November 15, 2011 by Naomi Danis

Feminists in Focus: Dolphin Boy

I am an Israeli film junkie. Even though I visit my beloved other country often, I also depend on and delight in getting extra fixes of Israel vicariously through its films.

I am an Israeli film junkie. Even though I visit my beloved other country often, I also depend on and delight in getting extra fixes of Israel vicariously through its films.

When Meir Fenigstein’s Israel film festival comes to New York, for 25 years already, I am there. Each year, no matter how late the schedule is published, the theater always fills up. My theory is that we are a traumatized people, Israelis, and Jews, and that any time someone is retelling our story with imagination and courage, giving us a new narrative of familiar and often painful experiences, we want to hear and see what they have to say. We show up.

On Thursday night I wouldn’t have missed the opening of the 5th annual Other Israel Film Festival. This festival of films by and about Israel’s minority communities and especially the Arab citizens of Israel, is always provocative, sobering, bittersweetly entertaining–and if sometimes disheartening in its exposure of deeply felt injustices–always hope-inspiring because of the very fact of the festival’s existence.

The opening film this year, “Dolphin Boy,” a feature length documentary, is narrated in English (with subtitles for the Hebrew and Arabic) by an Israeli Jewish psychiatrist telling the story of his patient, a 17-year-old Palestinian Israeli young man, who is brought to him after a traumatic beating at the hands of other young men from his village avenging what they misconstrued as an “honor” violation. The film covers a period of four years of healing, and is a story about vulnerability and love, about relationships, between doctor and patient, father and son, boy and dolphins. This documentary like the arenas it portrays, medical treatment and nature, transcends politics.

- 1 Comment

November 15, 2011 by Nancy K. Kaufman

Riding the Buses in Jerusalem

Cross-posted with The NCJW Insider.

Photo Courtesy of NCJW

I am writing from Jerusalem where I am on a study tour with 23 women from the National Council of Jewish Women. We are here visiting some of the organizations we fund through our Israel Granting Program and also are meeting with a variety of people to get updates on the social, political, and economic issues facing the modern State of Israel. One issue I never quite thought I would experience in 2011 is bus segregation. No, I am not referring to blacks and whites because, after all, this is not 1960 in Mississippi. I am referring to gender segregation of men and women on buses with routes originating from the predominately Orthodox neighborhood of Ramat Shlomo in Jerusalem. Today, we rode the buses to experience firsthand what it is like to be a woman and assume you must “go to the back of the bus” when you board bus #56 or #40.

This now illegal activity started in 1997 when public transport companies began to operate special bus lines for the Haredi public, starting with two lines in Jerusalem and Bnei Barak. Called “Mehadrin” (extra kosher) lines, women would board the bus through the rear door and men would board through the front door. Women who objected to these rules would be subjected to harassment and intimidation and, in some cases, physical violence. The Israel Reform Action Center (IRAC) began to take action on this subject in 2001 and NCJW followed soon after. During a hearing on the case in January 2008, the Israeli Supreme Court criticized the manner in which gender segregation was being carried out on the buses and instructed the Ministry of Transportation to appoint a committee to study the matter. The Committee submitted its conclusions in October 2009 and found that bus routes applying gender segregation were unlawful given existing laws of the State of Israel; however, “segregation” was not defined and no enforcement mechanisms were put in place. The court has since ruled that signs must be placed in buses stating: “Due to Supreme Court ruling 47607 people can sit anywhere they want on the bus.”

- 1 Comment

November 10, 2011 by Jill Finkelstein

Link Roundup: A Spotlight on Gender Segregation

http://www.flickr.com/theeerin

Over the past six months, the news has been filled with stories about gender segregation and gender discrimination in Israel and the Jewish community. From the Hillary Clinton Photoshop fiasco to the recent Brooklyn bus scandal, here’s a look at the biggest headlines.

In May, the Brooklyn-based Orthodox weekly Di Tzaytung digitally removed Hillary Clinton and Audrey Tomason from the famous Situation Room photograph following the death of Bin Laden. Since then, new stories have been reported about the absence of women from Jerusalem billboards and ads as well as the exclusion of girls from Clalit HMO stickers, which are given to children as prizes at doctors’ offices. Images of women were also removed from the National Transplant Center (ADI)’s bus ads for its organ donation campaign in Jerusalem and Bnei Brak. Last week, the pluralistic organization Yerushalmim began fighting back by inviting women to be photographed for its “Uncensored” poster campaign. The organization plans to hang the posters around the city in order to return Jerusalem to its “natural state.” [Haaretz]

In June, we reported that the Ultra-Orthodox community in posted flyers around Old City Jerusalem insisting women either stay home or take an alternate, longer, route to the Kotel on Shavuot. Despite the controversy caused by the signs and a court ordered ban on segregation, the Haredi community of Mea She’arim imposed its own segregation policy during Sukkot. Efforts to fight the segregation were unsuccessful as Jerusalem City Council Member Rachel Azaria was fired for petitioning the High Court to uphold the ban. Listen to her interview with Rusty Mike Radio. [The Sisterhood]

- 1 Comment

November 10, 2011 by Amanda Walgrove

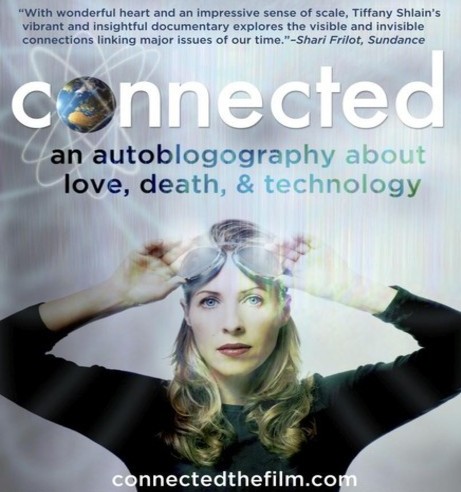

The Quest for Connection

Tiffany Shlain’s newest film, “Connected: An Autoblogography About Love, Death & Technology,” explores the history of human interaction, and the hope that natural and technological connections don’t have to be mutually exclusive.

Tiffany Shlain’s newest film, “Connected: An Autoblogography About Love, Death & Technology,” explores the history of human interaction, and the hope that natural and technological connections don’t have to be mutually exclusive.

Honored by Newsweek as one of the “Women Shaping the 21st Century,” Tiffany Shlain has been making films for nearly two decades. Somewhere in the middle, when she was 26, she also founded the Webby Awards.

It wasn’t until “Connected” that the filmmaker made the decision to step in front of the camera herself. Says Shlain, “I chose to speak my truth in order to speak to some universal truth. That was my guiding principle.” When she suddenly received news that her father had nine months to live and that she was pregnant with a second child, Shlain decided that telling her own story would ultimately convey the true struggle of what it means to be connected. The film encourages a return to our roots, to the fundamental values of human interaction and the use of social networks as support systems.

- No Comments

November 8, 2011 by Tara Bognar

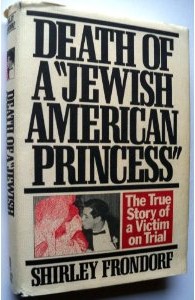

Enough with stereotypes

The media coverage and commentary immediately following Sam Friedlander’s murder of his wife Amy and their two children included a disturbing level of victim-blaming:

The media coverage and commentary immediately following Sam Friedlander’s murder of his wife Amy and their two children included a disturbing level of victim-blaming:

Michael Borg: “I have heard from him the abuse she put him through in terms of belittling and emasculating him in front of the kids and in front of friends.”

David Pine: “He looked like an emotionally beaten man… I can’t put a handle on why he would take the lives of his kids, but whatever it was was a result of years of emotional torment that he must have (gone) through in that household.”

A childhood acquaintance asked on his blog: “Did his wife’s remarks bring him back to a time when he really was a small person?

The problem of victim-blaming is sadly widespread, and three different local groups, Hope’s Door, My Sister’s Place and the Westchester Hispanic Coalition staged a rally to raise awareness of the issue.

But I think that the language used here points to a specifically Jewish problem. It strongly evokes certain stereotypes about Jewish women and men: the domineering, emasculating Jewish woman, and the meek, dominated Jewish man. Whoever Sam and Amy really were and however their relationship played out, these stock characters help mask the absurdity of the implication that Amy Friedlander was or even could have been morally responsible for her husband’s murderous actions.

- No Comments

November 8, 2011 by Amy Stone

Occupy Judaism – More Than A Damn Good Slogan?

Photo by Amy Stone

Is Occupy Judaism no more than a great slogan, springing from the head of social media maven Daniel J. Sieradski? Or is it verbal fuel with the power to ignite a democratic free-for-all within Judaism akin to the Occupy Wall Street movement it supports?

With the end of the High Holiday activities connected to OWS across the country, what next – if anything?

So far no catchy chants or songs for Occupy Judaism (correct me if they’ve sprouted forth.) The lyrics streaming on mp3 Wall Street Main Street from Chana Rothman, deeply involved in both Occupy Philly and Occupy Judaism, are strictly secular: “Wall Street Main Street what’s it gonna be? How we gonna handle this inequality?” Born in Toronto, she sees Occupy Judaism as “so Jewish and so American. It’s kind of like Heschel marching with Martin Luther King, praying with his feet. … obligated as a Jew, as a Jewish leader to do the right things in the world.” But how does that play out?

Philadelphia visual artist Zoe Cohen says, “Just by holding these events we’re trying to push Jewish organizations to consider being part of this movement.” And if they do come on board, will the agents of change by changed?

- 1 Comment

November 2, 2011 by Maya Bernstein

Business Trip

http://www.flickr.com/1flatworld

Six years ago it was evening, and the light came gently through the slats of the hospital window shades, and the room was strangely calm, and it was all so new, and then she was in my arms, a being of radical energy, and I sang to her. Today it was morning of breakfasts and lunches and searching for car keys and rushing and phone calls and singing and dancing of birthday and presents and then of my leaving. Now daytime is flying beneath me is desert before me is evening of working and teaching and she is behind me.

She cried while I applied eye makeup and when I left to catch my flight.

I pinky-promised that I’d try never to travel on her birthday again, but as I sit here tumbling away, I know that this promise didn’t console her. And I know that no matter what I decide or decides me in the future, there will be times when I am not there when she needs me, when she is going in one direction and I in another, when I cannot give her what she needs when she needs it.

As the distance between us grows, in time, in space, I realize that I must learn how to better help her navigate the distances that inevitably arise. Perhaps this is my most important job as her mother.

Today, six years later, I learned something. I write it, share it, so as to attempt to better etch it into my own being, with the hope that it may help me diminish the future distances.

- 2 Comments

October 28, 2011 by Tara Bognar

Of Buses and Borough Park

Image via Wikicommons

Segregating a certain class of people to the back of the bus has an intense resonance for anyone raised on stories of the Black civil rights struggle, Rosa Parks, and the irresistible narrative of how far we’ve come. So it’s not surprising that a story about the quasi-public New York city bus, the B110, where “the women is in the back. The men are in the front” [sic] has spread far and wide from the Columbia University newspaper that ‘broke’ the story.

Blogger Unpious describes the general tenor of the media response: “Like a school of hungry piranhas, the secular media seems to have discovered misogyny in the Chasidic world and they’re having themselves a feast.” He has a thoughtful critique on the dynamics of outside criticism on this insular community:

The outrage of outsiders won’t effect change largely because outsiders don’t seem to actually care about the plight of Chasidic women. Rather, they seem driven by a general distaste for all things Chasidic and, in this case, by the larger symbolism of back-of-the-bus discrimination. To them, Chasidic women are pawns in a larger struggle to root out discrimination everywhere, a worthy cause, no doubt, but one that Chasidic women, by and large, will not care for. Moreover, outsider outrage produces a defensive posture within the Chasidic community – on the part of both men and women – and speaking out against discriminatory practices, even by the tiny minority who might do so otherwise, becomes even more unlikely. I have yet to see those indignant outsiders bother to speak to actual living, breathing Chasidic women (or men, for that matter) to gauge how they feel about it.

- 2 Comments

October 27, 2011 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

A Conversation With Nancy K. Miller

Nancy Miller never meant to become a detective. But the distinguished professor of English literature of English and comparative literature at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and the author of more than a dozen books found herself intrigued by the discovery of a small family archive after her father’s death. A handful of photographs, a land deed, a postcard from Argentina, unidentified locks of hair…What had these things meant to her father? And what did they mean to her? So Miller embarked upon a quest: for people, for places, for meaning. The result, “What They Saved: Pieces of a Jewish Past,” was just published by the University of Nebraska Press. In the interview below, Miller talks with Lilith’s Fiction Editor, Yona Zeldis McDonough, about her new book.

Nancy Miller never meant to become a detective. But the distinguished professor of English literature of English and comparative literature at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and the author of more than a dozen books found herself intrigued by the discovery of a small family archive after her father’s death. A handful of photographs, a land deed, a postcard from Argentina, unidentified locks of hair…What had these things meant to her father? And what did they mean to her? So Miller embarked upon a quest: for people, for places, for meaning. The result, “What They Saved: Pieces of a Jewish Past,” was just published by the University of Nebraska Press. In the interview below, Miller talks with Lilith’s Fiction Editor, Yona Zeldis McDonough, about her new book.

What prompted you to write a book about your ancestral objects? Lots of us have things of this kind but wouldn’t have thought to write about them.

I probably would never have undertaken the research for this book, let alone written it, if I had not received a phone call in the summer of 2000 from a real estate agent in Los Angeles telling me that I had inherited property in Israel from my paternal grandparents—and that he could sell it for me. Not just for me, but all the heirs, which meant my sister and my first cousin (whom I had never met), if he was still alive. I succeeded in locating my cousin in Tennessee. His daughter had begun doing research on the family and had found a website already in place for all the immigrants to America with our family name: Kipnis. I had been resigned to not knowing anything about my father’s side of the family. And suddenly, one discovery led to another and I got caught up in the fascination of the quest to find out everything I could about these mysterious relatives and what had happened to them.

- No Comments

October 26, 2011 by Julie Sugar

Skipping Shabbos and Drawing Lines

http://www.flickr.com/incendiarymind

It’s 4pm, and I am sitting with my friend at a T.G.I. Friday’s in Philadelphia. I have chosen not to think of the day itself as Shabbos. I am skipping Shabbos day, you see; it’s just Saturday.

We’re looking to split an appetizer and then a dessert. She points out something on the menu, and I see that (like almost everything else on the menu) it includes meat. “Oh, I can’t eat that,” I say. She knows that I don’t eat non-kosher meat, but didn’t realize that particular dish wasn’t vegetarian.

I hesitate.

Because what’s the difference when my observance level is in flux lately, anyway? Where is the line? Why don’t I eat non-kosher meat? I decide to not order a dish with meat in it: I don’t want to deal with whatever feelings of guilt I may feel while eating it, or afterwards. Better to explore one big Jewish challenge at a time, starting with Shabbos—one week at a time.

See, I love Shabbos, I really do. I don’t want to give it up. But it is unclear now what the shape of that day will look like… where the lines are. The line used to be halakha, Jewish law, but I am no longer convinced that is the right metric for me for Shabbos, or for the Jewish life I want to live. Frankly, I’m not sure it ever was. I just don’t know, though. Picking and choosing is a slippery slope.

- 5 Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...