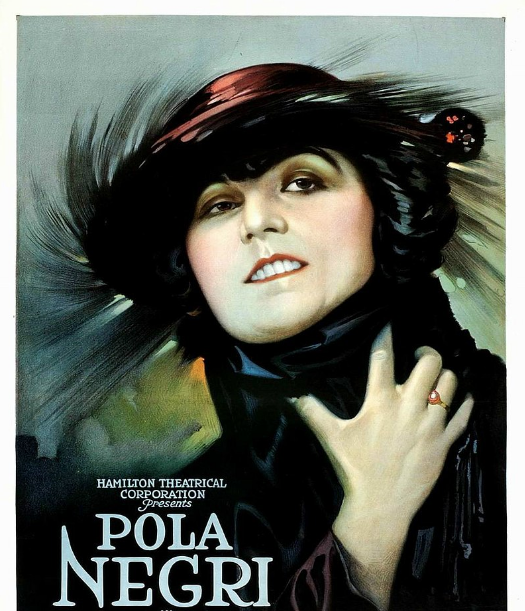

Saved From the Nazis: A Silent Film About a Lost Jewish Woman

Most silent films have been lost due to neglect, improper archival storage, the spontaneous combustion of their highly flammable material, or intentional destruction once the era of sound films would deem the discrete and time-bound “genre” irrelevant and obsolete. Der Gelbe Schein, translated as The Yellow Ticket, a 1918 silent movie set in both St. Petersburg and the Polish town of Sokolowice, was thought to be lost for a different reason—because the Nazis wanted all traces of Jewish culture gone and had allegedly destroyed all surviving copies of this progressive film about Jewish identity and anti-Semitism in Russia. Its leading actress, Pola Negri, wrote of the film in her autobiography, “Its sympathetic portrait of Jews… might even help to spread a little tolerance and understanding.”

Most silent films have been lost due to neglect, improper archival storage, the spontaneous combustion of their highly flammable material, or intentional destruction once the era of sound films would deem the discrete and time-bound “genre” irrelevant and obsolete. Der Gelbe Schein, translated as The Yellow Ticket, a 1918 silent movie set in both St. Petersburg and the Polish town of Sokolowice, was thought to be lost for a different reason—because the Nazis wanted all traces of Jewish culture gone and had allegedly destroyed all surviving copies of this progressive film about Jewish identity and anti-Semitism in Russia. Its leading actress, Pola Negri, wrote of the film in her autobiography, “Its sympathetic portrait of Jews… might even help to spread a little tolerance and understanding.”

But The Yellow Ticket survived any attempt to destroy it. The film was discovered in a private collection in Holland and now has been digitally restored. The preservation is not without its hints at deterioration—an occasional flickering that plays over the images, reminding us of their impermanence.

- No Comments

November 1, 2017 by Amy Stone

This Director Got Death Threats. Her Work Will Open the Other Israel Film Festival Tomorrow.

What better film to open the New York JCC’s Other Israel Film Festival than “In Between” – the first feature by a 35-year-old Palestinian woman, with scenes triggering death threats and a fatwa.

What better film to open the New York JCC’s Other Israel Film Festival than “In Between” – the first feature by a 35-year-old Palestinian woman, with scenes triggering death threats and a fatwa.

With the slogan “Film. Change. Action,” the 11th Annual OIFF opens at the JCC Manhattan tomorrow evening (Nov. 2). Director Maysaloun Hamoud will appear in conversation with other filmmakers after the screening. (“In Between” has already won numerous international film festival awards and opens commercially in the U.S. in January.)

- No Comments

October 31, 2017 by Rebecca Mordechai

No Halloween Ghoul Can Compare to the Fear That This Jewish Ritual Inspires

Halloween superstitions (cue black felines stretching taut bodies on still roads) reign in the dusks of October. But the ghost of my former Orthodox self is hardly affected by these scares. Jack-o-Lanterns and Dracula costumes remind me only of America’s perpetual urge to capitalize on basic human instincts (in this case, of course, fear). They are child’s play compared to the one superstition that haunted me most: the Evil Eye.

Halloween superstitions (cue black felines stretching taut bodies on still roads) reign in the dusks of October. But the ghost of my former Orthodox self is hardly affected by these scares. Jack-o-Lanterns and Dracula costumes remind me only of America’s perpetual urge to capitalize on basic human instincts (in this case, of course, fear). They are child’s play compared to the one superstition that haunted me most: the Evil Eye.

Yes. The Evil Eye, or as it is known in Hebrew, the ayin hara.

Ayin hara is the gaze born of envy. This gaze can do more than merely make its victim feel uncomfortable. It can be the origin of the victim’s sudden bout of sickness, misery, and even death. The Torah mentions ayin hara and states that the only group protected from its possible calamity are the descendents of the biblical hero, Joseph.

Over afternoon Shabbos teas and communal challah bakes, women have been peppering their conversations with “bli ayin hara” (“without an ayin hara”) for generations: “Mrs. Schwartz has seven children, bli ayin hara” or, in Yiddish, “My father is 80 years old, kayn ayn hora.” These three words continue to be a verbal amulet against anyone who may be jealous of another’s progeny or long life.

***

My family emigrated from Baku, Azerbaijan to the States in 1989. While Azerbaijan’s main religion is Islam, it’s also important to note to that many Romani groups live in the country. Not surprisingly, Islamic and Romani rituals against the Evil Eye have all combined to heighten my culture’s terror of the ayin hara. Since I was a child, I could barely keep count of how many times my swarm of relatives let the words “ayin hara” tumble out of their lips with a dread that rivaled words like “cancer.”

My mother coaxes:

“Be careful, Rebecca. That dress shows off your figure. Don’t wear it, you may get an ayin hara.”

“Don’t participate too much in class, Rebecca. Your friends may be jealous of your smarts and give you an ayin hara.”

Or she laments in hushed tones:

“My handsome and successful son is not married yet because he got an ayin hara when he was younger.”

“Your father’s brother passed away when he was a child because someone gave him an ayin hara.”

And then, the panic:

“We may get sick because of ayin hara! We may lose our money because of ayin hara! We may die because of ayin hara!”

Madonna made the red string (believed to ward off the Evil Eye) Kabbalah-chic, leading self-proclaimed bohemians and yoga instructors to tout them on wrists and ankles. But, according to Azerbaijan’s Jewish lore, salt sprinkled over one’s head and then burned is the true antidote against ayin haras. If I ever broke out in a raging fever, received an unexpected slew of bad grades, or waddled in a stage of adolescent loneliness, my mother would usher me to her side with salt in her palm.

“Those who gave you the Evil Eye should be destroyed like this salt will be destroyed,” she proclaimed.

There was palpable fierceness to her words, to her motions, and to her eyes.

“Mom’s like a witch,” my brother looked on and laughed.

I was not laughing. Instead, I watched the salt burn beneath the eager blaze.

***

As a thirteen year old, making sense of cruel social cliques, my sudden rebellious body, and increasingly difficult math problems to solve, I felt close to powerless. I needed something raw and forceful to blame for the misfortunes that teenagehood inflicts. And so, immersed in a culture that enclosed me in its walls of superstition, I quickly became obsessed with the Evil Eye.

First, there was the paranoia. Paranoia that my friends, teachers, and even my own family, were blasting ayin haras my way. As I turned my back, I imagined their eyes, like caricatures of every demon-possessed child in horror movies, shot Arctic rays of envy through my spine: I will fail my next test because of them. I will have no friends because of them. I will grow to be ugly because of them.

Second, were the chants. With a mouth moving fast in worry, I murmured the following under my breath every time I felt like I was the recipient of the Evil Eye (which was, on average, five times a day): “May the Evil Eye that (blank) is giving me be completely destroyed.” I chanted this personalized prayer ten times in a row. It must be said ten times, otherwise I would amount to tepid nothingness. Five Evil Eyes + ten chants per Evil Eye equals to 50 chants per day.

Third, was the insomnia. Insomnia was the Rosemary’s baby that my paranoia and excessive chanting conceived. It taunted me every night in middle school. My hands were unsteady as I lifted a glass of caffeinated tea in the morning, and I arrived to class with knotty hair and cartoonishly large eye bags.

Fear of the Evil Eye, and its consequences, chased me from middle school to high school. This fear was only murdered when l was finally driven away from the rituals of a cloistered lifestyle in college. By then, I had become not only emotionally exhausted from years of superstitious beliefs, but also from religion itself. Both superstition and my ultra-Orthodox upbringing have been charged, mercilessly, with fear and paranoia. The synapses that were responsible for firing thoughts like “If I wear my new dress, I’ll get an Evil Eye” also fired thoughts like “If I don’t dress modestly, God will punish me.” Rumination bred obsession which bred anxiety which bred meaninglessness. And meaningless is the antithesis of what religion is proud to brag to its disciples.

On this Halloween, as its nostalgic reruns of Hocus Pocus and a new season of Stranger Things entertain millions, I know that I will dwell on my past hauntings.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.

- No Comments

October 31, 2017 by Naomi Danis

My Post-Holocaust American Halloween

My mom was a European-born Holocaust survivor, and trick-or-treating was out of the question for her children when my sisters and I were growing up in the late 1950s and early 60s. Halloween, to her, was based on some saint’s holiday twisted into an occasion for anti-Semitic pranks and graffiti. Some of our Jewish day school classmates were allowed to knock on doors collecting money for Unicef, as an acceptable Jewish alternative, transforming the holiday into an occasion for tzedaka, but this too was forbidden us. Of course some of our classmates were from families we thought permissive, and observed Halloween in full regalia, as an American holiday, though I don’t think they felt comfortable bragging about it in school. We were told we had Purim, a superior holiday, because it was an occasion for dressing up, but also for giving shalach manot, rather than taking things from people.

My mom was a European-born Holocaust survivor, and trick-or-treating was out of the question for her children when my sisters and I were growing up in the late 1950s and early 60s. Halloween, to her, was based on some saint’s holiday twisted into an occasion for anti-Semitic pranks and graffiti. Some of our Jewish day school classmates were allowed to knock on doors collecting money for Unicef, as an acceptable Jewish alternative, transforming the holiday into an occasion for tzedaka, but this too was forbidden us. Of course some of our classmates were from families we thought permissive, and observed Halloween in full regalia, as an American holiday, though I don’t think they felt comfortable bragging about it in school. We were told we had Purim, a superior holiday, because it was an occasion for dressing up, but also for giving shalach manot, rather than taking things from people.

- No Comments

October 31, 2017 by Susan Weidman Schneider

My Jewish, Canadian Halloween

Underneath the pirate costume, dug out of the attic, I’m in my brown snowsuit, hood, mittens and all. In the already dusky-dark late afternoon I walk with my grownup (my mother? my Zayde? my much-older brother?) through the snowy air and around the corner to a few nearby neighbors, Jews and non-Jews. I shout gleefully from each front path, “Hallow-een A-pples” at the top of my four-year-old lungs. (The chant’s irresistible combo of anapest and that assertive iamb is so compelling that I can still holler it pretty authentically even now.)

Underneath the pirate costume, dug out of the attic, I’m in my brown snowsuit, hood, mittens and all. In the already dusky-dark late afternoon I walk with my grownup (my mother? my Zayde? my much-older brother?) through the snowy air and around the corner to a few nearby neighbors, Jews and non-Jews. I shout gleefully from each front path, “Hallow-een A-pples” at the top of my four-year-old lungs. (The chant’s irresistible combo of anapest and that assertive iamb is so compelling that I can still holler it pretty authentically even now.)

By October, evening sets in very early in Winnipeg, and what stays with me is the season’s imprint. Instead of looming ghosts and goblins, Halloween and its early dark—and the possibility of snow—plus the adventure of being out in the crisp air, felt very gentle. Growing up, not a single household I knew celebrated what’s now called “Canadian Thanksgiving” (usually the same weekend as Columbus Day in the U.S.), so Halloween is my cool-weather holiday of record.

- No Comments

October 30, 2017 by Amelia Dornbush

What Reading Heschel Taught Me About My Childhood Halloween

People often assume that since I didn’t spend the first 13 years of my life growing up Jewish (it’s a long story), I must have been raised Christian. This isn’t really true.

People often assume that since I didn’t spend the first 13 years of my life growing up Jewish (it’s a long story), I must have been raised Christian. This isn’t really true.

“What were you before you were Jewish?”

“Nothing?”

“What do you mean nothing?”

“I don’t know, nothing. We just, didn’t do religion.”

By the time I was 13, I had set foot in synagogue more times than I had in a church. Sure, we did celebrate Christmas—just without Christ or Mass. We had tried doing some Humanist something-something when I was little, but that was a flop. I had neither baptism nor brit habat, neither bat mitzvah nor confirmation. Until my parents converted to Judaism, religion just wasn’t a thing in my life.

This meant the number of holidays I could really sink my teeth into without the complication of God was extremely limited.

Halloween, though, was among them.

- No Comments

October 30, 2017 by Joan Roth

Photographer’s Journal: Shabbat at the Women’s Convention in Detroit

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.

- 2 Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...