The Lilith Blog

October 13, 2019 by admin

Trash to Treasure

by Anna Sacks

In my dreams, I’m constantly sorting trash. “Waste” is my inescapable obsession and addiction.

Three years ago, I left my job at an investment bank in Manhattan for a Jewish farming fellowship in rural Connecticut. Burned out, I found in the fellowship what my job lacked: time outdoors, spirituality, intentional community, and physical labor.

Adamah

One of The Adamah Fellowship’s chores, which I loved in theory but hated in practice, was to pull wheelbarrows filled with food scraps up a hill to the chickens’ enclosure. There, our chickens feasted on our scraps, then laid eggs for our consumption. Whatever scraps they didn’t eat would–by the invisible magic of fungi, bacteria, and invertebrates (FBI for short)–turn into compost, which is like Redbull for soil, but healthier. We’d then use the compost, as opposed to commercial fertilizer, on our regenerative farm to grow more food.

- No Comments

October 10, 2019 by admin

Turning Sukkot Inside Out

by Shoshana Lovett-Graff

When I first moved into my third-floor apartment, I lamented my lack of a backyard. The concept that I would not have access to the earth, even the crumbling, gravel-ridden soil of West Philly, seemed foreign to me, especially coming from Florida, where my former one-story home stubbornly squatted in the swampland surrounding it, dirt creeping up its walls and onto the window screens. I liked the idea of having a spot of land I could place a lawn chair on, where I could nestle beneath an elm tree and marvel at the shadows of buildings above me. The balcony sufficed, though the material beneath my feet was slightly corroded and paint chips occasionally floated down from the roof.

I sat on my balcony often, reading, eating, or talking with friends. The open sides kept me cool on warm nights and the roof, with a garland of lights wrapped around its interior frame, kept the rain and sun at bay. Though the balcony was connected to my apartment, it made me feel differentiated somehow. I felt more at ease, more pensive, when I sat on my folding chair and looked out on the street below.

- No Comments

October 8, 2019 by admin

Sweet Bites for the New Year

By Susan Barocas

One of my favorite sweets for as long as I can remember is baklava – flakey layers of buttery filo and crunchy nuts, all soaked through with a special honey-sugar syrup until each piece is heavy with gooey goodness. I think there must be some genetic imprinting from my Sephardic ancestors who spent centuries in the Ottoman Empire for me to love it as much as I do.

I’ve tried baklava in bakeries and restaurants all over the world. For my sister’s bat mitzvah many years ago, I came home from college and in one very long night made enough for 200 people. Years later, while waiting for my now 23-year-old son to be born, I filled the freezer with the sweet diamonds, each in an individual paper cup ready to celebrate his birth and brit.

Before, since and in between, I have made pans and pans of baklava, many of them for break-fasts because clearly syrup-soaked baklava is a perfect choice this meal. But, I have to admit that a few years ago I got tired of the baklava production. From working with the rapid-dry filo and the slow baking process to cutting the full pans of pastry without destroying the delicate layers and then the messiness of actually eating a piece, I was looking for a better way.

I found my answer in baklava bites, filling pre-made mini-cups of filo with chopped nuts followed by a quick bake and then a syrup bath before serving the two-bite treat to…well, I’ve made bites for 200 in under an hour! It’s so easy that I now make baklava just because, no special occasion needed. And no butter or oil brushed on every filo layer either, which lowers the fat content considerably.

I found my answer in baklava bites, filling pre-made mini-cups of filo with chopped nuts followed by a quick bake and then a syrup bath before serving the two-bite treat to…well, I’ve made bites for 200 in under an hour! It’s so easy that I now make baklava just because, no special occasion needed. And no butter or oil brushed on every filo layer either, which lowers the fat content considerably.

This week I’ll be bringing plenty of baklava bites to my friend’s break-fast so we can all enjoy the sweetness of the new year together.

BAKLAVA BITES

by Susan Barocas

- 1 cup walnuts, chopped

- ½ cup pistachios or pecans, chopped

- 1/4 cup sugar

- 1 teaspoon cinnamon

- 1/4 teaspoon ground cloves

- 30 mini filo shells*

Syrup

- 1/2 cup sugar

- 1/2 cup water

- 3/4 cup honey

- 1 tablespoon lemon juice

Preheat oven to 350 degrees. In a food processor, add nuts, sugar, cinnamon and cloves. Pulse until chopped into mostly small, but still pieces. The nuts won’t be even in size and that’s fine. Nuts can also be hand-chopped, then mixed in a bowl with the sugar, cinnamon and cloves until well blended.

Place shells on a baking sheet. Spoon about 1 teaspoon of nut mixture into each shell, mounding the mixture slightly. Bake 10-12 minutes just until the shells start to turn golden brown.

Make the syrup before making the bites or while they are baking. In a small saucepan over medium heat combine the water, sugar and honey and bring to boil. Reduce heat and simmer on low for about 15 minutes until the sauce thickens a bit. Stir in the lemon juice and remove the sauce from the heat. Either cool the syrup to room temperature and pour it over the hot bites, or let the bites cool while you make the syrup and pour the hot syrup over the cooled bites. Either way, pour at least a teaspoon of the syrup over the surface of each pastry, letting it soak down into the nuts. Serve immediately or within a couple hours.

Without the syrup, the unbaked bites can also be refrigerated for 2 days or frozen for future use. Put the unbaked bites flat in a container and refrigerate or freeze. If frozen, thaw the shells for about 30 minutes. From the freezer or refrigerator, bake the shells 10-12 minutes in a 350 degree oven and proceed as directed above. The syrup can be made ahead and refrigerated for up to 3 weeks. Warm to room temperature before pouring over the hot pastries.

*Available at Middle Eastern markets, some gourmet shops and online.

- No Comments

October 8, 2019 by admin

The Never-Ending Yom Kippur Loop

By Nessa Norich

I was commissioned to create a performance for Lab/Shul’s Storahtelling–a ritual modeled after the ancient practice of reading and interpreting the Torah as it’s being read. My role as a Maven is to relate the Yom Kippur Torah reading, Leviticus 16, to our times. Here is an excerpt from my upcoming Yom Kippur performance.

Photo Credit: Tucker Mitchell

Today, we have the privilege to gather, hundreds of us within the richness and complexity of our community, in order to turn inwardand listen for what needs healing. The Torah reading today, Leviticus 16, reads like an ancient instruction manual for how to atone “for eternity.” We have listened to it for millennia as part of our yearly healing practice.

Today, I am listening for what this chapter has to teach us about healing from an ancient Jewish perspective, because I want to understand how we, as Jews, have learned to heal. I want to take stock of what healing means for us now, with thousands of years of survival behind us. Because what’s the point of showing up, if you don’t really know what you’re doing here?

- No Comments

October 4, 2019 by Roberta Elliott

The Gift of Census

There has been much talk recently of the 2020 U.S. census. Those on the right want it to include a citizenship question; those on the left do not. In the same month that the President issued an executive order about the census, the Torah chimed in with one of several yearly reminders of the importance of census taking. The Torah portion Pinchas begins with a huge census, a seemingly endless list of all the clans that are readying themselves for war with the Midianites. A list of names that we read to this day.

At its most elemental, a census is no more than that – a list of names. Since antiquity, it has provided a much-needed organizing principle for society, serving an array of purposes from the merely administrative to the political to the nefarious. Of the last, I am thinking of the Germans as they plotted and succeeded in extinguishing the light of European Jewish life. They were great list makers. They listed the names of those they murdered and they listed the names of those they were about to kill.

In 1938, my father, Franz Engel, was living in his native Vienna and witnessed the Anschluss, the annexation of Austria by the Nazis. According to family lore, a “friendly” SS officer tipped him off that my family’s name was on the deportation list. As my father told the story, he locked himself in his room for three weeks to devise a plan to get his parents and sister out safely. Ultimately he did so, but at a price. The wound of being ripped from his homeland informed the rest of his life and was part of my inheritance.

- No Comments

October 2, 2019 by admin

Reflections on the Gender-Inclusive Siddur

By Eve Romm

I recently spent a Shabbat morning at Havurat Shalom, a small lay-led congregation in Somerville, Massachusetts founded in 1968 as part of the neo-Hasidic movement. I knew from the Hav’s website that their prayer book features “Hebrew and English gender egalitarian language for both God and humans,” but I wasn’t sure quite what this would mean in practice. Opening Siddur Birkat Shalom, a spiral bound volume with a blue cover, I was surprised by the sheer thoroughness and rigor of the adaptations. Not only pronouns but verb forms, adjectives, possessives and plural nouns had been expertly shifted with flawless Hebrew grammar. In addition to alternating between masculine and feminine language for God, the siddur had altered much of the language about God’s sovereignty in the traditional liturgy. The liturgical poem, Adon Olam, for example, opened with the words “source of the world who dwells…” (eden olam asher shakhna) rather than “lord of the world who rules…”. Some remained: I particularly relished the phrase “hamalka hayoshevet al kisei ram v’nisa”, “the queen who sits on a lofty and glorious throne,” which marked the transition into the main body of the morning service.

As services began, I noticed my own resistance to these changes, at the same time as my inner grammarian inspected the unfamiliar feminine forms with interest. Having come to traditional observance as an adult and taken pains to become familiar with the Hebrew liturgy, it was hard to surrender my mastery of the text and stumble over pronunciation again. Perhaps at a deeper level, having struggled with the place of women in traditional Jewish texts and communities, I was reluctant to let my guard down enough to trust a more inclusive liturgy. A lot of what I value about the Jewish tradition is the opportunity it furnishes to come into close contact with texts which are often difficult or alienating. Instead of simply rejecting the parts of the text which may wound the contemporary reader, a commitment to Jewish life means remaining in dynamic conversation with a tradition which can be at the same time sam mavet, poison, or sam hayim, life-giving elixir.

However, my brief foray into the gender-egalitarian siddur made me question my assumption that being a woman who is serious about Jewish practice and the study of Jewish texts means ceaseless wrestling with the deeply patriarchal structure of the Jewish tradition. Interestingly, though Havurat Shalom’s approach is to be exhaustively thorough in its adaptation of the liturgy to include feminine and non-hierarchical language for God, they do not alter the text of the Torah reading in this way. To my mind, this difference reflects a crucial distinction between study and prayer.

Rigorous study means serious engagement with the ways in which the text pushes the reader away and resists easy incorporation into modern life. Its goal is to understand the tradition on its own terms, and it requires a kind of interpretive resilience, a tricky separation of personal injury from scholarly interest. Prayer is not like this. The texts with which we pray, I have come to believe, should serve as a verbal technology for spiritual connection, allowing us to enter into them with relative ease so that they can be used to encounter the divine. To alter the text of the liturgy is not to censor it, it is to refine its power as a tool of worship in a particular time and place.

It is also a kind of theology in action. As the inheritors of an incredibly rich textual tradition, many Jews have learned to imagine God primarily through language. The frequent occurrence of certain names of God — Adonai tz’vaot (Lord of hosts), av harahaman (compassionate Father), eloheinu v’elohey avoteinu (our God and the God of our fathers), and melech haolam (King of the universe), to give only a few examples — certainly shaped my personal theology, although intellectually I resist their implications of a stern, masculine, God-as-judge. To a much greater extent than I had expected, even a brief experiment in using different language — makor hahayim (source of life), eden olamim (origin of the universe), shechinah (Presence), imah (Mother) — helped me to see my own gendered assumptions about God more clearly, and to begin to surrender them.

The goal of this adaptation of the liturgy, in my mind, is not that we come to think of God as primarily feminine. Instead, it is that we develop a deeply flexible and multifaceted theology, which embraces God’s ineffability more authentically and completely than the pre-modern rabbis who compiled the text of the siddur (prayer book) were perhaps able to do, being limited, as we all are, by their time. Those who resist this approach to the text of prayer often express concern that even small revisions are dangerous, potentially leading to the elimination of any part of the traditional language that might be objectionable, and losing much of what makes this ancient tradition compelling and complex in this process. I share this concern, but I am also concerned that without the willingness to, cautiously and responsibility, shape and reshape the practice of Jewish prayer, it will cease to be a source of life, joy, and meaning and become a burdensome rote observance. Our centuries-old tradition is not fragile enough to be damaged by this approach — on the contrary, diversity of practice has always made Judaism more resilient and flexible, more deeply adequate to the lived questions of its adherents, and more expansive in terms of who is able to find shelter under its canopy of peace.

Eve Romm recently finished her undergraduate studies in comparative literature and literary translation at Yale University. Her interests range from baking to Talmud study, and she’s particularly passionate about Yiddish women’s literature, the politics of Bible interpretation and translation, and the history of the book. She’s currently living in Somerville, teaching Hebrew school, and working as a freelance writer.

- No Comments

September 29, 2019 by admin

Striking For the Climate, Praying With My Feet

By Laura Mandelberg

On Friday, Sept 20th, I danced and chanted and marched with thousands of other people at the Climate Strike in downtown Boston, as part of a worldwide day of action in which over 4 million people took part. We were striking because scientists tell us that we have less than 11 years to radically remake our society in order to prevent the worst of climate catastrophe, yet our leaders have failed to take action at anywhere near necessary scale; because the climate crisis is an issue of racial, gender, and economic justice; and because, most simply, we want to have a livable future.

On Friday, Sept 20th, I danced and chanted and marched with thousands of other people at the Climate Strike in downtown Boston, as part of a worldwide day of action in which over 4 million people took part. We were striking because scientists tell us that we have less than 11 years to radically remake our society in order to prevent the worst of climate catastrophe, yet our leaders have failed to take action at anywhere near necessary scale; because the climate crisis is an issue of racial, gender, and economic justice; and because, most simply, we want to have a livable future.

City Hall Plaza was filled with strikers of all ages, from infants to octogenarians, Gen X-ers to high school students with signs referencing the latest memes. After a program of powerful speakers and a short dance break, we marched to the State House, where a smaller group held a sit-in.

This is how I live out my Jewish values. This is how, in the words of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, I pray with my feet.

- No Comments

September 27, 2019 by Joan Roth

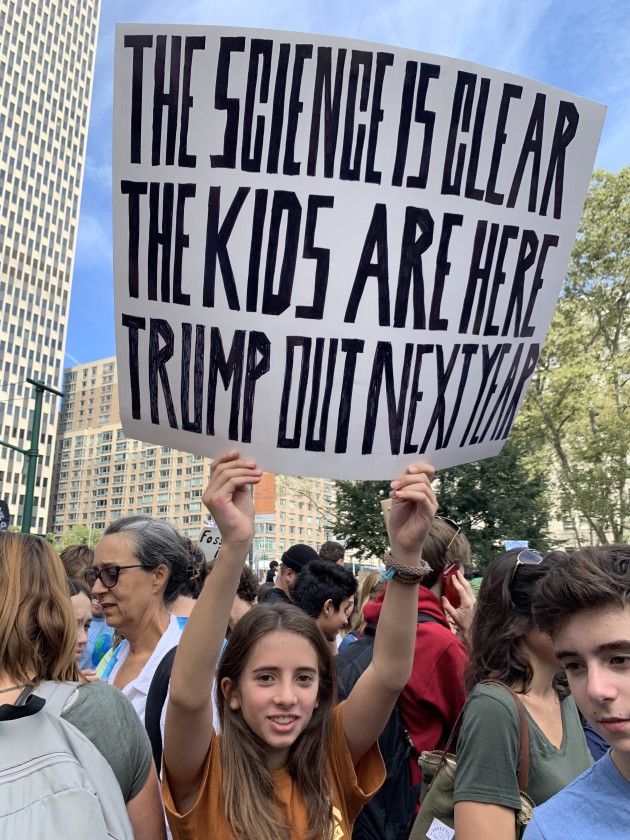

Striking for the Climate: A Photo Essay

On Friday, September 20, 2019, 16-year-old Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg, sparked historic protests. Revolutionary students- school kids- walked out of their classrooms to raise awareness about the environmental hazards (emits carbon dioxide) and health risks (pollutants) associated with burning fossil fuels, as well as, most importantly, its irreversible consequences of global warming. In over 150 countries, millions of global citizens marched in solidarity behind the moral clarity of its youth, demanding world leaders transition to renewable energy,

In New York City alone, tens of thousands of students, teachers and parents joined the People’s Climate Movement on this hot September day in lower Manhattan, down Broadway, from Foley Square by the courthouses, to Battery Park at the southern tip of the Island. They faced New York’s harbor with handmade signs, advocating for global action/legislation to stop global warming and prevent climate change.

With an unusual sense of urgency, young performers, facing the crisis of their lifetime and politicians unwillingness to do anything about it, sang, danced and spoke out with gusto. At the close of the rally, Greta Thunberg, who at 15 took time off school to demonstrate outside the Swedish parliament in Fridays, appeared onstage bearing the now-iconic hand drawn sign calling for stronger climate action, the sign which galvanized a school climate strike movement under the name, Fridays for Future.

“This could only be a fantasy,” she said, alluding to the fact, it was only one year ago that she began her simple school strike for climate change, wondering if it might catch on someday. “But,” she says, “I never believed it would happen so fast, in few months! We will not give up!”

Joan Roth

Joan Roth

Joan Roth

Joan Roth

Joan Roth

Joan Roth

- No Comments

September 26, 2019 by admin

Finding a Spiritual Home in the Woods

by Karen Bloom

My husband Ira and I are heading down a trail in Harriman State Park, just north of the city. The setting sun’s orange light reflects against and highlights the surrounding foliage. Everything is aglow during this magical time of day. We have been hiking since morning, as we do once a week year round. It is early September and I ask Ira about going to Rosh Hashanah services at Temple Israel of New Rochelle that next week. He is not enthusiastic, sweeping his hand across the trail in front of us — “this mountain is my spiritual place”. Soon after, an idea takes root.

Truth be told, we like going to services, just not on the high holidays. It is way too crowded and it feels confining sitting indoors for long periods of time, especially on crisp fall days. As much as I have tried over the years, I get antsy, focusing on the people sitting around me more than on the prayer books before me. How right is Ira…our spiritual home is in the woods.

- No Comments

September 23, 2019 by Elana Rebitzer

Russian, Music, Puppetry, and Dance: My Babushka in Translation

In Бабушка | BAb(oo)shka, playwright and performer Anna Lublina centers her Russian-speaking grandmother’s stories. In this new play at the 14th Street Y, Lublina translates her grandmother’s stories not only to English, but also to gibberish, klezmer music, and puppetry. She talks to Lilith Intern Elana Rebitzer about the role of gender and translation in her work and how this play has affected her relationship with her grandmother.

Photo Credit: Teddy Wolff

Elana Rebitzer: Why did you choose to center the play with your grandmother’s story?

Anna Lublina: The performance grew organically out of my grandmother’s stories. Or, really, my different understandings of them. Every holiday, we’d get in a heated discussion around what it means to be Jewish. These conversations were hard but also fascinating! I started to think about how her experience of Jewishness informs yet dramatically differs from my own. How has her lived experience been altered as in the process of being passed down to me? I made this show to honor and explore those alterations.

ER: The story comes alive in so many ways– puppetry, klezmer, gibberish, Russian, and English. What led you to use all these different expressive methods to tell your story?

AL: When I began thinking about this show two years ago, I came up with this concept of “queer translation.” With queer translation, I wanted to focus on the “mis” part of miscommunication. I wanted to honor the negative spaces in stories. This idea got me thinking about my multidisciplinary theater practice….how you lose something moving from live dance to puppeted object, but those losses are so beautiful. Over this past year of building this piece, I wanted to explore all these different types of multidisciplinary translation. One example is a performance where three non-Russian speaking actresses attempt to translate audio of my Babushka speaking in Russian into a strange Russianesque gibberish. In that show, we were thinking about translating affect and emotional landscape behind a story. In another iteration, we translated the stories into a video game puppet show inspired by the SIMS. I really want to privilege different elements of the stories– the emotionality, the iconography, the political symbols, the structure of the narrative, etc— in different ways so we can experience how each translation is both flawed AND expanded.

ER: How do each of those languages / mediums change your grandmother’s story?

AL: Each translation is an attempt towards understanding. As I translate the stories into English, music, puppetry, dance, I am communicating (to you, the audience, and to my Babushka) what it is that I am understanding when she tells me her story. My interpretation often has nothing to do with her intention, and that’s the point! That’s what happens when we communicate. So in BAb(oo)shka, the story changes with each retelling to honor a different element of the story that I’m understanding: the pain of being an other, the pride of being an other, my babushka’s intense love and fear about this oppression occurring again, and a lot of anger. It’s really just built on the idea that when you share a story—whether in the kitchen or on a stage—you are giving it over to other individual subjectivities to shape and warp.

Photo Credit: Teddy Wolff

ER: What do you think are some of the ways that translation interacts with gender and Judaism?

In a lot of ways, this is where the performance originates. I have always felt that I have inherited my Soviet’ family’s sense of Judaism—an ethnic one—incorrectly. What I mean is that I don’t totally take on their version of Judaism. Instead of seeing myself as an ethnic or zionist Jew, I approach Judaism as an ethical practice and spiritual way of living in the world. So this arrival at another interpretation of Judaism—that’s translation in action. I see Judaism as expanding and evolving constantly, translating into new forms whenever it encounters new contexts.

I think gender has a similar evolution. My sense of my gender has been immensely shaped by my context. Although, I’d say my Babushka and I have fewer moments of mistranslation when it comes to gender. She is incredibly supportive of me as a queer person, and I think we find common ground when we talk about being “strong women.” So in a way, gender is more easily translated between us than Judaism.

ER: Did creating this play change your relationship with your grandmother? How?

Photo Credit: Teddy Wolff

AL: Yes, it has forced us to collaborate, to really listen and communicate in ways that disrupt our traditional power dynamics. We worked on the performance at a residency in France this summer, and it was such a powerful thing to treat my family members like collaborators. Instead of assuming I knew my Babushka’s boundaries as a storyteller, I had to really listen to her in a whole new way. That process exponentially expanded my understanding of her life and how she became who she is today. And I think she had to expand her understanding of me. And we’re still in this process. It has created conflict, triggered larger traumas, and forced our entire family to think creatively, together. It’s been an experiment in communication that I am excited to see translated to the stage. I guess you’ll have to come witness the show to see where we landed.

Бабушка | BAb(oo)shka runs at the 14th Street Y from September 26 through October 5. Lilith Subscribers can use the code LILITH for $5 off tickets.

Elana Rebitzer is an intern at Lilith Magazine and a student at Barnard College.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...