The Lilith Blog

December 3, 2013 by Maya Bernstein

Thanks-giving

Last year, this time, I was struck with an unexpected virus, which sent me spinning. It hit me out of the blue, while I was swimming. The pool seemed to be in strange constant motion even when I was gripping the wall, as if the waters were rocking me, sending me back and forth, back and forth. It reminded me of the small pool in the motel in Santa Monica, where my family would stay when visiting my father’s parents, who had moved to L.A for the weather from the grimy, snowy Bronx. We were there in 1989, when the massive earthquake hit San Francisco, and the pool in that motel looked like someone had lifted it on one side and dropped it down, hard. Water sliding wave-like, up and down, back and forth, for hours and hours.

Last year, this time, I was struck with an unexpected virus, which sent me spinning. It hit me out of the blue, while I was swimming. The pool seemed to be in strange constant motion even when I was gripping the wall, as if the waters were rocking me, sending me back and forth, back and forth. It reminded me of the small pool in the motel in Santa Monica, where my family would stay when visiting my father’s parents, who had moved to L.A for the weather from the grimy, snowy Bronx. We were there in 1989, when the massive earthquake hit San Francisco, and the pool in that motel looked like someone had lifted it on one side and dropped it down, hard. Water sliding wave-like, up and down, back and forth, for hours and hours.

Now, with the gift of distance, the appreciation that it was not so bad, a case of vestibular neuritis, a relatively common infection of the inner ear, which causes extreme vertigo and can take up to 6 months to heal, I feel rather like the protagonist in Lionel Shriver’s recent story in the New Yorker, who, after a frightening experience in an African creek, “was disheartened to discover that maturity could involve getting smaller. She had been reduced. She was a weaker, more fragile girl…” This is contrary to that sentiment that what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. I have been feeling that perhaps becoming stronger involves admitting where one is weak. It is strange, uncertain territory for me.

When I was healing, my family spent a long-weekend away together. I was well enough to make the car journey, and to take slow walks, breathing in the cold fresh air, and to make pasta and hot cocoa. For those few days, we had no agenda other than to be together, move from inside in our PJs to outside in our boots, and back inside again. The kids watched clips of the Sound of Music over and over, and then acted out the songs in the elaborately planned productions that young children put on when they’re not being rushed off to school or sports or lessons. My illness had forced me into a strange alternative, parallel universe, moving at a radically different speed. I was on sick leave from work, couldn’t drive, couldn’t sit in front of the computer, and spent many days lying on the couch, looking out the window. That weekend, my family cautiously and kindly entered my forced, unnatural time zone, and it was unexpectedly delightful. We all lay on the couch together, watching the misty morning light turn to the bright blue of day, then wane into the lavender evening, and when our own reflections stared back at us from the glass, we turned to each other and smiled.

This year, we are heading back to the same area to celebrate Thanksgiving. Already, it is a very different trip. We are back in the time zone of the healthy. We are signing the kids up for ski lessons. We are bickering over what to bring. In these days before we go, I am preparing for a big business trip, trying to meet deadlines, checking emails at red lights, attending my children’s Thanksgiving shows, and packing up the family. The memory of sitting still and looking out the window feels as if it is somehow not my own. As if it is part of some other lifetime, some other being.

- 2 Comments

December 2, 2013 by Elizabeth Mandel

Goldieblox and the Three Girls

For Hanukkah, my daughters (ages 6.5, 4.5 and 1.5) are getting a range of gifts that are great for girls. These include K’Nex (my older girls just built an amazing roller coaster and are looking to expand their amusement park), a remote controlled robot kit (my eldest year old attended vacation robot camp over Veteran’s Day and filed the experience on her Things That Are The Best Ever list), Magnatiles and SnapCircuits.

For Hanukkah, my daughters (ages 6.5, 4.5 and 1.5) are getting a range of gifts that are great for girls. These include K’Nex (my older girls just built an amazing roller coaster and are looking to expand their amusement park), a remote controlled robot kit (my eldest year old attended vacation robot camp over Veteran’s Day and filed the experience on her Things That Are The Best Ever list), Magnatiles and SnapCircuits.

Yes, these gifts are great for girls. These gifts are great for kids, and surely girls fit into that category. These toys help children learn to follow directions, teach them spatial relations and encourage fine motor skills, give them opportunities for storytelling and cooperation, engage their imaginations and their innate interests in building, and give them a well-earned a sense of pride and accomplishment. They’re also really fun, which I believe is the best kind of learning.

This gift list does not include GoldieBlox, the much-hyped “engineering for girls” toy that hit the web with a sonic boom on Kickstarter last year, and has upped its own ante with commercial that has gone viral. If you haven’t seen it (you can watch it here), it features three girls who overturn media assumptions about what girls like by building an extremely sophisticated Rube Goldberg machine using, among other things, a pink tea set.

- 2 Comments

December 2, 2013 by Danica Davidson

Women’s Voices Through Comics

Sarah Lightman is an artist, curator and academic with a special interest in Jewish women creating autobiographical comics. She’s the co-curator of the touring museum exhibit Graphic Details: Confessional Comics and has just completed editing the book Graphic Details: Essays on Confessional Comics by Jewish Women, which will be published next year by McFarland. This will be followed in 2015 by her own autobiographical graphic novel, The Book of Sarah to be published by Myriad Editions in 2015. Lightman is also a director of Laydeez Do Comics, the first women’s led comics forum to focus on autobiographical comics with branches in the UK, Ireland and USA. While the concentration is on women, anyone may attend.

Sarah Lightman is an artist, curator and academic with a special interest in Jewish women creating autobiographical comics. She’s the co-curator of the touring museum exhibit Graphic Details: Confessional Comics and has just completed editing the book Graphic Details: Essays on Confessional Comics by Jewish Women, which will be published next year by McFarland. This will be followed in 2015 by her own autobiographical graphic novel, The Book of Sarah to be published by Myriad Editions in 2015. Lightman is also a director of Laydeez Do Comics, the first women’s led comics forum to focus on autobiographical comics with branches in the UK, Ireland and USA. While the concentration is on women, anyone may attend.

Danica Davidson, whose journalism on graphic novels has been published by Lilith, MTV and CNN, interviewed Lightman.

Danica Davidson: Can you tell us about Graphic Details: Confessional Comics by Jewish Women?

Sarah Lightman: Graphic Details is co-curated by myself and Michael Kaminer, who’s a New York-based journalist and comics collector. He wrote an article for the Jewish Daily Forward about some Jewish women comic artists he’d seen at a comics event. I read the article and realized that was exactly what I was doing in the UK, but I hadn’t found many other Jewish people doing the same thing. It was really exciting. I suggested to Michael that we make an exhibition out of his article, because I had already curated a number of shows, including a series on contemporary artists at Ben Uri Gallery, the London Jewish Museum of Art in London. Also, I’d just curated a show “Diary Drawing,” at The Centre for Recent Drawing, with Ariel Schrag and Miriam Katin. So I already knew a few Jewish comic artists but I didn’t realize there were quite so many making autobiographical comics!

The project snowballed from there, and it’s been touring for three, four years. It’s opening in Miami at the end of the month, at the Jewish Museum in Florida. The show is coming to London at the end of next year to a really great gallery called Space Station Sixty-Five. We’re going to be doing a one-day symposium about Jewish women comic artists at JW3, the new Jewish Community Centre for London, and we’re looking to do a study day as well for artists.

I just finished editing the book about the exhibition, and it’s about 400 pages. It will be published by McFarland, and it’s got essays and interviews, information and images about all the artists in the show. It’s going to be the first book ever published to focus on Jewish women in comics.

DD: What other work have you done to promote the work of women in the comics field, particularly Jewish women?

SL: When the exhibition opened in New York, I co-chaired a symposium with two New York academics, Tahneer Oksman and Amy Feinstein. I’ve just written a chapter about Diane Noomin’s comic, called “Baby Talk: A Tale of Four Miscarriages” that’s in Trauma Narratives and Herstory published by Palgrave Macmillan. None of the other essays in the collection were about graphic novels and it’s always great to bring comics to a new audience. I’ve written for websites, books and newspapers about Jewish women and comics. For example, I contributed to 1001 Comics You Must Read Before You Die, so I wrote about Charlotte Salomon, Ariel Schrag, Gabrielle Bell. I can make sure these women get included in collections. I also wrote about Jewish Women and Comics for the new Routledge Handbook to Contemporary Jewish Cultures(2014). Most recently I wrote for the Canadian website “A Bit off the Top” on the Israeli comic artist Ilana Zeffren.

I’m also doing a doctorate on autobiographical comics at University of Glasgow: “The Drawn Wound: Hurting and Healing in Autobiographical Comics.” I’m really interested in traumatic narratives and how people draw and visualize their lives and whether there’s potential for something called Post Traumatic Growth. It’s the idea that if something terrible happens, your life can change for the better. I’m especially interested in exploring how the creative process of making comics can make a difference.

In addition, I’m looking at how Jewish women have been written out of Jewish textual history and intellectual history, and how they’re using comics now to ensure their voices and life experiences are heard and recorded.

- No Comments

November 26, 2013 by Chana Widawski

A Lady and Her Bicycle

I couldn’t believe it — I had jumped into the pages of National Geographic. I had sprung myself across a rickety makeshift bridge, gaping at a raging river in the highlands of West Papua, Indonesia, and there I stood, mesmerized by a procession of men wearing nothing but feathers in their hair and koteka, gourds, on their penises.

I couldn’t believe it — I had jumped into the pages of National Geographic. I had sprung myself across a rickety makeshift bridge, gaping at a raging river in the highlands of West Papua, Indonesia, and there I stood, mesmerized by a procession of men wearing nothing but feathers in their hair and koteka, gourds, on their penises.

I stood in the misty rain, alongside my Papuan guide whose teeth were red as blood from chewing betel nut, praying that I wouldn’t catch fleas from sleeping in the round straw hut where I would be bunking with the village’s women, children and pigs. That night I sat around the hut’s lung-choking smoky fire exchanging shy stares and smiles with the Dani women and children, as we each grabbed fingers full of cooked sweet potato greens, slurping them noisily into our mouths. Rather than stressing about the rat scurrying around the edges of the hut’s rounded walls, I focused on the young girl making a bilum, a string bag for carrying anything from babies, to newborn pigs, to hundreds of pounds of sweet potatoes.

I couldn’t believe I was there. Me, a young Jewish woman from Rochester, New York. I had somehow managed to become a person who cycled the crowded streets of Cambodia, biked the mountains of northern Thailand and was now in a remote village worthy of National Geographic. It was intoxicating.

So you can imagine my excitement when, back in my New York humdrum life, I stumbled upon a book about Annie Londonderry, the first woman to cycle around the globe. And no, she didn’t do it in the 1990s. It was the 1890s! Obsessed with everything bicycle and energized by travel stories, particularly those of intrepid women, I couldn’t wait to get my hands on a copy of her biography Around the World on Two Wheels: Annie Londonderry’s Ride. When I learned that Annie Londonderry’s real name was Annie Cohen Kopchowsky, that her first language was Yiddish, and that she lived with her peddler husband, kids and extended family in a crowded tenement in Boston’s West End, I was entranced.

When Annie set out on this epic journey as a novice biker at age 24 in 1894, it was because two wealthy men were betting whether a woman could fend for herself and earn $5,000 while cycling the world in 15 months. Much was happening in both the women’s movement and the bicycle craze, and Annie was zealous about cycling her way out of the traditional woman’s role. She happily reinvented herself with an exciting new identity, found lots of sponsors, and gained both freedom and fame.

- No Comments

November 25, 2013 by Patricia Grossman

The Courage and Criticism of a War Correspondent

There is a remarkable visual clarity in Michele Zackheim’s “Last Train to Paris,” set predominantly in Paris and Berlin during the rise and fall of the Third Reich. Perhaps reflecting Zackheim’s background as a visual artist, the novel is as adept at crystallizing small moments as it is at portraying the sweep of action during the darkest time in 20th century Europe. The story is told by Rose (R.B.) Manon, an old woman looking back at her career as a political reporter and war correspondent for The Paris Courier.

There is a remarkable visual clarity in Michele Zackheim’s “Last Train to Paris,” set predominantly in Paris and Berlin during the rise and fall of the Third Reich. Perhaps reflecting Zackheim’s background as a visual artist, the novel is as adept at crystallizing small moments as it is at portraying the sweep of action during the darkest time in 20th century Europe. The story is told by Rose (R.B.) Manon, an old woman looking back at her career as a political reporter and war correspondent for The Paris Courier.

“With soaring lyricism, Zackheim limns an exquisitely haunting portrait of an indelibly scarred, yet deeply passionate, woman.” – Booklist

Rose’s cousin is kidnapped and then killed in Paris. In real life, the kidnapper was Eugene Weidmann, and the abductee was a distant cousin of yours. Was this a story you were familiar with as a child?

No, I learned about this story by accident when I was an adult. I was fascinated by Janet Flanner and had checked out her book Paris Was Yesterday, 1925 –1939. In it was an essay she wrote for The New Yorker that spoke about the murder.

The appearance of Colette and Janet Flanner in this novel is both natural and fun to read. Were their parts fun to write?

I loved making friends with Colette and Janet Flanner. Their involvement in my distant cousin’s murder makes them more life-like, less mysterious. When Flanner calls my cousin, “a grabby little American,” I’m upset. How dare she call my cousin, ‘grabby”! My response brings me a step closer to Flanner as a real human being, rather than an icon.

- No Comments

November 22, 2013 by Anna Schnur-Fishman

8 Lessons for Hanukkah, Useful All Year

A Hanukkah treasure from the Lilith archives!

Ten hanukkahs ago, when I was about four and my brother nine, my parents decided that it was time to make giving tzedakah a family project, and not just something they did on their own. They coupled this idea with another—their wish to take some of the consumerist curse off December—and instituted the following ritual. Here is the ceremony as we do it, including eight Hanukkah lessons I’ve learned from it.

Around October, my parents and brother and I begin throwing all of the tzedakah appeals that arrive in the mail into one big basket. By December it’s stuffed.

Hanukkah Lesson #1: It is amazing how many organizations need money.

A week or so before Hanukkah begins, we all sit down and sort through the envelopes, tossing out the ones that none of us really cares about. For each one that is left (maybe 20 or 25)— and any other tzedakahs we like thrown in, too—we make an index card. (As a compulsive family, we excel at activities that involve lining up cards in little rows on a table. I tend to get carried away arranging the cards alphabetically, categorically, and by the date of the appeal, but this really isn’t a necessary part of the process.)

Next, one person describes whatever organizations the others don’t know much about. This year, for example, my brother has been very involved with an orphanage in Delhi, India, so he spoke quite eloquently on behalf of his index card, waving it in the air and pressing it to his chest. Hanukkah Lesson #2: Speak out for what you believe in. We do this because we soon vote on the tzedakahs we want to give to, and because “it’s important,” as my father says every year, “to be educated voters, and to make educated decisions.” This is Hanukkah Lesson #3.

- No Comments

November 21, 2013 by Chanel Dubofsky

My “Good Woman” Brain

I grew up on tea. Lipton, with lots of milk and sugar. I didn’t know about the herbal kind until college, which, it turns out, I don’t actually like; everything but that sugary, almond colored tea tastes like hot, wet grass.

I grew up on tea. Lipton, with lots of milk and sugar. I didn’t know about the herbal kind until college, which, it turns out, I don’t actually like; everything but that sugary, almond colored tea tastes like hot, wet grass.

Yesterday I drank a lot of green tea. I spent the previous 24 hours sicker than I’ve been in a very long time. (The kind of sick you don’t want me to describe in a blog post.) The kind of sick that made me terrified of anything but dry toast, ginger ale and tea that I don’t even like.

Today was my foray back into dairy. It was fine, mostly, except for the part of my brain that was triggered by the fact that for the last few months, I’ve avoided dairy. Not because of my stomach (I am not among the lactose intolerant Jews), but because I’ve been kind of vegan-y lately.

I have a lot of qualms about veganism. There’s the class privilege piece–protein substitutes and the loads of fresh vegetables are expensive and not accessible to everyone. There’s the judgment and fat shaming piece that tends to rear its head–if only you could control yourself, if you only had your priorities straight and right, if you could only be less selfish and less wasteful.

I kept kosher for ten years. I stopped for a few reasons–I couldn’t find meaning in it anymore, I was no longer invested in halacha (it’s doubtful that I ever was, no matter how much I tried to convince myself that I wanted to be), but mainly, I was using kashrut as another way to control food, and not in a holy way. I wanted to be a person, a woman, who controlled food. A good woman.

A good woman shows everyone that she is trying, one way or another, to be better. She talks about going to the gym, how much she goes, how long she spends there. When her coworkers bring in baked goods or other treats, she will ignore them, or she will eat one and then say, “Oh, this is so bad for me!” She will say to others who do not eat it, “You have so much self control!” A good woman feels badly about her weight, no matter what it is. As long as she knows that she is not okay the way she is, she is good.

It’s this “good woman” brain, sexist and awful as it is, that comes back when I do things like tell myself I’m going to stop eating dairy. I recognize it. It’s the same thing I used to do when I kept kosher–I would never, ever eat a cheeseburger again. Look how strong I am. I am a person who does not need a cheeseburger. Even better, I don’t want a cheeseburger. I am a good woman. I have strength.

I ate a cheeseburger. I ate dairy. I’ll eat them again. I’ll eat them because I know what the bottom of that hole of “ not eating that ever again” looks and feels like. Doing that makes me hate myself, which is exactly what the sexist machine wants- to distract us from being powerful by making us believe we are never good enough. I ate it because I don’t need to be a good woman or a good Jew, I need to be a real person.

photo credit: michael+yan via photopin cc

- No Comments

November 20, 2013 by Amanda Walgrove

The Shondes: Anthems for Your Inner Outsider

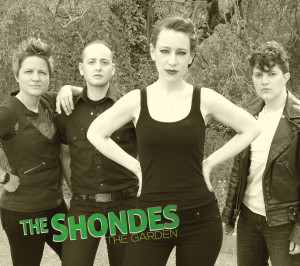

Since they started making waves with their 2008 debut album, “The Red Sea,” Brooklyn’s homegrown rock band, The Shondes, have lived up to their Yiddish-inspired name. Providing anthems for everyone’s inner outsider, they’ve been shaking up the music scene with influences from Riot Grrrl, traditional klezmer music, and feminist punk rock, all wrapped into one package.

Since they started making waves with their 2008 debut album, “The Red Sea,” Brooklyn’s homegrown rock band, The Shondes, have lived up to their Yiddish-inspired name. Providing anthems for everyone’s inner outsider, they’ve been shaking up the music scene with influences from Riot Grrrl, traditional klezmer music, and feminist punk rock, all wrapped into one package.

Back in 2011, I interviewed the band before the release of their third album, “Searchlights.” Now, as they spiral down from the nationwide tour of their fourth full-length album, “The Garden,” I caught up with The Shondes’ front-woman, Louisa Solomon, to learn more about writing songs for radical organizing and what it means to never give up on The Garden.

AW: Was there a Biblical influence for the song and album title, “The Garden”?

LS: In the sense that the garden of Eden is an unavoidable cultural frame for thinking about growing up, loss, disillusionment, and all of that. It’s common ground in a way for getting into all the interesting stuff inside it. But really we were thinking of a non-specific imagined garden, as a kind of holding place for parts of yourself, precious things you’ve given up but know are still out there in some form, somewhere. It begs all the questions that go along with pain and loss and growth: where does stuff go when we cast it off, and what’s it like if we try to retrieve it? It’s just an interesting landscape to spend some time in.

AW: Who are you most inspired by, musically or otherwise?

LS: I am really inspired by people who find ways to make stuff happen, against the odds, against the flow.

I am definitely inspired by my sister Claire, who, in addition to being a creative and brilliant academic and educator, is a completely genius fiction writer. Her novels read like nothing else. She is so adept at playing with form that the story never suffers for its own subversions and explorations. I think about that a lot when writing songs — how to keep experimentation in service of the song.

My musical inspirations are varied, but united by their ability to make me feel big feelings: soul, punk, some pop (though I’m picky), and anthemic rock. That’s most of what I listen to these days. I’m a sucker for a well-written song.

I’m inspired by musicians/friends in Brooklyn who are working hard like we are to write solid songs and share them with people, while making rent in an amazing city. Leda, Chris McFarland, and Laura Stevenson are all good examples.

And of course my love, New York itself, is an ever-present source of inspiration.

- No Comments

November 19, 2013 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

She’s a Writer. She’s Very Nosy.

In Lisa Gornick’s haunting second novel, Tinderbox, a young nanny recently arrived from Peru rattles both the composure and professional ethics of psychoanalyst Myra Gold. But this is not new territory for Gornick, who is on the faculty at the Columbia University Center for Psychoanalytic Training and Research and a graduate of the writing program at New York University. Her first novel, A Private Sorcery, revolved around Saul Dubinsky, a sensitive, dedicated psychiatrist who turns to drugs after the suicide of a patient. Gornick recently chatted with fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the ways in which the fields of literature and psychotherapy feed each other, the Jewish experience filtered through the lenses of Morocco and Peru, and the redemptive power of fire.

In Lisa Gornick’s haunting second novel, Tinderbox, a young nanny recently arrived from Peru rattles both the composure and professional ethics of psychoanalyst Myra Gold. But this is not new territory for Gornick, who is on the faculty at the Columbia University Center for Psychoanalytic Training and Research and a graduate of the writing program at New York University. Her first novel, A Private Sorcery, revolved around Saul Dubinsky, a sensitive, dedicated psychiatrist who turns to drugs after the suicide of a patient. Gornick recently chatted with fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the ways in which the fields of literature and psychotherapy feed each other, the Jewish experience filtered through the lenses of Morocco and Peru, and the redemptive power of fire.

YZM: You are a novelist with training and degrees in clinical psychology and psychoanalysis; can you talk about how fiction writing and psychology come together (if they do) in your work?

LG: Last summer, I stayed at a bed and breakfast in Maine. Next to the main house was an enormous old barn that stretched towards the back of the property like a railroad car. It was sealed tight as a drum, but my antennae went up: inside that barn was a story. My husband watched me reading the literature about the property (the house had once been the home of the Woolworth brothers who’d raised prize harness race horses and entertained the likes of Clark Gable), examining the photographs in the album left out in the breakfast room, striking up a conversation with the current owner, and, of course, ultimately asking if he would open the barn doors for me. “She’s a writer,” he apologized to the owner. “She’s very nosy.”

Although handled with more tact and in the service of healing, nosy equally describes the psychoanalyst, also always on the alert for the moments when emotions peek out from the crevice between words and their cadence, for the pulse points in a patient’s stream of words, for the places where a gentle inquiry, perhaps just the repetition of the patient’s words, will open a door. In an essay “Analyzing and Novelizing,” I gave the much altered example of a remote scientist who, after many months of treatment, used the phrase, “When we lived in Old Millbrook,” and how it was my writerly ear that sensed the tragic story behind these seven syllables.

Freud, whose early immersion in literature and writing suggests he might with a different turn of events have become a novelist himself, was deeply ambivalent about creative writers, a subject I’ve written about in an essay “Freud and the Creative Writer.” On the one hand, he credited creative writers with having already discovered everything analysts would learn in their consultation rooms. On the other hand, he viewed creative writers as on the verge of psychosis. Putting aside these idealizing and devaluing extremes, analysts and creative writers clearly share many tools — free association, attentiveness to language, dreams. Most centrally, both work with narratives, how they are constructed and unfold, an initial tale often hiding a more complicated and taboo story yet to be told.

- No Comments

November 15, 2013 by Amy Stone

Losing My Virginity: Of Romance and Property Rights

The filmmaker in a virginal white wedding gown.

If only Therese Shechter’s film “How to Lose Your Virginity” had been around when I was a college student obsessing about “saving it.” Freed from endless years of mental anguish, I probably would have had enough time to graduate Phi Beta Kappa and, who knows, maybe even have some good sex.

Or not. …

The film gets its US premiere this Sunday, Nov. 17, at 9:30 p.m. at the DOC NYC film festival at the SVA Theater, 333 West 23rd Street. The screening will be followed by a Q&A with director Therese Shechter and producer Lisa Esselstein.

Sixty-plus minutes of virginity, virginity, virginity makes you feel like you’ve been exorcised from ever again wanting to think about the V-word. Shechter, a nice Jewish art student from the Toronto suburbs, now a filmmaker in Brooklyn, has truly delivered a film that entertains, horrifies and instructs.

Get ready for details of America’s chastity balls (next step chastity belts?), where girls hand over their virginity to their fathers for safekeeping until dads deliver the precious commodity to the future husbands. Get ready for the TV vampire whose hymen keeps growing back again and again, forcing her to go through first-time intercourse pain for eternity. And get ready for some healthy advice from former Surgeon General Joycelyn Elders. One memorable piece of government information: 50 million in tax payers’ dollars goes to fund abstinence programs in the schools that are both unscientific and ineffective. (Is it too much to hope that this will get axed in government cutbacks?) And get ready for a wildly inclusive array of women, including the filmmaker, weighing in on virginity.

- 1 Comment

Please wait...

Please wait...