The Lilith Blog

June 24, 2011 by Amy Stone

Missing Esther Broner

I’ve just come home from Esther Broner’s funeral.

E. M. Broner, center, leading a women's seder (New York Times)

Esther got the A-list of speakers at her funeral. It was the list she put together right after her beloved husband, Robert, died exactly one year and one day before her. (With those close to her describing her slowly succumbing to failing heart and lungs, I imagine her dying of a broken heart.)

Nephew, children and the famous feminists who were part of her feminist seders over the years – Iconic Feminists Gloria Steinam and Letty Cottin Pogrebin – along with writer Vivian Gornick, American-Israeli Knesset trouble maker Marcia Friedman, longtime local NBC anchor woman Carol Jenkins and daughter, rabbis from Esther Broner’s beloved B’nai Jeshurun Synagogue, and more, all crowded into the Plaza Jewish Community Chapel on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, a few blocks from her tiny apartment.

Her nephew hit just the right note on his “crazy New York aunt,” whom he was amazed to find was famous. His magic aunt, a witch, a good witch, with the great cackling laugh.

The women privileged to be in Esther’s feminist seder circle over going back to 1976 lovingly and gratefully told of her rituals created for them in hours of need.

Words of wisdom: Don’t let the facts get in the way of a good story line. Don’t brush away pamphleteers. Show them respect; take what they’re giving out.

The healing generosity of Esther: Letty telling how when she was totally overwhelmed with all she had taken on, Esther had her lie down, arms outstretched on a huge piece of butcher paper. Esther then outlined Letty’s body with a magic marker and used a feather to brush away the stress from the outlined body. She had Letty repeat three times, “I have boundaries; I can say no.” (Read Letty’s entire speech in the Forward.)

Vivian Gornick spoke of how when she was blocked in her writing, Esther told her to come over and bring two pages. She kept coming over every week with two more pages until the work was done.

Gloria, thin, serious in black, modestly putting her palms together in a Buddhist greeting of respect. She described her shared grief with Esther after the death of Marilyn French, author of The Women’s Room and their laughing over The New Yorker cartoon of a man with briefcase selling closure.

Memories of Esther’s supply of magic sparkling toy wands and feather rituals. The queen of ritual starting with “The Women’s Haggadah,” written with Naomi Nimrod and published in Ms. Magazine in 1977.

Appreciation of Esther as wife, mother, novelist, poet, fighter for good causes, and weaver of magic rituals.

I remember how surprised I was when I interviewed her for the Lilith article on Feminist Funerals, amazed that she seemingly hadn’t given thought to the final rituals of death. But once she got started, what visions. She wanted lamentations to return to funeral rituals. She imagined a chorus of women tracing the deceased’s matrilineage — “not just bereaved women quietly weeping in the front rows of the funeral parlor.”

Yes, that was what was missing. Letty quoted Esther as writing on a card shared with the Seder Sisters this year: “Esther Broner: Once she had a shadow. The shadow has been sheared off. Now there remains a trunk of memories of you.” Maybe that was her final hint of what a suitable ritual might be. If only the chorus of women had dug into the trunk other than verbally.

If only one woman had had the courage to give throat to the ululating cry of grief.

Surely the rest of us silent women would have had the courage to join in this ancient soul-searing sendoff.

- No Comments

June 14, 2011 by Naomi Danis

Sometimes We Say Hello

Cross-posted with United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism.

The diplomat uses as many words as possible and tries to say nothing; the picture book writer uses as few words as possible and tries to say everything, according to Uri Shulevitz, famed children’s author and illustrator.

The diplomat uses as many words as possible and tries to say nothing; the picture book writer uses as few words as possible and tries to say everything, according to Uri Shulevitz, famed children’s author and illustrator.

Perhaps Shulevitz was following in the footsteps of Rabbi Akiva, who famously said that the essence of the Torah is to love your neighbor like yourself. The rest is commentary. I, too, aspire to write in that tradition of few words.

Judye Groner, editor and co-founder of Karben Books, patiently and graciously corresponded with me about a manuscript I sent her in 2007, Don’t Eat Yet, Don’t Drink Yet. Part of an online writing challenge, the story was inspired by my own children’s experiences at the Forest Hills Jewish Center, in Forest Hills, New York, in the early 1980s, when they were very young.

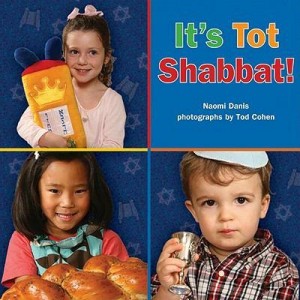

These excerpts from my emails to Judye are perhaps a commentary on (or a davening over) the 233 words that became It’s Tot Shabbat, my picture book, with photos by Tod Cohen, published by Karben in March 2011.

My notes reflect my concern not to make the introduction of religious experience merely the didactic conveying of rules. Like many Jews I am more interested in actions, in what we do or don’t do, and less interested in what people profess to believe. It is in this spirit that I do not mention God in the book. I don’t have a script for that conversation between parent and child, or child and parent, or child and child, certainly not one I comfortably can tell in the voice of a young child.

Every literary endeavor is an attempt to create some order and meaning out of the chaos of our experience, and perhaps the religious enterprise is acting on this same impulse. I wanted to make sure that the gentle but natural chaos of a child’s experience remains, that it isn’t erased by too much order. (more…)

- No Comments

June 13, 2011 by Susan Weidman Schneider

We Are What We Wear?

Cross-posted with eJewish Philanthropy.

We all have narratives we tell ourselves about clothes. The inherited fur you can’t wear and can’t part with; the dress from a landmark simcha, too fancy for Goodwill, too out of date for the resale shop; that ratty hoodie from Camp Ramah. And more. Please tell us your story on the Lilith blog. You know you’re not alone.

We all have narratives we tell ourselves about clothes. The inherited fur you can’t wear and can’t part with; the dress from a landmark simcha, too fancy for Goodwill, too out of date for the resale shop; that ratty hoodie from Camp Ramah. And more. Please tell us your story on the Lilith blog. You know you’re not alone.

Growing up, girls were supposed to be smart and look good. Or, at least appropriate. The being smart part had some flexibility, the looking good not so much. When I left Winnipeg for Brandeis, in the early 1960s, I sent ahead my trunk full of “appropriate” clothing, all with matching shoes and bags and gloves. Uh-Oh. Not so appropriate for the guitar-strumming, songs-of-social-protest-singing, Army-Navy-store-turtleneck-wearing cohort I discovered on that Waltham campus. Part of every story of social change can be told through our changing wardrobes.

Here’s a more recent story, from just a few months ago. I’m sitting in a Lilith salon at a college campus. About 15 Jewish women students are nibbling on hummus and pita and chewing over the state of the world. The evening’s conversation, which started out about mothers – taking off from a recent issue of Lilith magazine – quickly morphed into something else: What our clothes say about who we are and the people we choose to become. A woman in black pants and shirt gives her name, then remarks that she grew up in an Orthodox community where women dress in traditional, gender-specific, “modest” clothing. “When I started to wear pants, my mother got very worried. ‘If you’re not wearing a skirt, how will people know you’re Jewish?’” (more…)

- No Comments

June 1, 2011 by Merissa Nathan Gerson

There are Rules

http://evantravels.blogspot.com

There are rules, somewhere, about how to be a Chasid on an airplane. In that same rulebook there are most likely also a set of behavioral norms for a woman in stretch pants lying about in the back of the plane.

My leg started swelling on a flight to Budapest. I went to the flight attendant for ice and took to the empty row in the far back of the plane where I could elevate my knee. Sitting across the aisle was a swipe of off white and black stripes. A giant man in his late thirties with gorgeous greying peyot was davening in the back of the plane. When I walked by in my thigh defining outfit there was a protective whisk of the tallis.

I decided things; like he hated that I could see him pray. He was wearing a special tallis with silver adornments along the hem at the top. He was wrapped in tfillin, his head covered by his shawl. I was a bit jealous; I wanted to pray and get dressed up in costume to do it. And in addition, I felt evil. If he had seen me, and in my female secular glory no less, was I not the interruption to his prayer and piety?

I sat across and faced the window so I wouldn’t flash my naked knee as I iced it. I had my back to my Chassid friend and suddenly felt something on my neck. He was standing now, and whipping his tallis about, mostly striking my face and neck with the fringes. I thought it was a joke. Then I thought he had special ownership issues. Then I was angry, convinced he was purposefully tracing a tallis across my head to somehow purify me.

I don’t like being in confined public spaces with orthodox Jewish men because I don’t understand the boundary. I don’t know when I need to stop and protect their piety, or when I need to stand as I am. On the sherut to the airport a young yeshiva bucher got on last. All the seats were taken and he had to make his way to the back and squeeze between two women. All I could think was how this was assur, and how he would have to go to the mikvah to purify himself.

On the plane I whispered assur under my breath at one point, an ugly effort to shame my Jewish neighbor. I spent most of the flight, especially after taking measures to turn away from the praying man, frustrated and annoyed with being shunned and being touched by his tallis, his belly, etc., as he moved about freely. I resented his sense of entitlement. I resented, most of all, how mid prayer, tfillin at the forehead, he stared down the bodies of women walking past him en route to the bathroom. (more…)

- 3 Comments

May 31, 2011 by Liz Lawler

Chop Me Up For Spare Parts

So, here is a pop quiz: are Jews allowed to donate organs? Yes.

So, here is a pop quiz: are Jews allowed to donate organs? Yes.

I ask, because it turns out that many people are wrong on this count. Enough Jews are wrong about it, that Israel has been fighting off a bad reputation in the organ donor community. Frankly, it is simple playground etiquette—unless you are willing to share what is yours, do not expect to play with anyone else’s toys. It seems that even those Jews who refuse to donate their own organs, are willing to accept donations from others. Israel accepts far, far more organs than it donates, and the lack of reciprocity is leading to unpleasant consequences.

This came up when I first entered the conversion process. I guess because we were discussing death rituals and life cycles, and the treatment of a Jewish death. How does one die Jewishly? Timing matters–most Jewish leaders agree that the moment of death is when your brain stem stops functioning. Were you to be kept alive, it would be in a purely vegetative state. Not much good to yourself or others. But there is apparently a small segment of ultra-orthodox Jews who believe that you are only dead once your heart stops beating. But there’s the rub. Organs, to be useful to anyone on this side of the fence, need to be harvested within 12-24 hours of brain death.

So, while live donations are largely un-problematic, it seems that organs harvested from the dead are a slightly stickier question. But really, only in small measure. Across the denominational spectrum, Rabbis have broadly stated that it is a mitzvah to save a life, and have encouraged their congregations to sign off on donor cards. So it is doubly infuriating to come up against this tiny little segment of the religious population that seems to hold such sway in the Jewish imagination. Since when do we allow a small faction of zealots to tell us how to die and how to apportion our bodies once we do? As a woman, I bristle at any man who tells me what to do with my body, even in death.

There is a controversial bit of legislation that has been bouncing around Israeli parliament for while. The law would allow those Jews who sign an organ donor card to move up the list if they are waiting for an organ. It has met some resistance, but seems pretty equitable. The law’s stated intent is to prevent “free riders,” those who take more than they give. I think of this refusal as a kind of hoarding, and of this hoarding as a defense mechanism, a response to a history of desecrated burial grounds and inhuman mass graves. But it is a truncated and two-dimensional approach to the questions of life, death and the significance of human remains. These are the people who hide behind talk of “bodily desecration,” rather than take a more nuanced view of the donation process. It boggles my mind to think that you, a Jew, might not want to save another person’s life. Aren’t you commanded to do so? This is the BIG one, the overriding commandment, the one for which you can break all of the others. And for all of our history of violence, mayhem, and the scabs and wounds that we still nurse after the last century, those rules are what keep us human, and keep us bound as a group.

At the end of the day, I think that we all have an instinctive urge to say no. I just renewed my driver’s license. And that little box really gave me pause—“check yes or no if you want to be an organ donor.” My immediate response was, “what….? I’m not going to die…. Who have you been talking to??” It took a couple of breaths to face the question and remember that these organs are borrowed elements. No amount of clinging will allow me to hold on to this heart, these lungs, or these kidneys. So line up, hopefully it will be a while, but you can have them when I am done taking my turn.

- No Comments

May 31, 2011 by Maya Bernstein

Coda

Our family had returned from Israel. We had, eventually, embraced the mid-trip loss of our camera. We drew sketches of the special places we had been. We laughed and then sighed, without attempting to re-enact and re-capture the laughter for the camera. We returned home without pictures. We had moved on.

Our family had returned from Israel. We had, eventually, embraced the mid-trip loss of our camera. We drew sketches of the special places we had been. We laughed and then sighed, without attempting to re-enact and re-capture the laughter for the camera. We returned home without pictures. We had moved on.

And then we got the email. Our sister-in-law, who lives in Jerusalem, sent it, and included the whole chain of correspondence, originating with a random Israeli guy who was walking the streets of the Old City and had found our camera. He picked it up, flipped through the pictures, realized the camera must belong to a family on a trip, downloaded one of the pictures, and sent an email to his entire contact list, saying: “Sucks to lose a camera on a family trip. Does anyone recognize these guys?” His huge list of contacts forwarded it on to their huge list of contacts, and, in the fourth iteration, someone recognized my brother-in-law, and sent him an email, saying: “Hey, did you lose your camera in the old city?”

That is how it came to be that we have all of the pictures we took during the first week of our trip to Israel, and how it is that our camera, including the five-shekel piece my three-year-old had asked me to put in the front pocket of the camera case for safe-keeping, are en route across the world, heading home.

At first I was exuberant, lauding the positive uses of social media and a wide web of online “friendships,” joyously sharing the story as a model of the power of the kindness of strangers, the goodness of human nature, the beauty of the people of Israel. I downloaded the pictures with disbelief, sending them to friends and family, acknowledging the truth – I had accepted these were gone, but I am so happy to have them back!

But now I await the camera with breathless suspicion. Can it be that something you have accepted as gone, no longer part of your world, no longer a piece of your reality, can somehow resurface, intact? (more…)

- No Comments

May 31, 2011 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Caroline Leavitt on "Pictures of You"

Caroline Leavitt’s new novel—her ninth—starts off with a bang. Literally. Isabelle Stein is fleeing her Cape Cod home and husband after learning that not only has been cheating on her for the last five years, he’s about to father a child with his lover. Stricken and grieving, Isabelle piles her clothes and cameras—she’s a photographer, an identity that is central to the story—into her car and takes off. The day is foggy and even though she is driving well below the speed limit, her visibility is seriously impaired. Suddenly, through the fog she spies a car, facing the wrong way and stopped in the road. In front of the car stands a blonde woman in a red dress. Isabelle feels herself losing control of her car and as she does, she notices there is someone else there too—a boy—who sprints to safety. But the woman remains where she is despite Isabelle’s panicked shouting. Isabelle gets closer and closer; there’s no room to swerve, and she cannot stop. And then, “…the two cars slam together like a kiss.”

Caroline Leavitt’s new novel—her ninth—starts off with a bang. Literally. Isabelle Stein is fleeing her Cape Cod home and husband after learning that not only has been cheating on her for the last five years, he’s about to father a child with his lover. Stricken and grieving, Isabelle piles her clothes and cameras—she’s a photographer, an identity that is central to the story—into her car and takes off. The day is foggy and even though she is driving well below the speed limit, her visibility is seriously impaired. Suddenly, through the fog she spies a car, facing the wrong way and stopped in the road. In front of the car stands a blonde woman in a red dress. Isabelle feels herself losing control of her car and as she does, she notices there is someone else there too—a boy—who sprints to safety. But the woman remains where she is despite Isabelle’s panicked shouting. Isabelle gets closer and closer; there’s no room to swerve, and she cannot stop. And then, “…the two cars slam together like a kiss.”

“So begins “Pictures of You,” a powerful novel about love, responsibility, sin and atonement. In graceful, measured prose, Leavitt not only limns the outer lives of her characters, but delves deep into their hearts as well. What are some of the repercussions of this life altering—and in one case, life ending—collision? Lilith’s Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough asked Leavitt about this and other topics; their conversation is below.

“Pictures of You” deals with issues of moral responsibility, guilt and expiation. As you shaped and wrote the book, did these issues occur to you within a religious or spiritual framework? If so, can you elaborate?

They did occur to me in a spiritual way. I am a big believer in karma. I believe that there are forces in the universe that work with us or against us, and that really, we do reap what we put out there. I loved the idea of Sam [the boy Isabelle saw in the road] thinking Isabelle was an angel, and in a real sense, she was to him. She saves his life in so many ways, and perhaps that goes to the idea that people really can be angels, here on earth.

We know Isabelle was driving the car that killed April, so she is literally guilty, even though it was not her fault. But is she guilty in some more profound sense? Do you believe that she can—or did—atone for her crime?

I don’t really think she was guilty in that there was fog, and she did try to stop the car. But her guilt as in the sense of not taking advantage of all the gifts she had. She stayed in a town she hated. She stayed in a dead-end job. She wasn’t really running to something, which she should have done, as much as she is running away from her life. I don’t want to give away plot, but let’s just say she does atone for those things. What I can talk about is that as she cares for Sam, whom I believe she loves more than Charlie [Sam’s father and the widowed husband of April]–and she certainly does love Charlie–she cares for herself in some way. She opens up the world for Sam with photography, but she also opens up her own world by beginning to see the possibilities and the things that she can do.

Why did you wait to reveal that Isabelle was Jewish? What meaning does that have in terms of her character and the story as a whole?

I’m really spiritual and I love the idea of people coming to belief in their own way. I loved the story of Isabelle’s mother who in her time of grief became a born again Christian and loved the one man she felt would not die or leave her–Jesus. Isabelle is Jewish because Jewish people are often very introspective and they often feel guilty for all sorts of things–at least, that was the way it was in my family. Guilt plays such a large part in my novel, that it meant sense to me that Isabelle would be Jewish. I also, quite frankly, wanted to write about someone who felt like me about these matters, and that meant that I would have to make her Jewish.

What meaning, if any, did her mother’s conversion have for her? Did she embrace a new faith along with her mother or did she retain a sense of her Jewish identity?

Isabelle remained Jewish. She could understand why her mother wanted to be Christian (Jesus would never leave her or die on her), and although she likes the St. Christopher medal, it has nothing to do with belief for her. It is more something that can tie her to her mother. I don’t think Isabelle will ever give up her Jewish identity. It’s simply who she is.

A good portion of the book is taken up with the idea of angels—how they function, what they can—and cannot—do, what role they play in the lives of humans. Did you do much research about this? Did what you read or learned correspond with Jewish thinking and teaching on the subject? What is your own view about angels?

I did do research, which I found to be fascinating. When I discovered that the Hebrew word for angel is messenger, a chill ran through me. It fit perfectly! I even have Sam looking that up and seeing the definition. Sam believes Isabelle is an angel, who can get a message to his dead mother. I also loved that “angels give God distance.” That fit in perfectly with my whole theme of the yearning to connect, and never really knowing the ones we love, which in this case, includes God, doesn’t it? I do believe in God and I’m not sure about angels. However, I have an open mind. The more I read about quantum physics, actually, the more sure I am that anything is possible. Most physicists say that the universe is more incredible and far stranger than what we can imagine, and I love that.

- No Comments

May 25, 2011 by Merissa Nathan Gerson

Ba'al Tshuva

A ba’al tshuva friend suggested I read William Zinsser’s On Writing Well to help clean up my prose. I read it like bible roulette. Make a wish, close your eyes, and open to a random page. It works better with the bible because Torah is a better fortune-telling wisdom-yielder, but it still works. This week’s fortune a la Zinsser: “Get their voice and their taste into your ear – their attitude toward language. Don’t worry that by imitating them you’ll lose your own voice and your own identity.”

A ba’al tshuva friend suggested I read William Zinsser’s On Writing Well to help clean up my prose. I read it like bible roulette. Make a wish, close your eyes, and open to a random page. It works better with the bible because Torah is a better fortune-telling wisdom-yielder, but it still works. This week’s fortune a la Zinsser: “Get their voice and their taste into your ear – their attitude toward language. Don’t worry that by imitating them you’ll lose your own voice and your own identity.”

Ba’al tshuva means a person returning to the faith with fervor. It is a born-again Jew, a re-adhering human who decides to take the full religious plunge. I came to Israel a year ago, a mostly secular Jewess, with a thirst for Judaism. I attended Friday night services or Shabbat meals as a religion, and the rest, barring high holidays, fell by the wayside. In its place, I filled myself with yoga and meditation, Swami books and Hafiz poems, Khalil Gibran and others. I was a classic neo-Chasid, loving my mystical roots in Judaism and fearlessly informed by other religions.

I moved to Tel Aviv to teach English at the African Refugee Development Center. Besides teaching, everything else made me slightly miserable. This was not the Israel I remembered from living here as a kid, or visiting as a teenager. My own distaste surprised me as all I saw was a secular city aching for any opportunity to defy the confines of religion. I didn’t know a lot about Israel yet, like how this division between secular and religious is a defining factor in the country today. I just knew that religiously and spiritually—I was disappointed.

And then I somehow was ushered to Jerusalem. It was not an expected move. It was more as if there was some big hand, like in those claw arcade machines, and I was a stuffed animal, and someone in Jerusalem was winning the game. I moved to study Torah at the Pardes Institute for Jewish Studies and as my friend, Faith, explains, “You thought you were so open, but you were not as open as you thought.”

I was a post-denominational anti-establishment mystically leaning Jew enrolled in a strict text study program. I cried for nearly an entire month. For nearly half a year I took my tears to imply that I had defied gravity and was in the wrong place at the wrong time, like I had sold my soul. About nine months after my arrival I remembered what my rabbi, Rabbi Miles Krassen, then of Boulder, Colorado, once had said.

He told me a story of a woman whose steady flow of tears was a sign of her heart breaking back open, wide, and the tears were the trail back inside. Something like that, something you only hear in Boulder and only embrace, without cynicism, while living there. I thought I needed height. I thought I needed spirit and connection on a higher and ethereal plane and instead I was rooted and grounded and held by the warmest Jewish community.

Sure, it took time. I hated benching, I hated all the songs, I hated the blech and the halachic shaming. I still detest gender separate prayer, and abhorred the obligation and narrowness of everything. But it was that precise narrow obligatory Jewy core that restored a brokenness inside of me. I was cupped by a community of people whose beliefs did not echo my own, but whose devotion to being good people, G-d-fearing people and Jewish leaders was in step with my desires. We were an errant bunch, culturally mismatched despite being Jewish Americans, and yet linked by our separate relationships to the same core.

I didn’t know what a tractate was last year. I didn’t know how to read a Mishnah or who Ephron was and why buying property is complicated. I didn’t know that if you touch one edge of one sentence of Torah, it opens to a panoply of other complex sentences, perspectives, the voices of countless men, one after the other. I didn’t know how male dominated Torah scholarship had been, and how much it has evolved in recent years.

In a search for spiritual flight, I traded, without asking, for spiritual roots. I learned Jewish history this year, and modern Jewish thought. I learned about multiple modes of Jewish meditation practices, Jewish sex laws, and the inner writings of the Aish Kodesh. I spent sometimes more than nine hours a day learning, including evaluations of Tanach, of Chassidism, of Women and their obligations, or lack thereof, when it comes to mitzvot.

I was, in this process, terrified of losing my identity. I was worried about imitation, about Hebrew scholarship, about what would happen if I submitted to the rubric of religion. Somewhere in the middle something loosened in me. It was after I had to get over my arrogance, after I was humbled by low-Hebrew skills and minimal knowledge. Religious scholarship is a field in and of itself, and if I was the most Jewish of my secular friends in America, I became the least Jewish of a group of rabbis and educators and Jewish

leaders-to-be for a whole year. As they say, “It is better to be the tail of the lion than the head of the wolves.”

And so I let my attachment to ego go. Buddhism whittled its way in and I surrendered to Judaism. I koshered my kitchen. I began attending daily Mincha services. I stopped using my phone on Shabbos, and later my computer. I washed before I ate, kept laws like not cooking after sundown and waiting for three stars to appear to begin my week. I even did that old strange ritual where you jump towards the moon with an open hand, and watched bonfires sizzle en masse in Gan Sacher.

I imitated for a whole year and my fears of losing myself were never confirmed. As William Zinsser wrote, “Don’t worry that by imitating them you’ll lose your own identity. Soon enough you will shed those skins and become who you are supposed to become.” My identity returned, in full throttle. “My” Jewish, my way in Judaism is paved clear as day ahead of me. I am losing my devotional practice as my departure and return to America loom. I am disengaging my submission in order to survive in the secular world all over again. I am not scared, though. If I can leave myself for devotion, than I can also leave devotion for myself. Somehow, I am almost certain, devotion will return, and return, and return again.

- 6 Comments

May 16, 2011 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Jennifer Gilmore on "Something Red"

It’s the summer of 1979 and Sharon Goldstein, a professional caterer, is in her Washington, DC kitchen making dinner for her extended family. Her eldest child—Ben—is about to leave for his freshman year at Brandeis and his departure will no doubt reshape and reconfigure this family group. Sharon feels a mixture of excitement, nervousness and sorrow as she contemplates her son’s imminent departure. She takes great care in preparing the meal, thinking, “…it would be perfect to have the family sitting together in the backyard, all along the large communal table, the scuffed wood illuminated by lit candles and flickering torches, before Ben became a dot on the horizon and left the all behind.”

It’s the summer of 1979 and Sharon Goldstein, a professional caterer, is in her Washington, DC kitchen making dinner for her extended family. Her eldest child—Ben—is about to leave for his freshman year at Brandeis and his departure will no doubt reshape and reconfigure this family group. Sharon feels a mixture of excitement, nervousness and sorrow as she contemplates her son’s imminent departure. She takes great care in preparing the meal, thinking, “…it would be perfect to have the family sitting together in the backyard, all along the large communal table, the scuffed wood illuminated by lit candles and flickering torches, before Ben became a dot on the horizon and left the all behind.”

So begins Jennifer Gilmore’s second novel, Something Red (Scribner, $25), a provocative blending of the personal and the political. Lilith’s Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough interviewed Gilmore to get her take on, among other topics, life in the late 1970s, political ideologies as seen through the lens of character, Jews and food, Jews and weight and the execution of the Rosenbergs. Their conversation is below:

What drew you to the time period 1979-1980? Why did it feel essential to set the story at this particular moment? What is your own connection to that time?

A lot of people have asked me why I chose 1979, as I was alive, but quite young. There were lots of reasons I was drawn to it. I wanted to carry on the story of Jewish immigrants in this country (my last novel ends in the sixties), and what life was like for the subsequent generations whose issues were quite different than their parents and grandparents who came here. I was also very interested in the era for thematic reasons. It was the first time one country used food to starve another and I wanted to write about the way food played out in the family and then the way it played out it in the world. My father is an economist and foreign food policy was talked about a lot in our home–mostly at the dinner table–and the conflation of the personal and political struck me even then, though I wouldn’t have described it that way at the time.

And though it was a year I was too young to remember clearly, it was a seminal moment in history, fraught with endless fictional possibilities. Jimmy Carter was in the White House, the Iranian hostage crisis was in full bloom, there had been a nuclear accident at Three Mile Island. Disco was dying, (everyone but my grandfather was happy about this) and so was punk rock in its hardcore form, culminating with the death of Sid Vicious. Women’s oppression seemed to be waning, made concrete by Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party,” shown that year at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Culturally, the world was thriving: Styron’s Sophie’s Choice and Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song were released in 1979. So was Manhattan, The Rose, Apocalypse Now and Breaking Away. Then, on Christmas Day, Soviet deployment of its army into Afghanistan began. And on January 4, 1980, Carter announced the US grain embargo against the Soviet Union, which figures prominently in the book, and is when the novel begins.

Can you talk about the role of research in the writing of this novel? How you did it, and more importantly, how you kept it from showing? (more…)

- No Comments

May 16, 2011 by Merissa Nathan Gerson

I Was In Love With A Medicine Worker

I was in love with a medicine worker. We sat in the mountains at an outdoor café towards the end of my four-month trip to South Africa. We were sealed at that point, two hearts attempting to find a way to gracefully detach. During our meal a station wagon drove up and my mentor got out. I excused myself from my lover and took to my mentor, hugging and greeting him with great joy. This man had coached me in how to ingest South Africa, how to digest Apartheid, on how to determine the nutritional value therein.

I was in love with a medicine worker. We sat in the mountains at an outdoor café towards the end of my four-month trip to South Africa. We were sealed at that point, two hearts attempting to find a way to gracefully detach. During our meal a station wagon drove up and my mentor got out. I excused myself from my lover and took to my mentor, hugging and greeting him with great joy. This man had coached me in how to ingest South Africa, how to digest Apartheid, on how to determine the nutritional value therein.

I was an activist studying in Cape Town. The more I learned of multiculturalism and social change, as was the goal of my time there, the more my head split and my heart opened and my previous activism platforms felt hollow. This mentor sat with me on the fenced-in porch of a township community center as I cried, “How do you keep going?” The whole weekend we learned about keeping hope alive despite Cape Town’s secret underbelly, the unmarked graves, a city “drenched and built on blood.”

We visited the sites of massacre and of rebellion, a tour of history off the books. And we ended up behind a barbed wire fence for a Rosh Hashanah gathering, challahs hand-braided in Langa, song and prayer with a diverse group including former revolutionaries largely responsible, depending on whom you asked, for the fall of Apartheid. So when months later I saw this man who, despite his own wounds, like hating the one blonde girl in our group because “her eyes reminded him of his former jail guard,” I was overwhelmed and excited.

Everyone in Cape Town holds a story, and more than one story contradicts. I hugged my mentor goodbye and watched him get back into the car, the backseat of a Volvo, cap pulled down covering his eyes, as his wife drove him away. To me, an American thirsty to learn and know any history beyond my own, thirsty to rub up against the most prickly of South African history, to me, my mentor was a hero.

I walked back to my friend and he looked at me as if he had seen a ghost. “Why are you talking to that man?” He asked. “Do you know who that is?” (more…)

- 3 Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...