The Lilith Blog

August 29, 2019 by admin

Why We Protested Amazon on Tisha B’Av

By Rabbi Salem Pearce

A few Sundays ago, I found myself browsing in the recent nonfiction section of an Amazon retail bookstore in midtown Manhattan. I picked up Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup, by John Carreyou, the Wall Street Journal reporter who uncovered the massive fraud perpetrated by Theranos and its founder and CEO, Elizabeth Holmes. I’ve already listened to a podcast and watched a documentary on the same topic, but I am am fascinated by corporate chicanery. (Plus, Elizabeth Holmes went to my high school in Houston, Texas.) I was so absorbed in making a note on my phone to buy the book that I almost didn’t notice the group of people, holding signs above their heads, slowly and silently filling up the store. I scrambled to put the book back on the shelf. It was time to turn my attention to another Silicon Valley startup behaving badly.

Photo Credit: Gili Getz

- No Comments

August 27, 2019 by Rebecca Katz

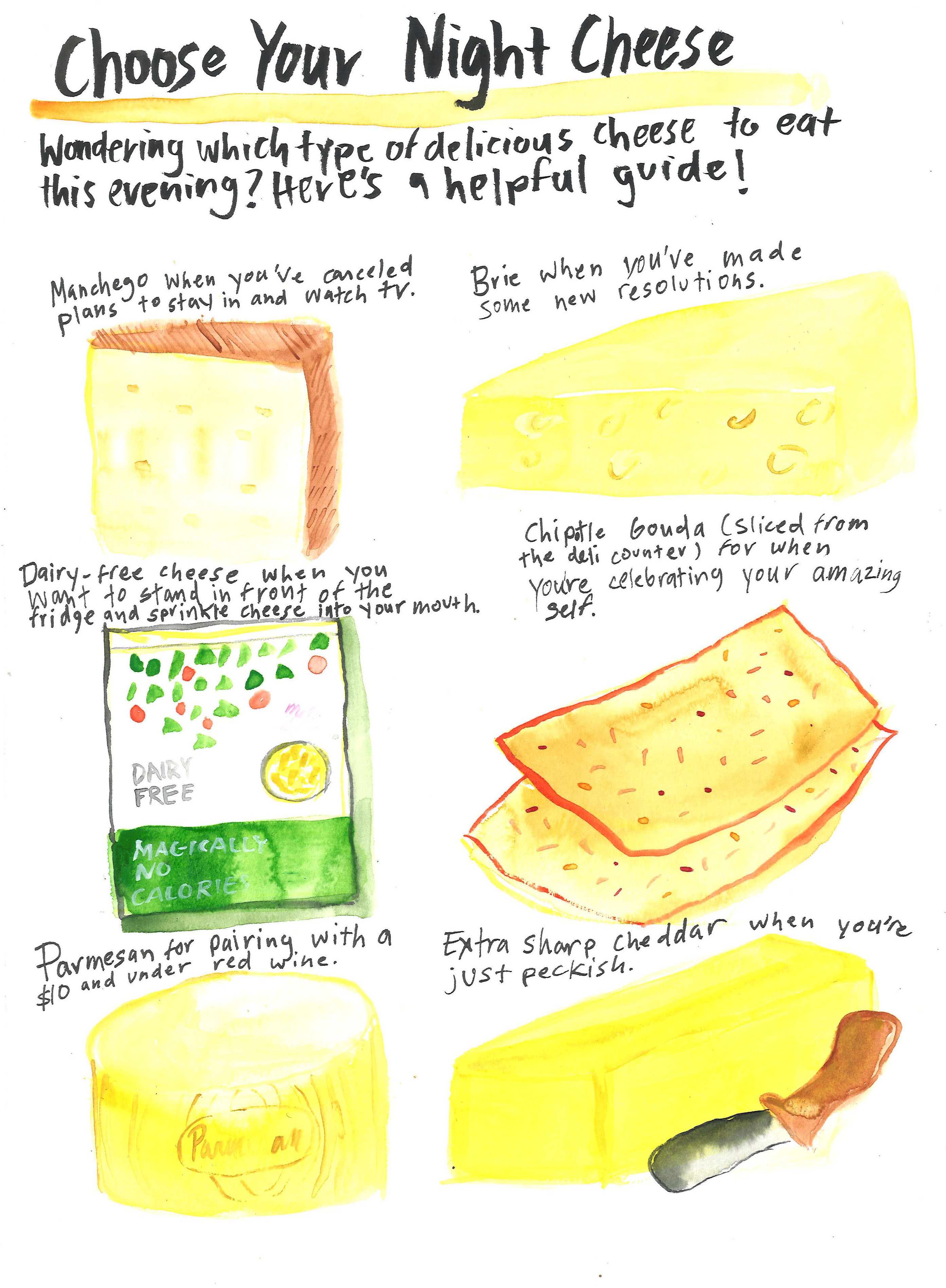

Choose Your Night Cheese

Lactose intolerant or not, we all love cheese. Especially as a late night treat! Use this guide to help you decide which cheese fulfills your snacking needs.

Rebecca Katz is your average white, Jewish, twenty-something who likes to talk and draw about food, privilege, television, and her period. After six years away, Rebecca has returned home to Brooklyn and lives just three blocks away from where she grew up. Take a look at more of her comics at katzcomics.tumblr.com.

- No Comments

August 26, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

A Twist on Doctor-Patient Confidentiality

Radiologist and debut novelist Heather Frimmer tells the story of a mother planning her daughter’s wedding just as she receives a diagnosis of breast cancer in her new novel Bedside Manners. Frimmer talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about how her medical training shapes her life as a writer.

YZM: How did your own training as a doctor influence the writing of this novel?

HF: I work full time as a radiologist specializing in breast imaging. I interpret mammograms, discuss results with patients and perform breast biopsies.

Joyce’s story was inspired by the thousands of breast cancer patients I’ve had the honor of caring for. I used my observations to make Joyce’s journey as authentic and emotionally resonant as possible. Some of the events in Marnie’s story were inspired by or loosely based on situations either I or my friends experienced on the wards during training. I wanted to explore the doctor-patient relationship from both sides. Choosing both a mother and daughter as the protagonists allows the characters to witness and experience both sides of the relationship alongside the reader.

YZM: Why did you make Marnie a surgeon rather than a radiologist?

HF: I would have loved to make Marnie a radiologist, but I knew it wasn’t the right choice. Radiologists stare at computer screens in dark rooms while drinking endless cups of coffee—the opposite of dramatic. Making Marnie a surgeon allowed me to put her in more precarious and emotional situations and raise the stakes for her a lot more.

YZM: The men in the novel respond very differently to the news of Joyce’s cancer than the women; care to comment?

HF: That’s such an interesting observation. This wasn’t a conscious choice, but I think the difference comes from my personal experience. The men in my life tend to underplay their emotional reactions, only getting upset in the most dire of circumstances. The exception to this rule would be my wonderful husband who wears his emotions on his sleeve without shame.

YZM: During the course of the novel, Marnie struggles with her decision to marry a non Jewish man. Were you making a larger statement about intermarriage between Jews and Gentiles?

HF: My goal was not to be prescriptive about intermarriage, but rather to raise questions so readers can think about the issue for themselves. Spouses will inevitably differ in countless ways and learning to negotiate those differences is crucial for a successful marriage. As an obsessive reader, if I can remain happily married for nearly seventeen years to someone who reads less than one book a year, then anything is possible. The keys are open communication, dedication, and acceptance on the part of both partners.

YZM: Do you think you’ll use your medical background in writing your next novel?

HF: I am finishing edits on my next novel which follows a male neurosurgeon with an addiction to pills who makes the decision to operate on his sister-in-law’s brain. The story explores how this decision affects not only the course of both of their lives, but of their entire family as well. I love the way my publicist describes this book—” a complex tale of addiction, love, and survival on the operating table.” While this novel does take place in the world of medicine, it strays much further from my area of expertise. This one required a lot more research to get the details right.

YZM: What’s one question that you wished I’d asked but didn’t?

HF: I like credit to the authors who have inspired me to become a writer. Lisa Genova, the author of Still Alice and Every Note Played, along with several other wonderful novels, has been my major inspiration. I love how the way she uses her expertise as a neuroscientist to explore the details of a specific neurologic disease, its emotional ramifications and the ways the disease impacts everyone in the patient’s sphere. I’d be hard pressed to pick a favorite—her books are all that good.

I also deeply admire Jennifer Weiner’s writing—I faithfully read her novels the day they are released. The way she can make a story hilarious and compulsively readable while addressing serious topics is truly admirable. Her newest novel, Mrs. Everything, just came out in June and is her most ambitious novel yet. She’s truly outdone herself with this one.

- No Comments

August 22, 2019 by admin

In Tennessee, Fighting Back as a Jew Against the Abortion Ban Hearing

By Laurie Rice

On August 13, testifying against the comprehensive abortion ban being considered by the state legislature…

To the Senate Judiciary committee—thank you for having me here today. I am honored to speak before you. My name is Rabbi Laurie Rice. I have been an ordained rabbi for 18 years. A graduate of Northwestern University, I received my Masters of Hebrew Letters and rabbinic ordination from the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion. I serve on the Ethics Committee for Alive Hospice and as an Ambassador for the Amend Program through the YWCA, which works to end domestic violence in Tennessee by helping men and boys become better versions of themselves.

In the summer of 1996, I moved to Israel for my first year of rabbinic school. I lived in Jerusalem, with others studying to become rabbis, for our first of five years’ study towards ordination. That year, I met the man who two years later would become my husband. To be honest, when we went for our pre-marital counseling, we were each asked how many children we wanted to have. My husband said five. I said one. We had some things to talk about!

I said I wanted one child, but really I wasn’t even sure about having any. I was only 28. But then one day, not long after, I was ready. And when that happened, I couldn’t have a child fast enough. I was so excited to be a mom, and I couldn’t wait for my husband to be a father. I knew he would be amazing.

It didn’t take us long to get pregnant, much to my husband’s dismay. We were on our way. We bought the necessary prenatal vitamins, said goodbye to wine and raw fish, and visited the doctor for all the prescribed appointments. And then, at 22 weeks, we learned that our fetus wasn’t growing as it should, and it turned out, after a series of tests, that our fetus was a triploid, meaning it had 3 sets of every chromosome where a healthy fetus has two. I hoped this meant our baby would be bionic, but what it really meant was that our fetus would likely not come to term, and if it was born it would not make it even one year.

We. Were. Crushed. We were given two choices. To go forward and see what happened. Or to have a second trimester abortion. I sobbed. Day in and day out, I sobbed. I sobbed about the baby I would not mother. I sobbed about the dreams that died in that very moment. And I knew right away that I wanted to have the abortion. Because I wanted to have a baby. I wanted to be a mother. And I couldn’t do that until we could start over and try again.

This is not a debate between those who are for abortion and those who are against it. No one I know is FOR abortion. If a woman finds herself in a situation in which abortion is a consideration, she is in distress, and the alternative is most often either mentally or physically impairing. Or both. The debate over abortion is, in fact, a debate over a woman’s right to choose—but in our great nation today, that right has become primarily a matter of faith.

As I am in the business of faith, allow me to say a little more about this. When Alabama Governor Kay Ivey signed into law one of the nation’s most restrictive abortion bans, she invoked her faith. She said, “To the bill’s many supporters, this legislation stands as a powerful testament to Alabamians’ deeply held belief that every life is precious and that every life is a sacred gift from God.”

In January, the speaker of the Virginia House of Delegates, Kirk Cox, cited the Book of Psalms when he came out against a proposed bill that would lift restrictions on abortions. He quoted Psalm 139: “You knit me together in my mother’s womb. You watched me as I was being formed in utter seclusion as I was woven together in the dark of the womb. You saw me before I was born.”

Let me tell you how I, a rabbi, read the scripture. I, too, believe that every life is precious and a gift from God.

However, while my Christian colleagues and friends understand a fetus to represent human life, the Jewish tradition, the foundation of Christianity, does not believe that the fetus has a soul, and it is therefore not a life, as it is written in Genesis: “And God breathed the soul of life into human, and they lived.” Furthermore, Judaism refers to the fetus in Hebrew as a rodef, a pursuer. The rodef or fetus only exists because it feeds off the mother. In fact, if the presence of the fetus puts the mother’s life in danger, abortion is condoned. The wellbeing of the mother takes precedence. Existing life takes precedence over potential life, and a woman’s life and her pain take precedence over a fetus.

But the strongest argument in our Bible for permitting abortion comes from Exodus, Chapter 21, verses 22-23: “If people are fighting and hit a pregnant woman and she gives birth prematurely but there is no serious injury, the offender must be fined whatever the woman’s husband demands and the court allows. But if there is serious injury, you are to take a life for a life.”

The words “gives birth prematurely” could mean the woman miscarries, and the fetus dies. Because there’s no expectation that the person who caused the miscarriage is liable for murder, Jewish scholars argue this proves a fetus is not considered a separate person or soul.

Jewish law is also helpful when discussing abortion. The Talmud, our compendium of Jewish law, explains that for the first 40 days of a woman’s pregnancy, the fetus is considered “mere fluid” and considered part of the mother until birth. The baby is considered a nefesh, Hebrew for “soul” or “spirit” once its head has emerged, and not before.

Furthermore, Jewish tradition and scholars have also acknowledged a pregnant woman’s potential “great need” to terminate a pregnancy. It is clear that in Jewish law an Israelite is not liable to capital punishment for feticide…. An Israelite woman was permitted to undergo a therapeutic abortion, even though her life was not at stake…. This ruling applies even when there is no direct threat to the life of the mother, but merely a need to save her from great pain, which falls within the rubric of a “great need.”

Now you might be saying, “I really hope she stops quoting scripture and makes a point!” Christians and Jews could go back and forth all day long on the interpretation of scripture, because interpretation cannot be objective by the very definition of the word “interpretation.” Throughout history, scripture has been used to legitimize all kinds of evil and depravity, such as the decimation of Jews in Europe, and the right to enslave black people here in this great nation. I can tell Christians that they are interpreting scripture incorrectly, and they can say the same about me. Can any of us truly know what it is that God wants? Who among us is so full of hubris to say that we know? In a nation founded as a wellspring for all faiths, races, and creeds, do we really want to allow for one religious group to prescribe rules and decisions for all, based on one particular interpretation of scripture?

That is not America. America is about religious freedom, is it not? There is no doubt that faith informs each of our views on a variety of subjects, but that’s exactly what they are—personal views, not something for everyone else to comment or legislate on.

If this hearing is about the constitutionality of this particular bill banning all abortion, ask yourself: Are you prepared to admit that you prefer an America that is not based on religious freedom? Are we, the great state of Tennessee, prepared to join the march in making that declaration?

True religious freedom, if you value that, is a shield to protect all religions, and it is never a sword to discriminate. My tradition, the Jewish tradition, teaches that women don’t have abortions they want. I can promise you that I did not want a triploid fetus. (And Senator Bowling, since you brought up the issue of percentages, noting that only 1% of pregnancies derive from a situation of rape, allow me to point out that only 1-2% of pregnancies result in a triploid abnormality. If you are the 1% with a triploid, or the 1% who is raped, then it’s 100% for you. Period.) I did not want to learn at nearly 6 months of pregnancy that I would likely not give birth to a live baby, and that if I did it would most certainly die within the first year. Women do not have abortions they want. They have abortions they need.

To ban abortion is to blatantly diminish the rights of women to advocate for what they need. How many of you men would honestly feel comfortable with your same rights diminished?

Laurie Rice is the co-senior Rabbi of Congregation Micah in Brentwood, Tennessee. She serves alongside her husband, Rabbi Philip “Flip” Rice. When not leading and pastoring to her community or taking on a variety of social justice issues, she runs miles on the roads and trails of Nashville and hangs out with her kids.

- No Comments

August 20, 2019 by admin

What the Editors Never Knew About a Lilith Cover!

In 2010, when my then teenage daughter Emma was a camper at URJ Olin-Sang-Ruby Union Institute (OSRUI), I went into a local bookstore to find an appropriate book to add to a care package we were sending her. I told the salesperson that I wanted something for a strong, self confident, feminist Jewish young woman. I was expecting a new book but she took me over to the magazine rack instead, explaining that she had the perfect magazine for her. She pulled out Lilith and said why its mission and purpose fit exactly with my objectives, giving it to me to look at.

The cover story of that issue featured a lesbian rabbi from Philadelphia who had raised this amazingly diverse family of 5 kids as a single mom. Three of her kids were her own biological children from 2 different donors, and the other two were adopted from Guatemala. It was an inspiring story of love, commitment, Jewish life, family solidarity and diversity, and the importance of cultivating strong individuals.

As I looked at the front cover I recognized the people and the story of Rabbi Julie Greenberg immediately: Julie is my sister-in-law (my wife’s sister), and the children are my nieces and nephews—Emma’s aunt and cousins.

The salesperson asked, “Do you think this would interest Emma?”

I smiled and said, “Yeah, I think she might be interested!”

Andrew Rehfeld is the President of Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion. This recollection is from his welcoming remarks at a launch party for Lilith’s summer 2019 issue held at HUC’s Dr. Bernard Heller Museum in Manhattan on August 14, 2019.

- No Comments

August 20, 2019 by admin

Talking Back to The Red Tent in the #MeToo Era

I assign Anita Diamant’s novel The Red Tent in my Women in the Hebrew Bible course because it helps students learn about the concept of midrash and highlights just how little the biblical text itself centers women’s experiences and relationships. Plus, it’s a fun read! But times have changed in the 22 years since Diamant reimagined the tale of Dinah’s rape (or perhaps, since Biblical Hebrew lacks a word for rape, her “sexual humbling”) in Genesis 34 as a love story. Our societal understanding of rape, rape culture, and consent has evolved, particularly in the wake of the #MeToo movement calling powerful men to account for sexual harassment and sexual assault. Thus, when I ask students to respond in writing to The Red Tent, one question is, “Is Diamant’s midrash a feminist one? Can the redefinition of (possible) sexual assault as consensual sex be a feminist enterprise?”(Consider the following from Diamant’s website: ‘I could never reconcile the story of Genesis 34 with a rape, because the prince does not behave like a rapist. After the prince is said to have ‘forced’ her (a determination made by her brothers, not by Dinah), he falls in love with her, asks his father to get Jacob’s permission to marry her, and then agrees to the extraordinary demand that he and all the men of his community submit to circumcision.’) Students may respond to their chosen questions in essay format or in another medium, such as poetry or visual art.

When I taught the course in Fall 2018, two students coincidentally chose to write poems addressed to Diamant from Dinah. I was struck by how different their viewpoints were. One student, Muktha Nair, referenced class discussions about whether we can consider what happened to Dinah “rape.” That debate will never be resolved, Nair suggested. In a note accompanying her poem, she wrote, “Would a little girl want her name to be limited to the debates under literary scrutiny among biblical scholars and the clergy? Wouldn’t she much prefer to flourish and become immortal through folktales and mystical stories of being the knowing woman, the skilled midwife, a lover?… And that’s where I concluded that Diamant wasn’t doing a disservice to Dinah! By giving her a form, thoughts, a voice, a life, Diamant is ensuring that Dinah’s name lives through the eras to come. All we can give to Dinah is a lasting place in the thoughts of humanity—not as an object of debate, but as a Woman.” In her poem, Nair, writing as Dinah, thanks Diamant for giving her new life.

The other student, Sara Milic, wrote a poem comparing Diamant’s treatment of Dinah to a second rape. In the note accompanying her poem, Milic wrote, “This poem gives Dinah the opportunity to finally speak and to tell the truth herself. This also gives Dinah the opportunity to address how she might possibly feel about Diamant changing her story of rape into one of love. I felt a poem would be able to match the drama of the actual situation both in Dinah’s rape and in Diamant’s silencing of Dinah’s rape. I’m paralleling Dinah’s rape to Diamant silencing her by making similarities in both attacks (foreign prince, covering mouth, silencing, etc).” Milic’s poem has Diamant taking from Dinah what isn’t hers: Dinah’s story.

When I read these two poems, one right after the other, I immediately thought of seeking to publish them in Lilith. These two college students struggling with questions of sexual assault and female agency in a 2,500-year-old text and a 1990s bestseller have produced powerful poetry.

Caryn Tamber-Rosenau is instructional assistant professor of Jewish Studies and Religious Studies at the University of Houston. She is the author of Women in Drag: Gender and Performance in the Hebrew Bible and Early Jewish Literature (Gorgias Press, 2018). She is a former Lilith intern.

_____________________________________________________________________________

By Muktha Nair

To my daughter

Through whose words,

my soul lives on.

Some say I was raped,

But the world is yet to know the truth,

One that cannot be avenged, in my name.

But you, my Anita,

You have given me voice.

No longer just a forgotten name

Among words,

Written by men who know not.

You, as a fellow woman,

Have fulfilled the secret womanly vow,

By ensuring utterance of my name

giving a life to my name,

Thoughts to my name,

A voice to my name.

Giving me a place in the hearts of all;

Realizing the debacles of debates

Only wither away at the little felicity

Left for me.

Now my name

will be remembered,

In love,

In pain,

At birth

At death.

Not as a cursed whore;

But as a knowing Woman.

A Note to Anita by Sara Milic

I am being stripped of my story

You’re covering my mouth

I can’t breathe, I’m panicking

You were supposed to be the knight on the white horse,

The foreign prince coming to save me

You tricked me with your stories of sweet bread

And nights of cuddling in the tent

I trusted you, my sister, to let my soul go free

To unleash me from this burden I’ve been carrying

To tell my truth, to expose my aggressor

Anita, I’m crying – can’t you hear me?

Tell them he raped me, Anita

Are you listening?

You changed my story

I know it’s hard to read

My sister, I wish I could forget it

You’ve taken from me, just as he did,

My voice and my sense of self

Will there ever be justice for me,

Or for the sisters before me?

Will the sisters after me be believed?

Anita, will you be the savior of the silenced?

Or will you lay your hand over their mouth,

And take from them what isn’t yours to keep?

Don’t tell them he loved me,

Don’t lie and say I loved him

Please, don’t tell them I was happy

When will my rape end?

- No Comments

August 19, 2019 by admin

Sexism is Routine for Female Clergy

A female cantor walks into a funeral chapel. The funeral director says, “Nice to meet you, Cantor. Turn around and let me see the rear view.”

Rabbis and cantors who are also women hear some version of this from time to time, but less frequently today than 40 years ago.

Although we’re aware that it’s impossible, many of us try to dress in a way that’s designed to prevent sexist comments. By keeping our necklines high and our hemlines low, by avoiding anything clingy, we work at a calculus that has variables clearly beyond our control. Our sought-after formula usually depends on some perfect calibration of the “female” aspect of the term female clergy and the “clergy” part. If nothing else can, the theory goes, looking HOLY should shut it all down.

A holy “look” has been in fashion at least since biblical times. Back then, priests wore all kinds of special accessories, from jeweled necklaces to embroidered epaulets. Their clothing was adorned with bells to announce their presence. Priests were supposed to stand out in a crowd. They enjoyed high status. After all, they were carrying out sacred rituals—theatrical ones, at that. Think incense, flambéed meat, and the mandated sprinkling of animal blood. Sacrifices had to be made in a specific order and accompanied by incantations. The priests played their heavily costumed role so that Israelites could appease their God with majesty.

As the centuries rolled by, synagogue and church ceremony began to rely more on words than burnt offerings. But the glitz remained a fixture. Glitz filled pews.

In the Middles Ages, Western literature started describing the bodies UNDER the clerical stylings. Not uncritically. In Chaucer’s Clerk’s Tale, a student priest is thin. Robin Hood’s Friar Tuck is large. Friar Tuck is judged to be too worldly, too self-indulgent. What religious standards could someone like that uphold? Chaucer’s student priest might have more spiritual discipline. But how compassionate can a self-denier be?

These assumptions never had anything to do with actual ministry. Instead, they satisfied the human need to criticize those who purportedly rank higher on the holiness scale.

When women began to shatter stained-glass ceilings, some congregational eyebrows hurtled skyward. The very presence of female officiants was startling to some and objectionable to others. Now, in 2019, although women clergy are old hat, some men can’t adjust to the existence of clergywomen. Period.

We women clergy remember the black-robe-related comments—generally imaginative speculation about what we might be wearing underneath those robes. Well, black robes are going the way of the dinosaur. Today, clergyfolk dress like the regular people we are.

But whether clergy dress like everyone else or not, a distinct problem for women persists. It’s the same problem that has always dogged women and girls: the objectification of our bodies—and the attendant rumination about them.

Here’s what’s worse: We women have learned to become watchful and wary because we’ve internalized the objectification. How do I LOOK from the bima? we wonder. What image am I conveying to congregants? we ask ourselves. Do I look approachable? If I’m going for “humble dignity,” do I wear a jacket?

And this watchfulness isn’t limited to how we style ourselves. Many of us are hypervigilant about diet or exercise, too. And so we interrogate ourselves further: If I post a Facebook pic of myself looking sweaty and triumphant after a run, am I modeling healthy behavior? What about the late summer profile pic where my cellulite can be seen with the naked eye? If I’m going for “cheerful cred,” do I share the image of my hand around my industrial-scale chocolate ice cream cone?

The prevalence of stupid remarks contributes to our self-objectification. But it’s up to us to resist.

Last week I participated in a shiva service for the dad of a dear friend. My friend’s house was packed. As I was greeting people afterward, the effort of talking loudly enough to be heard over the crowd made me start to cough. One 50-something man said to me, “Do you need the Heimlich maneuver? Performing it on you would be fun for me!”

In the past, I’ve ignored such comments or even ruefully smiled at them. Last week, as I stared back at the man with incredulity and disdain, I let his words dangle alone in the air, exposed.

Obviously, we can’t completely escape degrading remarks yet, but I for one am over giving them a pass.

Maybe we women clergy—and our brothers, sisters, and gender-nonconforming siblings who are also the objects of profane jokes—should start a retro trend and bring some ancient priestly accessories into the twenty-first century. The ringing of these bells would warn, “STFU.”

Barbara Ostfeld, at age 22, became the first woman ordained as a cantor in 3,000 years of Jewish history. Her essays have appeared on the Lilith Blog, in the book New Jewish Feminism, and in 10 Minutes of Torah, a daily email that brings the Reform Jewish world to subscribers worldwide. Ostfeld’s memoir, CATBIRD: The Ballad of Barbi Prim, was published in 2019 by Erva Press. She will be honored with the Debbie Friedman award at the 2019 URJ Biennial this December.

- 2 Comments

August 15, 2019 by admin

“Ask For Jane” Tells the Abortion Story You Never Heard, But Should Have

For those of us born at the tail end of the 20th century, a world without legal abortion is tough to imagine. Bluntly showing a society in which unwanted pregnancies can quickly become death sentences and where even talking about abortion can lead to jail time, newly released biopic “Ask for Jane” makes sure we know exactly what this world looked like.

The film, directed by Rachel Carey and released one short year after Lilly Rivlin’s documentary “Heather Booth: Changing the World,” tells the story of the Jane Collective, an underground, illegal abortion service run out of Chicago between 1968-1973. Created by a college student who connected pregnant women with abortion doctors through her dorm room phone, the “Janes” developed into a volunteer network dedicated to providing safe abortions to women at the lowest possible cost. In 1971, after discovering that one of their “doctors” faked having a medical license, a number of the Janes even became “abortionists” themselves, doing the procedure for whatever price each woman could afford to pay. The makeshift clinic was eventually raided in 1972 and led to the arrest of seven volunteers who would become infamous as the “Abortion 7.” Despite facing up to 110 years in prison, the Janes continued helping pregnant women while out on bail. All charges against them were dropped shortly after abortion was made legal nationwide. In the final years before Roe v. Wade was decided, the Janes provided 11,000 women with safe abortions.

Far from devolving into partisanship, “Ask for Jane” stresses that the right to abortion is imperative for every woman regardless of whether she is Democrat or Republican, Catholic or atheist. All women can find themselves pregnant when they don’t want to be. All women are on the losing side of the war. The film shows teenagers, rich Park Avenue wives, low-income workers, survivors of rape, college students, women of color, mothers—every imaginable type of woman in the clinic waiting room. Speaking at a talkback following a screening of the film in Manhattan, creator and star of “Ask for Jane” Cait Cortelyou pointed to this diversity as the most important aspect of the movie. “I was interested in humanizing those stories,” she said, “because I feel like a lot of the conversation has gotten away from the individuals who are affected by the policies that are made.”

Yet, beyond reinforcing the necessity of safe, legal abortion for all women and introducing audiences to a badass activist group that is ignored in high school history class for the sake of covering more white guys, “Ask for Jane” distinguishes itself by representing a brutal and holistic picture of women’s reproductive welfare that extends far past abortion itself.

The lack of knowledge surrounding sex, for instance, is consistently cited as a major cause of unplanned pregnancy throughout the film. One of the characters—all of whom are fictionalized—works at a Catholic high school where she smuggles sex ed pamphlets to students, raging that abstinence-only education leaves kids clueless and at risk. Today that simple fact remains true, with those schools and states teaching girls to keep their legs closed having higher teen pregnancy rates than their condom-wielding, pill-popping counterparts.

The overwhelmingly patriarchal nature of society at the time (today too, let’s be real) further stands as a clear impediment not only to women’s autonomy but also to their general health. A newly engaged character asks an elderly, male gynecologist for a birth control prescription. He refuses to give her one on the grounds of her unmarried status. Luckily, he assures her, if she returns with a husband who will give his permission, she can get the pill. Similarly, a pregnant mother of two learns that a tumor in her abdomen can be removed, but she runs the risk of losing her baby in the process. Though she immediately agrees to the surgery that will save her life, it’s not up to her. As the legal owner of her body, her husband gets to decide whether she lives or dies.

Today, in the midst of the most virulent wave of anti-abortion legislation since Roe v. Wade, “Ask for Jane” serves as a reminder that such a vicious restriction as the outlawing of abortion does not emerge in a vacuum and cannot be fought in isolation. Rather it is a by-product of a society run by and for men that considers the purpose of women to be childbearing. Period. Women are denied education regarding their own anatomy and safe sex. They are refused birth control. Men decide what women may or may not do with their bodies. It’s not just that abortion is illegal, it’s that all of society is built for women to have kids—whether they want to or not. And if there is a push to take us back to the days of criminalized abortion, there is a push to restore the larger social order that came with it, something that must be fought with the same fervor as anti-abortion legislation itself.

“Ask for Jane” is not a movie for viewers to leave behind in the theater with sticky floors and popcorn containers. Rather, it is the motivation for burnt-out activists to keep fighting in the face of crushing opposition. It is the hope that all women will unite on this issue and fight for the protection of legal. It is the source of anxiety propelling the idle to action, turning “heartbeat” bills and abortion-provider deserts from headlines on our phones to a bleak reality accessible even to those who never lived in a United States that criminalized abortion. And, most importantly, it is the game plan, reminding us to direct our energies not only to abortion, but to the availability of birth control, comprehensive sex ed, and the abolition of patriarchal culture. To keep the fight for women’s reproductive health on track, movies like “Ask for Jane” are crucial. In the words of Gloria Steinem herself: “It is a movie that should be seen by every American.”

- No Comments

August 13, 2019 by Kathryn Ruth Bloom

Are There Lessons in Quiet Judaism?

Back in junior high school, the girls had to participate in an extracurricular sports team, and my friend Sheila and I played junior-varsity outfield. Sheila was slightly less awful an athlete than I was, and we shared a mutual strategy: since most of our classmates couldn’t hit the ball too far, playing outfield meant that all you had to do was stand around and pretend you were interested in the game. The Phys Ed teachers only paid attention to the athletic girls, which meant Sheila and I could stand near each other and talk about important things, like boys and that cute new social-studies teacher.

There was a small Jewish community in our suburb. In the first community my family had lived in, on the other hand, we were the only Jewish family on the block. And it was a very long block. My parents were quiet about our faith, and told me when I was still a little girl that some people didn’t like Jews and that sometimes I might hear mean comments directed to me. Both my mother and father suffered terrible anti-Semitism in their youth—my father in particular was the object of hideous physical violence that left his face scarred forever—not in Nazi Germany, but right here in America. So they did not deny being Jewish, but were quiet about it, although the mezuzah proudly hanging on our front door might have given things away to our neighbors.

Sheila was Jewish too, and we talked about it sometimes, especially about The Diary of Anne Frank, which staggered us both. We knew about the Holocaust, which took place just before we were born, and we knew that, although Judaism had to go underground at certain times—much in the way the Franks and the Van Daans and Dr. Dussel were hidden in the attic—it was a religion and a people of survival. So we smiled with pleasure when we found out that the young actress who played the Norwegian-American Dagmar Hansen in the television series “Mama” was really Robin Morgenstern, not Robin Morgan. And on the ball field one day, waiting for fly balls that never came our way, Sheila asked if I was still a Girl Scout.

“Yes, I am.”

“Do you read The American Girl?” The Girl Scouts’ monthly magazine featured articles about young women who earned merit badges by picking up neighborhood trash and knitting socks for the poor. It also featured short stories about slender, blonde-haired, blue-eyed girls named Krissy and Gwen and Mary. My friends and I hated our dark, curly hair and dumpy body types and longed to look like them.

“Yes, I do.”

“Did you see it? The name?” We smiled at each other. One of the stories featured a heroine named Shayna, which we knew meant pretty girl. Shayna Punim, the name our grandmothers called us. And this Shayna was more than just a pretty girl; she was a clever girl who sneaked into a story about bland, conforming Middle America.

A few years later, being Jewish became fashionable. Girls flaunted Stars of David to let the Jewish boys know we were available. We bragged that all the best doctors and lawyers were Members of the Tribe, and although the lives of people in books by Philip Roth, Bernard Malamud and Saul Bellow bore only superficial resemblance to our own, they came to define Jewish society in America. We celebrated our leadership in arts and culture, science and medicine, moral righteousness and the quest for social justice. It was an extended moment and lasted many years, but I suspect I’m not alone in thinking that things are changing now. The newspaper columnists and talking heads on television, the young physicians who treated me during a recent hospitalization, the authors of newly-published fiction about coming of age in America are less often Jewish than they are African American, Latinx, or Asian.

That’s as it should be in a country that is increasingly diverse and conscious of different experiences and opinions. Nevertheless, friends who are leaders in the Jewish community worry about the global rise of anti-Semitism, a turning away from Israel, and a general erosion of the centrality of the American Jewish community in the lives of many American Jews. I’m aware of this too, of course, but what gives me confidence in our people’s endurance is that, as my friend Sheila and I recognized as young girls, Jews don’t always have to make a bold fuss about who we are. Like Shayna, we come through.

After retiring from a career in public relations, Kathryn Bloom went back to school and received a PhD in literature from Northeastern University in 2018. She now teaches at several Boston-area institutions and writes critical articles and essays for a variety of publications.

- No Comments

August 12, 2019 by admin

Rewards of a Vintage Clothes Junkie

I’m a hard-core shmatte addict, and nothing makes me happier than pawing through someone else’s discarded clothes, looking for treasures. My hunt takes me from the high end (Housing Works, and the string of charity shops that used to line Third Avenue in Manhattan) to the low (flea markets and the humble-but-reliable Salvation Army) and everything in between. So I was especially eager to check out the once-a-year blowout sale at Marlene Wetherell, one of my favorite vintage dealers in Manhattan. I found myself attracted to a black leather-trimmed wool pants-and-tunic combo that didn’t exactly wow me on the hanger but was so soft and comfy that I decided to give it the proverbial whirl. That’s when the wow became apparent. The seeming effortlessness of it was deceptive—it was as comfy as it had looked, but also pulled together, polished and very chic. The pants fit like a dream and two pieces could be worn together or separately, belted or not. The top allowed for layering, expanding its seasonal range. Clearly the thing had to be mine, so home with me it went.

After it had been introduced to some of the other pieces I imagined pairing it with and had settled happily in my closet, I was curious about the designer, Roberta di Camerino, whose name wasn’t one I knew. I did a bit of Google sleuthing and that was how I found the fascinating story of a can-do Jewish woman who used adversity to spur an illustrious career in fashion. Here’s her story, some of it in her own words.

Born Giuliana Coen in 1920, she was part of a wealthy Venetian family. Her grandfather owned a pigment factory, where young Giuliana became intrigued by the process of color matching, perhaps setting her life on its course (the factory would later become the atelier for her fashion house). At 18, she married Guido Camerino, and in 1943 the couple was forced to flee to Lugano to escape the looming Nazi menace. It was there that Camerino had her aha! moment:

“I was a refugee in Switzerland and I was forced to sell my bag, a leather bucket bag that I bought in Venice. That day I went home with all my belongings in a scarf. The next day I was searching for an economic bag, but I couldn’t find anything fashionable at a reasonable price. So I thought: what if I reproduce with my own hands that bag?

“I bought leather, a ball of string, a curved needle. Briefly I sewed my old bucket bag. I didn’t know I was triggering a mechanism that could change my life forever. The next week a policeman on a train arrested me for smuggling. I discovered that the lady who bought my old bag…was the one who denounced me. I bumped into her after the sale and she saw my new bag, identical to hers: so she went immediately to the nearest police station, accusing me to smuggle leather Italian goods into Switzerland’s market. The misunderstanding was soon cleared up, but that event changed my life. The press was interested too and I received a lot of job offers. So I began to sew bags.”

Talk about turning lemons into lemonade. When the war ended in 1945, Camerino and her husband returned to Venice and settled in their house at Campo Santa Maria Formosa. She then hired a few leather artisans to get started. But the conventional model of a handbag bored her; instead she was eager to create something fresh and original.

“Bags until then were strange objects. Too severe and without colors. There was only one rule to follow: the color of the bag must match with the color of the shoes. So I thought: what if I designed colorful and glamorous bags, that didn’t follow the rules anymore? At Vogini (a high end store in Venice), we put on display a soft leather bag, that could be closed with a double fold: at the time we didn’t know we were doing avant-garde accessories. We had to invent something: a bag should always be a container, maybe more elegant, but surely more outstanding. It was hard to reinvent an object, so closed in its traditions, into something new, then finally the idea came: I had to add something to the leather. I thought I had to create something important.”

She decided to name the fledgling company—as well as herself and later her daughter—Roberta after a film starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. The song Smoke Gets in Your Eyes was the last song that Giulliana Camerino danced to before she had to leave her home for Switzerland and she said she adopted the name as a memory of earlier happier times. She added her husband’s surname, Camerino, to complete it.

By 1947 Camerino’s company had expanded to 10 artisans. It was also the year she became friends with Coco Chanel. “When we met in Paris for the first time, I gave her two bags. She was so enthusiastic that the same night, at dinner, she wore one of them. That night she told me something I would never forget. My husband had just called me from Venice, telling me that the market was full of my bags’ fakes. I called Chanel crying, telling her that I was puzzled and I preferred to stay in my hotel’s room for the night. She laughed out loud and she told me: ‘It’s amazing, there you go! You’ll cry the day they won’t copy you anymore!’”

By 1950, the growing company needed to find a bigger location. Camerino opened her factory near a school-laboratory in Venice, called Zitelle, and part of its goal was to help dropout girls find employment. Her line was beginning to command attention. When Stanley Marcus, the founder of the “Fashion Award,” came to Venice, he visited her factory as well as another artisanal laboratory at Bevilacqua, where antique looms were used to produce high quality velvet for ecclesiastical dress. It was a fortuitous coincidence because Camerino had intended to use that just that kind of precious velvet to create a new type of bag.

“Velvet fascinated me, because of its vibrant colors. Night blue, deep red, bottle green. They matched perfectly. I spent hours and hours searching for the best way to make this brand new fabric work. I sketched a bag, and then another and another one….the essential design of a doctor bag inspired me so much, more than other bags’ shapes. I remembered some boxes set and jewelry boxes..I thought about small buckles and belts…It was a long process…at the end the idea: we had to make a figured velvet for my bags. We could weave buckles and all the other decorations: I mean they would be part of the bag, but they would be an illusion, a trompe-l’oeil.”

Out of this process her most famous bag, the Bagonghi, was born. It was made of colorful velvet, and had an odd shape inspired by Bagonghi, which was the name of the dwarf clown Camerino had seen at the circus as a child. In 1956, Camerino won a Neiman Marcus Fashion Award in recognition of the success and influence of her handbags. Her cut-velvet bags featured brass hardware made by Venetian craftsmen, and were carried by celebrities such as Grace Kelly, Farrah Fawcett and Elizabeth Taylor.

She continued on in this innovative vein, using densely patterned and colored fabrics that in the past been used only for clothing. As early as 1946, she had created a bag patterned with a trellis of R’s, foreshadowing the famous G’s used by Gucci. In 1957, she was using woven leather well before Bottega Veneta made the technique its trademark. And in 1964, she made a handbag with an articulated frame that was later reproduced by Prada.

By the mid 1960’s, she branched out into clothing, and the black ensemble I’d bought was probably from a few years later, sometime in the 1970’s. Some of her fabrics were woven on antique looms, which helped support local industry in post-war Italy. The first Roberta di Camerino fashion show, held in Venice in 1949, was remembered as a quite an elaborate spectacle.

Camerino was keenly aware of how the needs of the modern women had evolved. She wanted to use fabrics that didn’t wrinkle, and designs that were extremely wearable and easy, but also exceptional. “Time has changed. Housemaids, who helped women to get dressed, didn’t exist anymore. And then it was very difficult to match the right T-shirts with that kind of suit or with those jackets. Not to mention traveling. How many times did you happen to forget that specific accessory? So my ideal dress had to solve all your problems: I imagined it as a T-shirt, in which you could slip easily and get ready in one go. For many years I sketched tromp-l’oeil on velvet and one day I decided to apply this unique method also on my dresses. On them I sketched everything a woman should need to feel herself well dressed: buttons, a belt, lapels and the blouse beneath them and even the last buttonhole of the sleeve was undone, just like the most elegant men did. And then a huge variety of prints, which made the history of the tromp-l’oeil.”

In 1980 Camerino closed her fashion house and turned to the lucrative licensing deals for ties, scarves, aprons, and wallpaper. Exhibits of her work—at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Fashion Institute of Technology—soon followed.

In 1996 the Roberta di Camerino label was revived, and began to re-issue the handbags, which were sold through New York and other department stores, including Neiman Marcus, which had been the first American story to carry her line. The Sixty Group acquired the label in 2008, and at that point, many of the licensing deals were terminated.

On May 10, 2010, di Camerino became ill, and she died in Venice that night; she was 89. The Mayor of Venice, Giorgio Orsoni, remembered her as a friend, entrepreneur and an active promoter of Venice and Italian-made goods, especially during the Italy’s struggling post-war years.

I’m not sure why I find it so important to know all this. But I do. Helena Rubinstein, another powerful Jewish entrepreneur, said that for a woman, the act of applying cosmetics was akin to the construction of an identity with which she could face the world. I believe the same can be said of our clothes. And if that’s the case, then understanding the vision that gave rise to a particular garment and the context in which it was made becomes an integral part of that identity. I haven’t worn my Roberta di Camerino pants ensemble yet. But when I do, I hope it will project a bit of the fortitude and grace that helped her create it.

- 1 Comment

Please wait...

Please wait...