The Lilith Blog

September 20, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

“Vera Paints a Scarf”- Honoring the Life and Designs of Vera Neumann

For Proust, a tea-soaked madeleine was the portal to memory, but for me it was the show “Vera Paints a Scarf” at Manhattan’s Museum of Art and Design. The show celebrates not only the scarves but also the tableware, clothing, posters, stationery, and paintings created by the eponymous designer. Back then, I didn’t even think to associate the name, scrawled in loose, jaunty script, with an actual person. It seemed like the name of a product, only slightly more resonant than Kleenex or Mattel, though I did like the little ladybug (more on that later) that was part of the logo.

Instead, I was captivated by the bright colors, the breezy, slightly insouciant style, the sheer joy of the designs, which were easy mix of natural elements like trees, flowers—lots of flowers—birds, insects (that ladybug again) fruits, and vegetables, along with more abstract patterns, some sinuous and lyrical like her paisleys, others more geometric or linear. Of the ladybug she said that it “means good luck in every language.” Both her palette and her aesthetic felt fresh and distinctly modern, the shifts and tunics designed for girls like me, or maybe the girl I aspired to be—think 1960s model Twiggy in one of those little dresses and a pair of go-go boots and you get the idea.

I don’t know how or when I lost track of Vera, though I do recall occasionally encountering the scarves in my perpetual second-hand-shmatte hunt, when such a discovery would be accompanied by a whiff of nostalgia and even melancholy. So walking into the show at MAD was a thrill that brought it all rushing back—color, the whimsy, the echo of the girl I was when I first discovered her.

MAD Museum

- No Comments

September 19, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

When a Toy Dog Became a Wolf and the Moon Broke Curfew…

In this new memoir, Hendrika de Vries’ writes of the dark days in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam as a child, years as a swimming champion, young wife and mother in Australia, and a move to America in the sixties. She talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis about how the brutality of her childhood fostered a strength and resilience she has been able to draw upon ever since.

YZM: How did your mother’s decision to join the Resistance and harbor Nel, a young Jewish woman, affect you as a girl?

YZM: How did your mother’s decision to join the Resistance and harbor Nel, a young Jewish woman, affect you as a girl?

HDV: At the time that my father was deported to Germany, I was an only child surrounded by friends and cousins who all had siblings, and I longed for my own brother or sister. I do not have a clear memory of how I felt when my mother decided to join the Resistance. In a way it seemed a natural progression, because we regularly spent time at the home of the family where members of the Resistance movement met. And when my mother told me we were going to hide a Jewish girl, I liked the thought that I would have an adopted older sibling. I was told that her name was Nel, but in order protect her secrecy I was not given her last name.

After she moved in with us, Nel and I formed a sisterly closeness and often slept in the same bed. In the manner of an older sister, she gave me a sweet diminutive nickname “Hennepiet,” and wrote about our “happy” time together in a poignant verse for the friendship album that girls my age carried around in those days. A copy of her verse with the nickname “Hennepiet” appears in my memoir.

Having been a daddy’s girl for the first five years of my life, I now learned about the comfort and unique pleasure of being in an all-female household. In my memory, my mom and my secret “stepsister” were always brewing pots of coffee and talking. If I close my eyes even today, I can still smell the rich aroma of coffee that permeated our home, and being in the company of their female bantering and laughter made me feel safe. I remember my mom bringing out a coffee-table-sized Old Testament copy of the Bible that had been in her family all her life. It showed full-page sepia illustrations of the Hebrews escaping slavery in Egypt. There was one of the parting of the Red Sea, of course, but the image I liked best was of Miriam, Moses’ sister, and other women dancing as they celebrated their freedom with tambourines. My mom, Nel and I would dance around our dining-room table clanging spoons and shouting “freedom” until my mom shushed us. I loved having an older sister. But I could not talk about her. She had to be our big secret. I could never figure out at six years old why the Nazis wanted to kill her, or might kill my mother and me because we were hiding her. I believe this confusion set me on my lifelong path to try to understand human behavior and my own eventual spiritual quest for the divine.

- No Comments

September 18, 2019 by Eleanor J. Bader

This Woman-Owned Business Has Everything You Need to Dress for Activism

If you like to wear progressive politics on your sleeve—or maybe on your coffee/tea/matcha mug or cell phone case—check out HeedtheHum.com, a queer, Jewish, woman-of-color-owned company created and run by Brooklyn activist Rachel Levin.

Heed the Hum’s nearly 2000 products sport a variety of messages, from the word RESIST to Eve & Esther & Miriam & Deborah & Ruth, a celebration of Biblical sheroes. Other products promote world peace or provide a way to declare one’s identity: Black and Brazen; Nasty Woman; Feminist Zionist, among them.

Levin, a professional graphic and web page designer, sat down with reporter Eleanor J. Bader in early September to talk about the challenges of being a feminist entrepreneur.

Eleanor J. Bader: Let’s start with the name of your company, Heed the Hum. What does it mean?

Rachel Levin: I’ve always been an activist and prideful about being queer, Jewish, and of color. But growing up I had deep moments of unhappiness and feelings of loss. I had been adopted at two months old by a straight, white, Jewish couple in Chicago. I was born in Chile, and for a long time kept my shame over being adopted private; it was always on a back burner of my mind though.

I was raised in a very safe, but sheltered, bubble, surrounded primarily by Ashkenazi Jews. They treated me beautifully, but in my gut, I felt like an “other.” I knew I was Chilean, at least by blood, and even though I had food, shelter, and an incredibly loving family — the best parents and a wonderfully supportive and inclusive older brother who was also adopted—there was always this hum that something was a bit off. For many years, I ignored it.

As I got older, I wanted to live fully, out in the open as a queer person, as a feminist, and as a Jewish person of color. To do this, I literally started to heed the hum, to listen to the signs around me. I began to pay attention to what I was feeling both personally and politically. A bit later, when I was in college, I realized that I wanted to help other people become visible and become empowered by what made them an “other.” I also wanted to do something that would start conversations about political issues.

I started Heed the Hum in May of 2017. In the past two years I’ve sold several thousand t-shirts for adults and children, as well as mugs, hats, pillows, posters, pieces of jewelry, flags, totes, and phone cases. The proceeds of The GIVE Collection benefit organizations I support, like the Red Cross and Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America. It’s work that I think makes a difference.

- No Comments

September 16, 2019 by Kathryn Ruth Bloom

Matzos for the New Year

It’s that time of year when I start to receive calendars from different Jewish organizations, each beautifully designed and intended to remind me of their outstanding work and wish me health and happiness in the new year. I appreciate the calendars and sometimes respond to the fundraising requests, but even if I never looked at one again, I’d know an important Jewish holiday was coming by the matzo display in my local supermarket.

I used to live in Manhattan, which is a Jewish city. You never had to worry about finding a decent bagel—boiled, not baked—or real belly lox—not Nova smoked salmon. There are some suburbs near the city where I live now that have large Jewish populations and I’m sure you can find real Jewish food there, but I live in the downtown core where the selection is far more limited. Look at the supermarket shelves and you’ll quickly understand the ethnic breakdown: lots of pastas and sauces speak to the Italian influence. Foods that reflect the tastes of a large Latin American population increasingly dominate shelf space; I’ve become a convert to strong imported coffees, chickpeas, and Goya-brand cookies, as well as some Indian delicacies. A display of Halal meats indicates the importance of the growing Muslim community. But of Jewish food there’s not so much. You can find some Seasons sardines and Kedem juices and Manischewitz soups, but beyond them not much. Unless, of course, you count the matzo.

I’m not a big matzo fan and usually don’t eat more than a small piece at the first Seder, but I understand why my more observant friends joke that it is the bread of affliction. It’s not a staple of my diet throughout the year, but when my local supermarket sets out an attractive display of different varieties of matzo—egg, and whole wheat, chocolate, and more—I know a holiday is coming. And not just Passover. They celebrate Rosh Hashanah and Chanukah and I wouldn’t be surprised to find them on display to remind us that Purim or Shemini Atzeret is upon us. I often want to ask the manager if he thinks Jews eat matzos three meals a day, every day, but I save my time with him to argue about expired coupons. And although it’s easy to make fun of this misconception of what Jews eat on our holidays, at the end of the day, it’s very well intentioned on the part of the folks who manage my local supermarket, some of whom probably have very little interaction with Jews outside of their work life. That’s why, in addition to my Puerto Rican coffee and Italian anchovies, my Indian paneer and British water biscuits, I’ll be stocking up for the new year by purchasing a fresh box of matzos.

After retiring from a career in public relations, Kathryn Bloom went back to school and received a PhD in literature from Northeastern University in 2018. She now teaches at several Boston-area institutions and writes critical articles and essays for a variety of publications.

- No Comments

September 13, 2019 by Eleanor J. Bader

The Relevance of Grace Paley in the Trump Era

In the late spring of 2016, writer Judith Arcana began to reckon with the probability of Donald J. Trump ascending to the US presidency. “As I watched the emergence of Brexit in the United Kingdom, I was electrified,” Arcana told Lilith’s Eleanor J. Bader in mid-August. “I understood how—and why—Donald Trump could become president.”

This conclusion frightened her; nonetheless, Arcana found solace in thinking about activist-writer Grace Paley (1922-2007), the subject of her 1993 biography, Grace Paley’s Life Stories. “Grace’s life is a model for us right now, in the streets and on the page,” Arcana wrote in the Preface to the recently-released second edition of the book (Eberhardt Press).

Indeed, it’s impossible to read Grace Paley’s Life Stories and not be inspired by her energy, optimism, and fortitude. Add in her literary output—essays, poems, and three short fiction collections—The Little Disturbances of Man (1959); Enormous Changes at the Last Minute (1975), and Later the Same Day (1985)—stories that showcase the everyday interactions of working-class men, women, and children, and it is clear why Paley’s work remains relevant years after her death.

- No Comments

September 11, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

South America’s Jewish Prostitutes (Sex Slaves, Really)

It was shocking—and horrifying—to learn that more 100,000 Jewish women from Eastern Europe had been forced into sexual slavery in South America by other Jews willing and eager to exploit them. Talia Carner’s new novel, The Third Daughter (HarperCollins) dramatizes this disgraceful chapter in Jewish history, and she talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the very contemporary impact this story continues to have.

YZM: How did you come to this subject?

TC: I had first become aware of the magnitude of global and historical sexual exploitation at the 1995 International Women’s Conference in Beijing. An aging Filipina with an operatic voice cried to high heavens about her enslavement by the Imperial Japanese Army during WWII as one of thousands of girls and women captured in the Pacific Rim. Then a teenager, she had been imprisoned in a “comfort station” to serve the soldiers’ sexual needs.

The plight of kidnapped women forced into sexual slavery touched me deeply, and in my head it was narrated by the Filipina’s haunting voice. In subsequent years I read about sex trafficking and attended presentations by UN-affiliated NGO’s in New York City, where I live.

A snippet of the history of girl victims lured from beleaguered Eastern European Jewish communities to South America had come to my attention through Hebrew literature. My interest was reawakened when I stumbled upon a short story by Sholem Aleichem, “The Man from Buenos Aires,” (now in my own translation on my website). I googled the subject and was appalled to learn how much information was hiding in plain sight about Zwi Migdal, the legal trafficking union. Yet, the estimated 150,000 to 220,000 Jewish women exploited by its members had been forgotten, lost in the goo of history.

- 1 Comment

September 10, 2019 by Chanel Dubofsky

Why Molly Wernick is an Advocate for the Separation of Church and State

By Chanel Dubofsky

When Justice Anthony Kennedy announced his retirement from the US Supreme Court in June 2018, fear, panic, and dread rose up in the throats of pro-choice Americans. The precarious position of Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision protecting a person’s choice to have an abortion, was one that people had been well aware of since before the election of Donald Trump in November 2016, but Kennedy’s retirement provided the opportunity to appoint another anti-choice justice who could eviscerate Roe if and when the time came.

For Molly Wernick, who oversees Community Engagement initiatives for Habonim Dror Camp Galil in Southeastern Pennsylvania, the appointment of Brett Kavanaugh, Trump’s choice to replace Kennedy, meant the transformation of abortion debate, from “something that didn’t threaten my life and future to something that did.” Her response came in the form of an article for Medium, written the second day of Rosh Hashanah 2018, in which she wrote about learning that she and her husband were both carriers of Tay Sachs disease, an inherited, degenerative condition which leads to death in children, typically by about the age of four. In a post-Roe America, Wernick reflects, she, as a person of privilege, would be able to access an abortion, which isn’t the case for many others. As a result of the article, Wernick told Lilith, people came forward to tell their stories of abortion and miscarriage, stories they had kept secret until then, out of a sense of shame.

But there’s another element to the abortion rights conversation, and that has to do with the separation of church and state. “It’s also a slap in the face to my own religious freedom,” says Wernick. While the Christian belief that life begins at conception controls the anti-choice actions leading to abortion legislation, Wernick points out that that’s not what the Jewish view of abortion is. “For the first 40 days of gestation, a fetus is considered “mere fluid” (Talmud Yevamot 69b), and the fetus is regarded as part of the mother for the duration of the pregnancy,” wrote Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg, on Twitter in May 2019. (Read the entire thread, it’s a great 101 on Judaism and abortion.) Restricting, and attempting to ban legal abortion altogether on the basis of Christian interpretation, explicitly violates the First Amendment, which protects freedom of religion.

“Someone else’s religious doctrine is impacting my life and how I plan my family,” says Wernick “I can’t believe Jewish communities are staying silent.”

Let’s be clear: individual Jews, as well as certain Jewish organization like the National Council of Jewish Women, have spoken, and continue to, speak out against proposed bans of all abortions after six weeks of pregnancy (which are in effect total abortion bans, since many people who can get pregnant may not even know they are pregnant at six weeks), and other anti-choice legislations. Where, wonders Wernick, is the Federation movement, which was founded on the premise of protecting Jews from forces wishing to violate the separation of church and state? What can be done to stop Christian lawmakers from acting upon Jewish bodies?

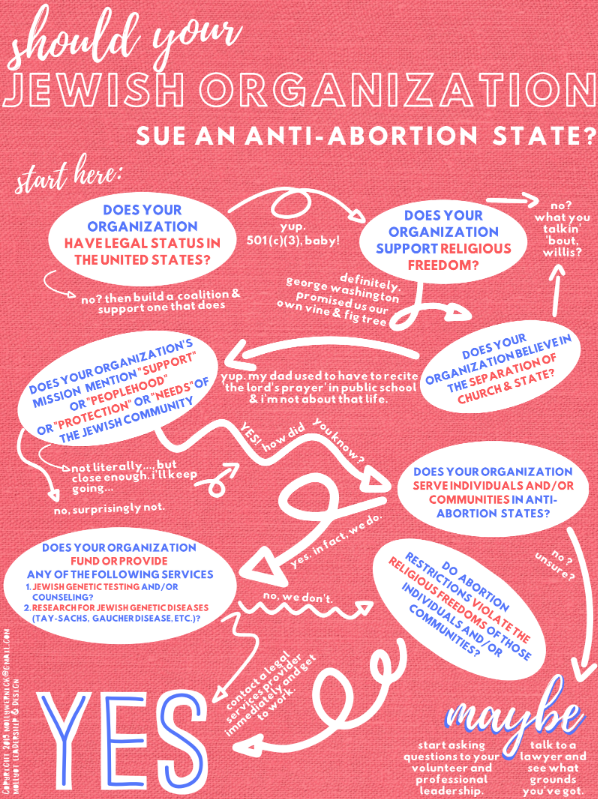

Wernick has done a lot of thinking and strategizing around potential legal recourses, and she has created a graphic depicting the steps Jewish organizations can take to address this direct violation of religious freedom. For example: a court case could be brought by a Jewish organization seeking to support a member who has had their religious freedom violated by not being able to access abortion care. In order for this to happen, however, a person would have to know that her rights are being violated––so familiarize yourself with the abortion laws in your state, as well as those that dictate access to contraception. (Do you live in a place where pharmacists can refuse to fill your birth control prescription based on their religious beliefs?) One also needs to have access to a Jewish organization willing to take action, even if that means the organization may risk losing donors or congregants. Ironically, Wernick might turn out to be the ideal person to bring a case based on religious freedom, since she may one day find herself terminating a pregnancy because of Tay-Sachs. “It’s the only silver lining,” she says.

Want to take action now? Familiarize yourself with the abortion laws in your state, and what it would take to access an abortion: distance, cost, time off from work, and more. T get further acquainted with what Jewish law says about abortion, check out Danya Ruttenberg’s Twitter thread, as well as My Jewish Learning. How do your state and local representatives vote on abortion, and how will that affect how you vote? “We need to remind representatives that they actually work for us,” says Wernick. And finally, remember that change requires mobilization, so talk to your friends and family and use that collective energy to make an impact.

- No Comments

September 6, 2019 by admin

Supporting Social Entrepreneurs

By Jamie Allen Black, CEO, Jewish Women’s Foundation of New York

When Tamar Menasseh grew frustrated with the gun violence ripping apart her neighborhood on Chicago’s Southside, she did not pack up and move. Instead, she pitched a lawn chair, set up a bar-b-que, and invited neighbors to join her for a meal. After her model of community gatherings helped to lower tensions it evolved into Mothers Against Senseless Killings, which has outposts in several states, including on Staten Island, N.Y.

The sexual assaults Evie Litwok witnessed as an inmate in two federal prisons gave her purpose upon her release. Today, Litwok runs Witness to Mass Incarceration, an organization that was commissioned by the U.S. Department of Justice to investigate sexual violence against incarcerated LBQT+ women and provides people just released from prison with suitcases filled with basic supplies to help them get started on the outside.

While we can only speculate about whether the world would be a better place if women were in charge, what is clear is that many women are adept at turning their personal experiences into unique professional ventures. Based on our 20-plus years of experience funding women-led organizations, The Jewish Women’s Foundation of New York knows that not only could women solve some of the most intractable problems around the globe, but that more attention – and funds – must be designated to make these efforts successful.

- No Comments

September 5, 2019 by Nora Lee Mandel

Does Leonard Cohen Embody Jewish Men’s Fantasy Fulfillment? An Exhibition and Documentary Film Provide Clues

By Nora Lee Mandel

When Canadian poet and singer/songwriter Leonard Cohen died November 7, 2016 at 82, eulogies reverberated with “mystical,” “mysterious,” and “celestial.” A new documentary, Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love (Roadside Attractions), and the exhibition Leonard Cohen: A Crack in Everything, up until September 8 at New York’s Jewish Museum, demonstrate that Cohen, like so many male artists of his and previous generations, fit a pattern of an archetypal Jewish men’s fantasy fulfillment. His muse, Norwegian Marianne Ihlen, was a blonde gentile goddess; a disparaging Yiddish word for the type is no longer PC.

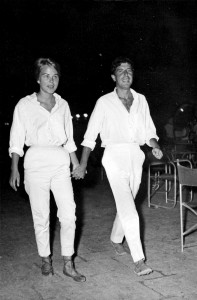

Photo of Marianne Ihlen and Leonard Cohen from the film, “Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love.” Courtesy of Roadside Attractions.

Iconoclastic as he was, Cohen fit the pattern. Irving Berlin was inspired by fair-haired socialite Ellin Mackay to pen “Always” in the 1920s, and more love songs after they married. In the 1960s, Marilyn Monroe posthumously influenced her husband, Arthur Miller to write After the Fall. Diane Keaton was Woody Allen’s icon of golden non-Jewish women in Annie Hall and other 1970s films. This trope is so familiar that Albert Brooks satirized Sharon Stone as The Muse (1999) with flaxen tresses.

For the new Leonard Cohen film, director Nick Broomfield rediscovered home-movie-like footage from the 1960s by the late documentarian D.A. Pennebaker, where Marianne smiles, sails, and swims off the Aegean island of Hydra: “The sun bleached my hair, so in Greece I was very blonde…Leonard did the writing. I ran and did the shopping and brought food. I was his Greek muse, who sat at his feet. He was the creative one…I would say ‘I am an artist. Love is an art’. I was living.” After the luminescent Judy Collins initiated his performing career, Cohen’s road manager and record producer chuckle at how audiences seemed mostly women, particularly blondes, and that Cohen relayed them to his hotel room.

- No Comments

August 30, 2019 by Arielle Silver-Willner

Does Judaism Permit Abortion? Depends Who You Ask.

By Arielle Silver-Willner

Recent threats to abortion access in the U.S. have provoked national discourse regarding reproductive justice–What does it mean? Whom does it affect? How can it be implemented? These questions have extended to Jewish communities, and create the opportunity for lively, comprehensive discussions.

Addressing both Jewish tradition and the current sociopolitical climate, the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance (JOFA) hosted a panel this July in Manhattan to address these questions among others. In Orthodox communities, the subject of reproduction is often governed by the halachic law, which instructs Jews to “be fruitful and multiply.” Thus, contraception and abortion are somewhat contentious subjects. However, the JOFA panelists– professor of Judaic Studies Dr. Elana Stein Hain, lawyer Gail Katz, and ObGyn Dr. Susan Lobel– seemed to agree that, at the very least, safe and legal abortion should be available if the pregnant person’s life is at risk. Stein Hain explained that Jewish texts declare the pregnant woman’s life “takes precedence over the life of the fetus.” Thus, clearly, Judaism does accept the termination of a pregnancy in certain circumstances. What these circumstances are, however, is less clear. Laughing, Stein Hain noted, “in true Jewish fashion, [it] depends who you ask.”

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...