The Lilith Blog

December 26, 2017 by Eleanor J. Bader

Meet the Jewish Lesbian Feminist Who Goes Undercover to Report on the Alt-Right

When award-winning journalist Donna Minkowitz (author of Ferocious Romance: What My Encounters with the Right Taught Me about Sex, God and Fury and Growing up Golem: How I Survived My Mother, Brooklyn and Some Really Bad Dates) attended a conference sponsored by the innocuously-named American Renaissance organization last summer, she knew she would be rubbing elbows with leaders of the alt-right. The three-day confab, held a few weeks before the Charlottesville Unite the Right rally, took place in a Tennessee state park and drew approximately 300 people, 90 percent of them male and all of them white.

Minkowitz, a self-described “secular, Jewish, lesbian feminist and leftist,” told Eleanor J. Bader about covering the event for Political Research Associates, an independently-funded social justice think tank based in Somerville, Massachusetts. She also spoke about her earlier interactions with conservative organizations.

- 3 Comments

December 22, 2017 by Amalia Rubin

All I Want for Christmas…

flickr.com/wiccan_woman

It’s that time of year again. Tinsel and lights decorate houses, Starbucks smells of nutmeg and peppermint, and I have spent a lot of time having my all-time least favorite conversation: “Why don’t you celebrate Christmas?”

You would think that “Well, we’re Jewish” should be a good enough answer for people. But apparently, it isn’t. This constantly turns into a long, in depth conversation where I have to defend my right to not celebrate a mainstream Christian holiday.

And sometimes, the conversation takes a turn into the even-more unpleasant.

- 1 Comment

December 21, 2017 by Helene Meyers

7 Jewish Feminist Highlights of 2017

2017 has been a doozy of a year. It’s tempting to fall into despair or to become inured to news that goes from bad to worse. But we need to resist and to persist—and to do that, we need sustenance. The following have functioned as Jewish feminist manna for me this year, and I hope that Lilith readers find these 7 highlights of 2017 nourishing as well. (For those curious, 7 is the number associated with creation and blessing in Jewish tradition!)

1) Thanks to a lawsuit brought by Renee Rabinowitz, a retired lawyer and Holocaust survivor in her 80s, El Al airlines will no longer be able to ask women to change their seats to accommodate ultra-Orthodox men. As someone who wrestled with such a request on my first trip to Israel, I am inspired by Rabinowitz’s pursuit of justice and gender equality.

2) Jewish feminists had a banner year at the movies, with Gal Gadot playing Wonder Woman and Orthodox director Rama Burshtein showing her range with The Wedding Plan, whose comic pathos sharply contrasts with the intensity of her 2012 Fill the Void. But my favorite flick this year was The Women’s Balcony, (directed by Emil Ben Shimon and written by Shlomit Nehama) about the religious intolerance, activism, and alliances that result when a slick but nefarious rabbi inserts himself into a spiritual void. This smart movie with heart and hope tackles the issue of Jewish communities riven by gender fundamentalism.

https://www.menemshafilms.com/womens-balcony

- 6 Comments

December 19, 2017 by Rishe Groner

What “Maoz Tzur” Has To Do With Our #MeToo Moment

Judith with the head of Holofernes, painting by Vincenzo Catena

“Maoz tzur yeshuati…” rings a song chanted the world over following the kindling of the Hanukkah lights, best known in its translation, “Rock of Ages.” Though it wasn’t my family’s custom to sing this seven-paragraph tribute to Jewish resistance overcoming oppression, I was somewhat familiar with not only the famous first verse, but also with the second-to-last. That penultimate verse is a tribute to opposing the Hellenist oppression featured in the Hanukkah story. It includes a phrase that’s been put to countless Hasidic tunes, and always leaves me jumping with joy inside.

“Yevanim nikbetzu alay,” it begins. “The Hellenists gathered against me, in the days of the Hasmoneans.”

Then the language does more than I could ever describe, so let’s go on a journey through the Hebrew:

“Upartzu chomot migdalay“—“and they breached the walls of my towers”/

“V’timu kol hashmanim“—“and defiled all of the oil.”

- No Comments

December 18, 2017 by Rishe Groner

Hanukkah: Fiery Feminist Holiday or Women’s Consolation Prize?

Print, “Judith with the Head of Holofernes,” 19th century, unknown artist.

Since I was raised as a child in an Orthodox community, Hanukkah was the closest thing I had to a feminist holiday.

I grew up in Australia, where I celebrated Hanukkah at summer camp with a menorah lighting that rivalled Shabbat for its beauty and community. We sang “Hanerot Hallalu” with the traditional Hasidic melody and danced around the dining room with our arms around each other. We played variations of dreidel throughout the festival and doughnuts were currency in the camp black market.

One of the ways we learned of the story of Hanukkah was through children’s story tapes. Along with catchy tunes about spinning dreidels and lighting the candles from left to right, it featured the type of song that was rare in my diet of traditionally Orthodox Jewish children’s media—a homage to women, and their contribution to the Hanukkah story.

- 1 Comment

December 18, 2017 by Elissa Cahn

Songsters: Hanukkah Drama Through the Eyes of a Five-Year-Old

www.flickr.com/cogdog/

1.

The Hanukkah candles are lit, and my mother is leaving us. The year is 1986; I am five years old.

- No Comments

December 14, 2017 by Rabbi Rachel Schmelkin

Not Alone: “Righteous Gentiles” Protected Me at Charlottesville

Muslims form a protective circle around Jews praying at a synagogue in Oslo, Norway, 2015.

It was a buggy, Wednesday evening on August 9 in Charlottesville. I stood in the parking lot of Sojourners Church after attending one final, non-violent direct action training prior to August 12. There was a sense of fear and trepidation in the thick humid summer air. Perhaps you felt it too, wherever you were.

I had a plan for August 12. I would stand on the steps of First United Methodist Church, often called FUMC, bear witness to the rally in the park, just across the street, and drown out the sound of hate with music of peace and love. But I was afraid to station myself so close to the park. My Muslim friend, who initially planned to sing on the steps with me, decided that it would be too dangerous for her to be visible wearing her hijab, so she took another important—but less public—role that day. I wondered if I should follow her lead, and get out of sight. What if neo-Nazis or white supremacists attempted to enter the church? What if they stormed the steps where I would be standing in my tallis and kippah?

- No Comments

December 13, 2017 by Nechama Liss-Levinson

#MeToo: The Saga of Bilhah, Zilpah, Hagar, and the List Goes On…

At its best, Judaism offers me an existential anchor in life’s difficult times–for example, in the laws and customs dealing with death and mourning. But at its worst, Judaism’s patriarchal underpinnings and assumptions cause me both grief and anger. The Torah portions in the book of Genesis, which we read at this time of the year, are filled with stories of creation, of the world, of families, of nations and of the Jewish people.

At its best, Judaism offers me an existential anchor in life’s difficult times–for example, in the laws and customs dealing with death and mourning. But at its worst, Judaism’s patriarchal underpinnings and assumptions cause me both grief and anger. The Torah portions in the book of Genesis, which we read at this time of the year, are filled with stories of creation, of the world, of families, of nations and of the Jewish people.

But in full sight are numerous heart-rending #MeToos, sexually questionable and at times sexually abusive relationships between the men and women who are our forebears; for example, between Abraham and Sarah’s handmaiden Hagar, and between Jacob and the handmaidens of Rachel and Leah, namely Bilhah and Zilpah. In both narratives, the wives offer up their slaves to become impregnated by their husbands. The slave becomes a kind of surrogate mother, enacting the hope that the “real” wife will thereby become a mother.

- 2 Comments

December 12, 2017 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

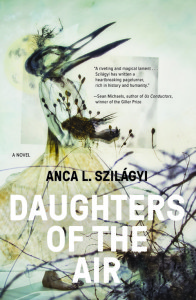

A Conversation With Anca L. Szilagyi

Tatiana “Pluta” Spektor was a mostly happy, if awkward, young girl—until her sociologist father was disappeared during Argentina’s Dirty War. Sent a world away by her grieving mother to attend boarding school outside New York City, Pluta wrestles alone with the unresolved tragedy and at last runs away: to the streets of Brooklyn in 1980, where she figuratively—and literally—spreads her wings. Told with haunting fabulist imagery by debut novelist Anca L. Szilagyi, this searing tale of love, loss, estrangement, and coming of age, Daughters of the Air, is an unflinching exploration of the personal devastation wrought by political repression. Szilagyi, whose story “The Street of Deported Martyrs,” won Lilith’s 2017 Fiction Contest, talked with fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about what drew her to this brutal period, and, on a lighter note, about her ongoing romance with food.

Tatiana “Pluta” Spektor was a mostly happy, if awkward, young girl—until her sociologist father was disappeared during Argentina’s Dirty War. Sent a world away by her grieving mother to attend boarding school outside New York City, Pluta wrestles alone with the unresolved tragedy and at last runs away: to the streets of Brooklyn in 1980, where she figuratively—and literally—spreads her wings. Told with haunting fabulist imagery by debut novelist Anca L. Szilagyi, this searing tale of love, loss, estrangement, and coming of age, Daughters of the Air, is an unflinching exploration of the personal devastation wrought by political repression. Szilagyi, whose story “The Street of Deported Martyrs,” won Lilith’s 2017 Fiction Contest, talked with fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about what drew her to this brutal period, and, on a lighter note, about her ongoing romance with food.

YZM: Tell us about Argentina’s Dirty War, and how you became interested in it.

ALS: Argentina’s Dirty War occurred roughly from 1976-1983 (the exact beginning is fuzzy). In this time, a right-wing military dictatorship “disappeared” up to 30,000 people; that is, anyone suspected of dissent was arrested or kidnapped, imprisoned, tortured, murdered. Suspicion of dissent was quite wide-ranging. One could simply be in the wrong profession (writers, journalists, lawyers, professors, students, activists) or in the wrong person’s address book or in the wrong group of people. Jews were disproportionately targeted.

- 1 Comment

Please wait...

Please wait...