The Lilith Blog

March 1, 2012 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

A Conversation With Roberta Rich

Renowned throughout Venice for her gift at coaxing reluctant babies from the their mothers’ wombs, Hannah Levi, a Jewish midwife, is much in demand. But when she receives a summons from a wealthy Gentile count to attend his wife, she is torn about what to do. Does she defy Papal edict that forbids Jews from rendering medical treatment to Gentiles? Or does she try to alleviate the suffering of this unknown woman, and in so doing, earn the money to pay her husband’s ransom? These are the questions raised by “The Midwife of Venice,” the first novel by former lawyer Roberta Rich. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough had some questions of her own, and she sat down with author Rich to find out more about birthing practices in the 16th century, the transition from lawyer to novelist and what life was like in the Jewish ghetto of Venice.

Renowned throughout Venice for her gift at coaxing reluctant babies from the their mothers’ wombs, Hannah Levi, a Jewish midwife, is much in demand. But when she receives a summons from a wealthy Gentile count to attend his wife, she is torn about what to do. Does she defy Papal edict that forbids Jews from rendering medical treatment to Gentiles? Or does she try to alleviate the suffering of this unknown woman, and in so doing, earn the money to pay her husband’s ransom? These are the questions raised by “The Midwife of Venice,” the first novel by former lawyer Roberta Rich. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough had some questions of her own, and she sat down with author Rich to find out more about birthing practices in the 16th century, the transition from lawyer to novelist and what life was like in the Jewish ghetto of Venice.

What was the inspiration for this novel?

I have a very visual imagination. When I was in the museum in the Venetian Ghetto, I saw two things which ignited some images. The first was a shadai, or good luck amulet. I thought of the high infant mortality rate in those times, not just in the ghetto, of course, but all over 16th century Europe and had the idea for a shadai in the shape of a baby’s hand to hang over the cribs for protection. I also saw a pair of silver spoons resting in the glass display case. These crossed spoons became the inspiration for my heroine midwife to design forceps.

How did you conduct your research for it?

Fortunately, I love to read and do research although I must confess I am not a student of history and never took a history course beyond high school. However, there are a number of fascinating books written about Venice and the history of the Venetian ghetto. I was interested to learn that the ghetto was not only a place to sequester Jews, but it was also a relatively safe haven. In a scene from The Midwife of Venice, Hannah and her sister, Jessica, who has converted to Christianity and becomes a courtesan, accuses Hannah of being a ‘little ghetto mouse’, afraid of life. Hannah responds that the same gates that keep them in the ghetto, keep them safe. In fact, the Venetian government, the Council of Ten was protective of the Jews, valued them for their mercantile connections to the Levant (the Middle East) and for the high taxes and levies they were forced to pay for the ‘privilege’ of living in the ghetto.

- No Comments

February 21, 2012 by Elana Sztokman

Abortion in Israel, Contraception in the U.S.

Updated May 1, 2012.

It has been over 50 years since American women have had birth control pills to help manage fertility and family planning, yet it seems that the battle for women’s body autonomy is still not over. Just when we think that the future looks bright, that there are medical advances and widespread educational programs for consciousness-raising, some movement from the ultra-conservative Right emerges and reminds us that when it comes to women’s bodies, pockets of American society remain in the Dark Ages.

The latest trend is to make not only abortion illegal but even preventive measures of contraception.

There are people out there who would like to equate the use of contraception with abortion, and of course equate both of these with murder. This is not just the Catholic Church talking, either, but also various Christian denominations leading the call. The Rev. Dr. Matthew C. Harrison, president of the Lutheran Church — Missouri Synod, was quoted in the New York Times last week, telling a House committee on the subject: “We object to the use of drugs and procedures used to take the lives of unborn children,” referring not to abortion but to contraception. The idea that a bunch of Christian preachers are testifying in Congress about the future of women’s ability to use contraception is no less than frightening.

I may have inadvertently stepped into this with the article that my colleague, L Ariella Zeller, and I wrote about abortion in Israel in Lilith’s winter issue. We mistakenly conflated RU 486 and the abortion pill. Monica Whitcher, President of CHOICE: Campus Health Organization for Information, Contraception, and Education at Vassar College, corrected us in an email to Lilith’s editors, “RU486 is an abortion pill and terminates an established pregnancy. The morning after pill, by contrast, PREVENTS pregnancy, by either preventing the sperm from entering the egg, or by preventing a fertilized egg from implanting into the uterus.” I do apologize for the mistake and for unintentionally adding fuel to this fire.

- No Comments

February 17, 2012 by Guest Blogger

Spinoza and Cherry Ames

Like so many people who harbor secret sins and obsessions, I thought I was alone. And then one day, in the midst of a conversation, no doubt about high-level theological issues (or maybe where to go for lunch), with my friend and rabbinic colleague, Leah, I blurted it out: “did you ever read Cherry Ames when you were young?” She looked startled for a moment, and then responded, “I LOVED Cherry Ames!” Turns out, she and I are not the only ones who did (and do).

Like so many people who harbor secret sins and obsessions, I thought I was alone. And then one day, in the midst of a conversation, no doubt about high-level theological issues (or maybe where to go for lunch), with my friend and rabbinic colleague, Leah, I blurted it out: “did you ever read Cherry Ames when you were young?” She looked startled for a moment, and then responded, “I LOVED Cherry Ames!” Turns out, she and I are not the only ones who did (and do).

When I was a child, Cherry Ames was a favorite. Although I also read the Bobbsey Twins and Anne of Green Gables series, Cherry was the standout. Was it her black curly hair (like mine?) Was it her feisty independence? Was it her ability to solve every problem, not only of the medical variety, but mysteries of every kind? Was it her cute bedroom furniture in her home town of Hilton (Illinois)? Although I never expressed an interest in being a nurse, the Cherry Ames series (23 volumes in all), which portrayed a young woman who seemed to have a new doctor “suitor” in every book, yet always moved on to a new job leaving the would-be boyfriend behind, surely must have had some career-inspiring influence on me.

Somehow, unlike my Pee Wee Reese doll, several of my Cherry Ames books survived through adulthood. And I managed to find the remaining ones in second-hand bookstores and eventually on the Internet.

- 10 Comments

February 10, 2012 by Tara Bognar

State Funding and Fertility Treatments–In an Israeli Prison

http://www.flickr.com/wesbrowning

How seriously do we take reproductive rights and freedoms?

Israeli Prison Services (IPS) just agreed to fund fertility treatments for two convicted murderers who met and married while incarcerated. The two have the right to conjugal visits and their freedom to procreate is not restricted, but unlike other Israelis, they would not normally be entitled to state funding for fertility treatment. They were prepared to argue, in front of an administrative court, that that restriction violates their right to have children.

Equal access to reproductive freedom is a right long fought for by feminists. Still, reproductive freedom has meant different things to women in different social, economic, and cultural positions. In the United States, poor women, women of color, and women with physical and mental disabilities have fought against forced sterilization and even forced abortion, while other women must fight for access to voluntary contraception, sterilization, and abortions.

The idea that the state should actively decide who may have children touches on core issues of personal autonomy and bodily integrity. In the United States, even people who are convicted of abusing or murdering their children are not legally prevented from having other children.

If everyone else in Israel has the right to state funding for fertility treatments, can it be just, legal, or moral to deny that right to someone just because they are incarcerated? What if their life sentences mean that any children would inevitably become the wards either of the state or another family member? (According to current law, the child may be raised by their mother in prison until two years of age).

Because IPS voluntarily granted funding, no Israeli court had to make that decision.

- No Comments

February 7, 2012 by Guest Blogger

Peach Fuzz Lishma (for its own sake):(“Peaching, Not Preaching”)

Who picks peaches in August? Certainly not people like me, a rabbi who always anticipated the Jewish High Holidays by beginning to think about writing sermons as early as May. And by August – don’t ask!

Who picks peaches in August? Certainly not people like me, a rabbi who always anticipated the Jewish High Holidays by beginning to think about writing sermons as early as May. And by August – don’t ask!

But this year is different – now I’m semi-retired (and my husband retired 6 months earlier) and we are out on a weekday (!) in August picking peaches at Larriland Orchard in the countryside not far (but very far psychologically!) from D.C. Perfect sunny day, not humid, breathable air unlike much of the rest of the summer.

The two young women who are handing out the baskets for peach retrieval explain how to select the best peaches. No green on the flesh, a little hard (they’ll ripen in 3-5 days), these rows over here, not the ones farther back. For a born-and-bred city girl like myself, these directions are invaluable. And next to apples (for which I’ll return in a month), peaches are the easiest fruit to pick. The basket fills quickly, long before I’m tired or bored.

As we return to the vending stand to pay for our peaches, we find the two young women (interns? members of the family?) discussing the problem of their sensitivity to peach fuzz, how their constant exposure causes a kind of allergic reaction. Who knew?

Returning to the car, I begin contemplating this phenomenon, heretofore unbeknownst to me. Peach fuzz… the dark side of nature… environmental hazards?.. and suddenly, I realize what I’m doing. I’m thinking “sermon”; how can I possibly use this anecdote in a sermon?

- 7 Comments

February 1, 2012 by Tara Bognar

Modesty and Desire

http://www.flickr.com/center_for_jewish_history

Rabbi Dov Linzer, a prominent figure in Open Orthodoxy, recently published Lechery, Immodesty and the Talmud in the New York Times. The article explicitly responds to some recent attempts by ultra-Orthodox leaders in Israel to enforce their standards of “modesty,” (E.g.: Segregated elevators; segregated buses; a newspaper blurring out the mother’s face in the family picture accompanying the article about the murder of the mother and father). Linzer rebukes the ultra-Orthodox for hyper-sexualizing women and calling it “modesty” to police their dress and public presence. He cites Talmudic sources to correct the ultra-Orthodox understanding of Jewish law in this area. Linzer says:

The Talmud tells the religious man, in effect: If you have a problem, you deal with it. It is the male gaze — the way men look at women — that needs to be desexualized, not women in public. The power to make sure men don’t see women as objects of sexual gratification lies within men’s — and only men’s — control.

He concludes:

Jewish tradition teaches men and women alike that they should be modest in their dress. But modesty is not defined by, or even primarily about, how much of one’s body is covered. It is about comportment and behavior. It is about recognizing that one need not be the center of attention. It is about embodying the prophet Micah’s call for modesty: learning “to walk humbly with your God.”

- 7 Comments

January 26, 2012 by Guest Blogger

Beit Shemesh, Religious Extremism, and the Dignity of Women: Some Lessons from History

Vera Weizmann voting in Israel's first elections

The recent contretemps in Beit Shemesh riveted the Israeli public and brought worldwide attention to the misogynistic treatment accorded women in the public square by certain sectors of ultra-Orthodox Israeli society. As is by now well-known, some ultra-Orthodox Jews there hurled insults and engaged in bullying an eight-year-old Orthodox girl named Naama Margolese for dressing “immodestly” on her way to school. These same Jews also rioted when public street signs situated in an area inhabited by a population of ultra-Orthodox, Orthodox, and secular Jews that instructed women to dress according to their particular standards of modesty were removed. In recent months, ultra-Orthodox sensibilities have also led to the creation of bus routes where women are segregated and consigned to the back of the bus. On some public ceremonial occasions, women have been prohibited from singing lest their voices offend male listeners and on other occasions when women have sung there has been the spectacle of rabbis placing their hands over their ears to block out their sound. These episodes of Jewish religious extremism unconscionably objectify women and are absolutely incompatible with the democratic and egalitarian values upon which the State of Israel was founded.

This is not the first time such conflict between sectors of the ultra-Orthodox community and the other Jewish citizens of the State of Israel has been manifest. Indeed, such clashes predate the State itself. The ways in which secular and especially Orthodox religious leaders spoke out and acted in those cases provide models for how I would hope that present-day Israeli and Jewish religious leaders would respond to the concerns these events in Beth Shemesh and elsewhere evoke.

- 3 Comments

January 23, 2012 by Tara Bognar

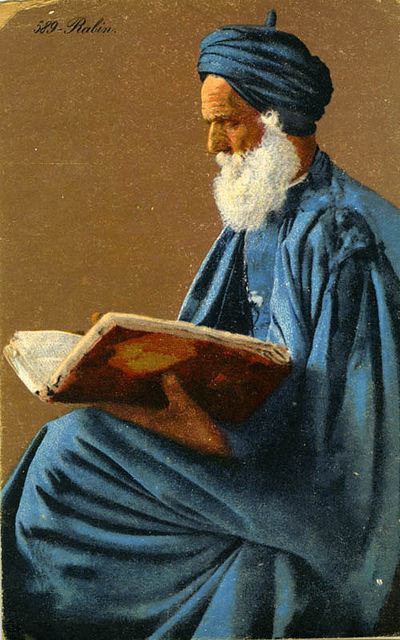

Muslim and Jewish Marriage Contracts in American Courts

As someone whose interest in secular law grew out of my studies of Jewish law, I’ve always been especially fascinated by the ways in which the two systems of law interact. A recently published article, “How To Judge Shari’a Contracts: A Guide To Islamic Marriage Agreements In American Courts,” got me thinking about some of the parallels and common experiences between Jews and Muslims in interacting with secular American courts.

As someone whose interest in secular law grew out of my studies of Jewish law, I’ve always been especially fascinated by the ways in which the two systems of law interact. A recently published article, “How To Judge Shari’a Contracts: A Guide To Islamic Marriage Agreements In American Courts,” got me thinking about some of the parallels and common experiences between Jews and Muslims in interacting with secular American courts.

Some Jewish Examples

Last month I was reading a case (Tsirlin V. Tsirlin, 2008) about an Israeli Jewish couple living in New York. The wife asked the husband for a get, the Jewish bill of divorce, and he gave her one in front of a Brooklyn Beit Din (Jewish court). The husband’s father brought the get to an Israeli court, on the strength of which the Israeli court issued a decree of divorce for the couple. Shortly afterward, the husband later filed for divorce in New York, also seeking orders for custody/visitation and child support. The wife moved to dismiss the action for divorce on the grounds that the New York courts should recognize the Israeli divorce. Judge Jeffrey Sunshine ruled that:

“If this court were to sanction the utilization of a ‘Get’ to circumvent the constitutional requirement that only the Supreme Court can grant a civil divorce, then a party who obtains a ‘Get’ in New York could register it in a foreign jurisdiction and potentially, later on, rely on the ‘Get’ to obtain a civil divorce in New York thereby rendering New York State’s Constitutional scheme as to a civil divorce ineffectual… It would have the practical affect [sic] of amending the Domestic Relations Law section 170 to provide a new grounds for divorce.”

- 1 Comment

January 20, 2012 by Guest Blogger

A Call for Civility for ALL Israeli Citizens

About a month ago I left Israel for a 10-day vacation, only to discover upon my return that it had become a different Israel. Gender segregation, an issue that NCJW has been involved in for years (e.g., Women of the Wall, the segregation on public buses, and the rights of agunot) had become front-page news with the story of Naama, a young child in Beit Shemesh taunted for her “immodest dress” by ultra-Orthodox zealots. Suddenly, it was the piece of news about which everyone — from Hillary Clinton to Prime Minister Netanyahu — was speaking.

About a month ago I left Israel for a 10-day vacation, only to discover upon my return that it had become a different Israel. Gender segregation, an issue that NCJW has been involved in for years (e.g., Women of the Wall, the segregation on public buses, and the rights of agunot) had become front-page news with the story of Naama, a young child in Beit Shemesh taunted for her “immodest dress” by ultra-Orthodox zealots. Suddenly, it was the piece of news about which everyone — from Hillary Clinton to Prime Minister Netanyahu — was speaking.

My own daughter, an officer in the Israel Defense Forces, was on her way home on leave when she was spat on and called names by an ultra-Orthodox zealot at a bus stop in Jerusalem. This is not a new phenomenon. What is new is that now, finally, the secular population is realizing that such incidents are not only about what “they” do in their own communities, but rather a symptom of the political system that has allowed religion to become part and parcel of civil government and civil society. The request of Haredi soldiers not to have to listen to women soldiers singing in an army choir is a perfect example of a system — put into place with good intentions — that has gone wrong. What if secular soldiers refused to listen to the Kiddush (blessing over the wine) at Friday night Shabbat meals? Or, if Druze soldiers demanded bread to be served alongside matzah on Pesach? Would that be respected as well?

I remembered when many years ago, the Ponovitch Rav, the great spiritual and intellectual leader of Lithuanian Judaism (the non-Hasidic branch of Haredi Judaism) came from Israel to Miami, where I grew up. My father went with my mother, both without head coverings, to pick him up at the airport. My mother, out of respect for the Rav, who was then old and frail, immediately took a seat in the back of the car, in order to allow the Rav to sit up front with my father. “Absolutely not,” declared the Rav, “I would never separate a husband and wife.” And so the great Rav sat in the back of the car with my mother in front alongside my father.

- 3 Comments

January 12, 2012 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

A Conversation With Jane Lazarre

In the summer of 2009, Lilith excerpted a section of Jane Lazarre’s harrowing novel, Inheritance. The book was recently published and Lilith’s Fiction Editor, Yona Zeldis McDonough, interviewed Lazarre–author of ten books and creator of the undergraduate writing program at Eugene Lang College at the New School—about historical fiction, blacks and Jews, and her feelings about our first mixed-race president.

In the summer of 2009, Lilith excerpted a section of Jane Lazarre’s harrowing novel, Inheritance. The book was recently published and Lilith’s Fiction Editor, Yona Zeldis McDonough, interviewed Lazarre–author of ten books and creator of the undergraduate writing program at Eugene Lang College at the New School—about historical fiction, blacks and Jews, and her feelings about our first mixed-race president.

Your work is full of interracial relationships; what drew you to this subject?

The first reason is that in my early twenties, I married into an African American family, and in 1969, I gave birth to my first son, a few years later to my second son. Raising Black children, and learning about this nation’s history from the point of view of Black people in my family – a very different perspective than the one I was raised with, that most white people were/are raised with – was a transformational experience.

The theme of race, though secondary, is a central one in my first memoir, The Mother Knot, written in the midst of the feminist movement in the 70s, a movement that was beginning to produce a wealth of material and testimonials, both scholarly and literary, about race history, and by both African American and white writers. Soon after that, as a professor of writing and literature, first at City College in New York, then on the full-time faculty of Eugene Lang College at the New School, I had the opportunity to study and teach African American literature, with special attention to the rich tradition in autobiography. These years of study and teaching had a huge impact on me, on my sense of my own identity as an American, as a white Jewish mother of Black sons, I told some of this story autobiographically in a memoir called Beyond the Whiteness of Whiteness. But apart from the personal sources of my work, I am committed, as a writer and activist-teacher, to speak out against some of the mythologies, indeed, the lies and self-deceptions, of American race history and American racism. The theme of mixed racial identities, about which there is plenty of personal and philosophical disagreement, is also one that has been distorted and misrepresented in many ways since the early days of slavery and up to the present moment – in some of the ways, for example, in which we discuss, define and interpret the history and policies of President Obama.

- 3 Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...