February 7, 2013 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

A Conversation with Racelle Rosett

Your stories all center on a group of Reform Jewish community in Hollywood; is this a community you know well from personal experience?

Your stories all center on a group of Reform Jewish community in Hollywood; is this a community you know well from personal experience?

The temple my kids grew up in is nicknamed “Temple Beth Showrunner” because the creators of so many television shows attend. But when you sit in the sanctuary year after year you see that loss is loss. That’s what interested me – that in LA where are lives are so disparate, the temple remained a destination of healing and connection.

There is a moment as an adult when you suddenly deeply understand Shehechianu. When you realize how extraordinary a blessing it is to arrive, sustained at this moment. You are keenly aware of the loved ones who did not arrive with you. You make this journey with your community – it would be unbearable without it.

Jewishly, Los Angeles has an incredibly dynamic scene right now there seems to be a real desire to connect and also a vigorous mission of social action. Sharon Brous an LA rabbi was named one of the most influential rabbis in the country. East Side Jews is an organization that creates gleefully irreverent but deeply spiritual gathering for young Jewish people outside of temple. It’s exciting to see how our Jewish lives inform our daily lives – how relevant and useful these rituals are – even now, even in LA.

Do you feel there is a distinct difference between Jews in say, Los Angeles, and Jews in New York City?

Well, I had Zabar’s flown in for my son’s briss. In LA on Simchat Torah they serve sushi to commemorate the scroll. But lox is lox! I think we are less different than we are the same. We are the same in the ways that most matter. Allegra Goodman’s collection Total Immersion is set in Hawaii, but I think that is the same delight of stepping into a temple in a different country or a different community. If you wait a few moments the Shma will be said and you’ll know who you are.

- 2 Comments

February 6, 2013 by Amy Stone

Let Us Now Praise Non-Jewish Jews

Dispatches from the NY Jewish Film Festival.

(The 22nd New York Jewish Film Festival, presented by The Jewish Museum and the Film Society of Lincoln Center, ran through Jan. 24, 2013. The Ninth Annual Brooklyn Israel Film Festival, ran Jan. 24, 26, 27. For details, visit here.)

[WARNING: If by some long shot you’re planning to see “The Yellow Ticket” do not let this review ruin the plot. Skip to “AKA Doc Pomus.”]

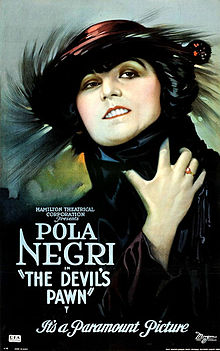

The jaw-dropping happy ending to the 1918 Pola Negri silent film “The Yellow Ticket” (also translated as “The Devil’s Pawn”) is that the super smart and beautiful young Jewess from Warsaw is not Jewish. She’s the love child of the distinguished medical professor whom she’s studying with in St. Petersburg. She then gets to accept the affection of her dashing Russian classmate.

But this OMG-she’s-not-Jewish ending shouldn’t make the film traif. The plot is based on a Yiddish melodrama and is believed to be the earliest film dealing with discrimination against Jews in Czarist Russia.

“The Yellow Ticket” was screened at the NY Film Festival Jan. 10, with a new score by klezmer violinist extraordinaire Alicia Svigals, with Svigals on violin and singing, and Marilyn Lerner on piano.

Amidst the pantomimed over-acting that is the hallmark of many a silent film, Negri plays the brilliant young woman with delicacy, despite the heavy-duty black eye makeup found only on a silent film star or a raccoon.

- No Comments

February 5, 2013 by Mel Weiss

The Creep Factor in “Dress Up America”

It should be admitted that I am not your average, or ideal, consumer. But sometimes, it seems that I am in the majority in looking at a product and asking, What in the name of all that is holy and sane were these people thinking?

Recently, when Facebook and Twitter both blew up with news of the Jewish costumes in the “Dress Up America” line available through Walmart, everyone seemed to be saying what I was say; namely, “Wha?”

Let’s break it down a little. Fast forward past the creep factor of small children in “Rabbi” and “Grand Rabbi” gear, clearly modeled on the love child of an Eastern European rebbe and Ovadia Yosef. Oh, sorry – did I say children? Because I meant boys. Boys dress up as rabbis (or “rabbis”) and girls can dress up as “mother Rachel” or “mother Rivka.” And you know, keep on fast forwarding past the fact that the “mother Rachel” costume includes what appears to be a nun’s habit, and a picture on the costume itself of kever Rahel, Rachel’s tomb, in Bethlehem.

So, what? Boys can be rabbis – even “grand rabbis” – and girls can be foremothers? How is it possible that it’s 2013 and this still somehow scans as normal?

Happily, perhaps, the company’s bizarre gender-enforcement doesn’t only come down on its Jewish or oddly philo-semitic customers. A quick perusal through Wayfair.com – the website of the retailer – reveals discrepancies between the fire fighter’s costume (labeled “boys”) and a Red Cross nurses costume, which wins this week’s disturbing time-machine award. Or the fact that there are separate boys and girls chef costumes, and the girls version has a skirt, not pants. I want to call up all the fierce women on the ragingly popular Food Network shows, and ask them if they find that skirts work better when they’re throwing knives around the kitchen.

Or at least, that’s what my fiancé – female, and a rabbi – suggested I do.

- 1 Comment

December 6, 2012 by Liz Lawler

Choosing to Homeschool

What’s your gut reaction to homeschooling? Did you just wrinkle up your nose?

What’s your gut reaction to homeschooling? Did you just wrinkle up your nose?

I know, I know. You picture creepy misfits from huge families who all wear matching clothes. I used to see the same thing. Then I had a kid and I had to contemplate the hornet’s nest that is NYC schooling. The options aren’t great, so let’s just say we’ve settled on homeschooling for now.

And while I’m quite confident in this choice, I still get pretty evasive when acquaintances ask what preschool my kid will be attending. And with good reason. I get a handful of different reactions from people. 1) By far, the most common concern is whether or not my son will be “properly socialized.” Suggest keeping your kid out of school, and people scrutinize your child’s every “please” and “thank you.” God help you if he goes for too long without a haircut. 2) Some people become defensive and/or deeply suspicious. It’s as if our decision is a de-facto judgment upon theirs, or that we are threatening to unravel NYC’s flawless social fabric. 3) Many women act as if I just dumped my college degree in the shredder. “What about your career? WHAT ABOUT HAVING TIME FOR YOU?”

- 2 Comments

December 6, 2012 by Merissa Nathan Gerson

German and Soldier, Falling in Love

It was two AM on a Sunday evening, and I found myself with a German woman and a male former U.S. soldier on a Tel Aviv beach. My life has a way of scooping me up and placing me in places, beautiful places, with beautiful but complex people. It was no simple après-midnight gathering. It was a post-bar, post-language-class indulgence in English.

It was two AM on a Sunday evening, and I found myself with a German woman and a male former U.S. soldier on a Tel Aviv beach. My life has a way of scooping me up and placing me in places, beautiful places, with beautiful but complex people. It was no simple après-midnight gathering. It was a post-bar, post-language-class indulgence in English.

We were in Israeli Ulpan and we were to speak Hebrew, rak iyvrit. But there were not enough Hebrew words to navigate sensitively the space holding three worlds: one German, one Jewish, one American military all in the state of Israel. We wanted, I wanted, not they to talk about the Holocaust.

I don’t know exactly how or why it happened but we had been honest all night and it was just the three of us and they, the German and the solider, were falling in love, and so by osmosis I was falling in love and I needed, desperately, to unveil my little heart.

That unveiling involved shedding a layer and revealing a giant hole left by a trip to Poland. Beneath a blanket of stars on three folding beach chairs I used their ears and my mouth and I poured a tall glass of Holocaust memory. I told them about my father. I told them about the Siberian labor camps and the displaced person’s camp and I told them about Poland, post-war. I told them about my Jewish family having no place in this world until they arrived illegally in America in 1950 with false names. I told them about my father’s favorite party-wear, his DP camp rations card, and I told them about the graves in Poland, about Belzec and the incomprehensibility of everything I was saying. I told them how I was only beginning to understand, only beginning to let the pain in, just in time to let it out.

The soldier was silent for a very long time, and then the German girl spoke and she cried a little and said she knows, she knows it is unknowable. I realized listening to her that she understood what I understood which was that it was all too much to digest with this mind, this heart, this English language. We needed Hebrew and German, military speech, civilian speech and the words of politics, of religion, and beyond to even start to piece things together. We were learning Hebrew to decode the matrix of horror and its delicate entrance into what had become our supremely non-horrific lives.

- No Comments

December 5, 2012 by Amy Stone

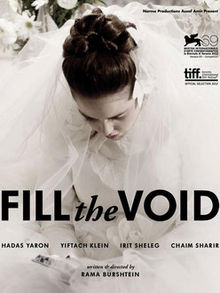

‘Fill the Void’ with Hasidic Dream Men

Park your Jewish feminist preconceptions at the door of this Israeli “insider film” on life within the world of Tel Aviv Hasidim.

Park your Jewish feminist preconceptions at the door of this Israeli “insider film” on life within the world of Tel Aviv Hasidim.

“Fill the Void” (“Lemale et ha’Chalal”) made its U.S. premiere in October at the 50th New York Film Festival, following its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival, where lead actress Hadas Yaron received Best Actress award. This is the story of a young Hasidic woman pressured to marry her brother-in-law after her sister dies in childbirth.

Don’t expect the bitter tale of a teen-ager whose dreams and youth are sacrificed to an ultra-Orthodox society in need of childcare. This first feature film written and directed by 45-year-old Rama Burshtein, a happily Hasidic New York-born Israeli, is gentle, sweet and totally self-contained. The outside world remains outside the close-knit community of well-dressed Hassids with international connections. Clothed in the time warp of a vanished East European Jewry, the men wear white knee socks, silken holiday robes that anywhere else would be luxe bathrobes, and shtreimels (fur hats) the size of lampshades. The wives cover their heads with stylish turbans – silk wrappings in faux leopard prints. But the feeling is anything but antique; this is an observant way of life that’s alive and well.

- 1 Comment

December 5, 2012 by Susan Weidman Schneider

When Our Shoes Hobble Our Freedoms

http://www.flickr.com/uggboy

Tell me what it is about shoes this season.

The photographs I see in the glossy ads actually scare me — 19-inch heels on 5-inch platforms. (I exaggerate only slightly.) The shoes on women’s feet would be cartoonish — if only they were in a comic strip.

Look, shoes have meaning. Just check out all the recent books about footwear and websites like Shoe Hero. We know about foot binding. About the iron shoes along a Danube promenade as a memorial to the Hungarian Jews forced to remove their footwear before being shot. About traditional Judaism’s halitza ceremony, in which a childless widow throws a specially designated “halitza sandal” at her unmarried brother-in-law, thus releasing him from his obligation to marry her and continue his brother’s line.

- No Comments

October 23, 2012 by Sheva Zucker

Candles of Song: Rokhl Korn

Yiddish poems about mothers, in memory of my mother, Miriam Pearlman Zucker, 1914-2012.

Photo of Rokhl Korn

Rokhl (Haring) Korn (1898-1982) was born near Podliski, East Galicia on a farming estate. Her love and knowledge of nature is reflected both in her poetry and prose. She was educated in Polish and started writing poetry at an early age in Polish. At the start of the First World War, she and her family fled to Vienna, then returned to Poland in 1918 and lived in Przemysl until 1941. Korn’s first publications were in Polish in 1918 but pogroms against the Jews of Poland after the war led her to write in Yiddish, though she had to be taught to speak, read and write the language by her husband Hersh Korn whom she married in 1920. Her first Yiddish poem appeared in the Lemberger Tageblatt in 1919.

In 1941 Korn fled to Uzbekistan and then to Moscow, where she remained until the end of the war. Her husband, her mother, her brothers and their families all perished in the Holocaust. She returned to Poland in 1946 and in 1948 immigrated to Montreal, Canada where she lived and remained creative until her death. She was a major figure in Yiddish literature and in 1974 she won the prestigious Manger Prize.

Korn was extremely prolific. Her works include: Dorf, lider (Village, poems). Vilna: 1928; Erd, dertseylungen (Land, stories).Warsaw: 1936; Royter mon, lider (Red Poppies, poems). Warsaw: 1937; Heym un heymlozikayt, lider (Home and Homelessness, poems). Buenos Aires: 1948; Bashertkayt, lider 1928–48 (Fate, poems 1928–48). Montreal: 1949; Nayn dertseylungen (Nine Stories). Montreal: 1957; Fun yener zayt lid (On the Other Side of the Poem). Tel Aviv: 1962; Di gnod fun vort (The Grace of the Word) Tel Aviv: 1968; Af der sharf fun a rege (The Cutting Edge of the Moment). Tel Aviv: 1972; Farbitene vor, lider (Altered Reality, poems). Tel Aviv: 1977.

Here, Doyres, by Rokhl Korn, read by Sheva Zucker:

- No Comments

October 23, 2012 by Sheva Zucker

Candles of Song: Asya

Yiddish poems about mothers, in memory of my mother, Miriam Pearlman Zucker, 1914-2012.

Photo of Asya

Asya Kuritsky-Guy (1932-2009) was born in Vilna. Her father was a painter who wrote plays that were never produced. During the Second World War she and her parents fled to Soviet Russia. At the age of eight she began writing poetry in both Russian and Yiddish. When she was repatriated to Poland after the war she worked in an orphanage and created literature – poems and plays – for the children. In 1951 she emigrated to Israel and studied in a drama school there. For a brief time, from 1956-1856, she acted in the Habimah theatre. From 1948 on her poetry was published in a number of publications, in Poland, America and Israel. None other than the great poet Yankev Glatshteyn wrote the foreword to her debut volume Tsvyagn-tsiter (The tremble of Branches). In Israel she published the books Tsvaygn-tsiter, 1972 and Nit kin albatros (Not an albatross), 1981.

Here, Mame, by Asya, read by Sheva Zucker:

- No Comments

October 18, 2012 by Sheva Zucker

Candles of Song: Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman

Yiddish poems about mothers, in memory of my mother, Miriam Pearlman Zucker, 1914-2012.

Photo of Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman

Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman (1920 – ) was born in Vienna, her mother was a remarkable traditional folksinger and her father, a passionate Yiddishist. She and her family left to settle in Czernowitz, Ukraine (then Romania), when she was a young child. Thinking she wanted to be an artist, Schaechter-Gottesman went to Vienna to study art but was forced to return to Czernowitz when the Germans invaded Austria in 1938. In 1941 she married a medical doctor, Jonas (Yoyne) Gottesman, and together they lived out the war in the Czernowitz Ghetto along with her mother and several other family members. She, her husband and daughter settled in New York in 1951.

Schaechter-Gottesman’s first book of poetry, a children’s book, Mir Forn (We’re Travelling) appeared in 1963. Her books, nine in total, have appeared regularly since then. They include poetry for adults, children’s books and song books. Her most recent book is Der tsvit fun teg: Lider un tseykhenungen (The Blossom of Days: Poems and Drawings), 2007. She has recorded three CDs of her songs and one recording of folk songs. Beyle has played a central role in reviving and inspiring interest in Yiddish song and poetry among a new generation of artists, and her songs have been performed by many of the major names in Yiddish music. She is the only Yiddish poet ever to be awarded a National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, the top honor for folk arts in the United States.

Here, S’letste Bletl, by Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman, read by Sheva Zucker:

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...