October 8, 2013 by Susan Weidman Schneider

When You Can’t Afford a Diaper…

Joanne Samuel Goldblum, photographed by Gale Zucker

During this government shutdown, there are now insurmountable obstacles to accessing many of the vital human services that so many depend upon–food aid to women, infants and children (WIC), for example. The shutdown is not just a matter of government employees losing wages hour by hour (bad enough) but of the grievous plight of people–largely women, in fact–whose very food for survival is in jeopardy. And these benefits at their best are too often insufficient for the people who need them most. Here is one woman who has for 10 years taken on an often unrecognized–but enormous–expense for families today.

“Once you start noticing, the need is everywhere.” So says Joanne Samuel Goldblum, founder and president of The National Diaper Bank Network (diaperbanknetwork.org), the largest diaper bank organization in the nation. She created this innovative nonprofit in New Haven, CT, 10 years ago. This year, through the National Diaper Bank Network, she distributed more than 15 million free diapers to needy families across the country through a network of local diaper banks. According to the organization’s website, nearly 30 percent of low-income families cannot afford diapers.

Honored widely for her pioneering work, Goldblum told Lilith that her early experiences as a social worker, seeing a need that is often quite invisible, moved her to relieve the pain of babies and children who have to spend all day in a urine-soaked diaper — and the shame and depression their mothers suffer (yes, most often the mothers) when they have to put a kid to bed in a dirty diaper because they can’t afford clean ones. Or can’t go to work because they don’t have the money for the diapers you need to send to daycare. “And you are not allowed to pay for diapers on food stamps!” said Goldblum.

“With diapers, once you see the need you start to see it everywhere — towels, shampoo, soap, toilet paper. When you start to think about what happens to families when you cannot afford these things… oral hygiene problems because they don’t have toothpaste or kids going to school dirty because there is no laundry detergent….

“We are taking about diapers, but the bigger picture we are talking about is poverty, and about kids in America — and we manage to ignore this to a large degree.”

Goldblum says her mother, Ellen Samuel Luger, a social worker active in reproductive rights, is her model for activism. “It’s striking to me how many social workers are Jewish women! This fits incredibly well with what you learn as a Jew about social justice. Tikkun Olam is what the rabbi talked about” in the New Jersey Reform congregation where she grew up.

So why are “churches” and not “synagogues” mentioned on The Diaper Bank Network’s website? Although there are synagogues and temples that run diaper drives, Goldblum said, “I have had less luck getting in to speak at synagogues than at churches. It likely has more to do with the ways churches and synagogues do community outreach. We certainly get a lot of support from people affiliated with synagogues. The Diaper Bank Network has been trying really hard to find ways to connect with organizations like JCCs and early childhood programs.” Not surprisingly, Goldblum notes that the biggest category of individual supporters is “young parents — and grandparents.”

One of the seemingly simple policy changes Goldblum advocates is for social-service agencies to have a line item for diapers, which they give out frequently. “They only call them ‘incidentals’ in their budget, though they do spend money on these things. It’s important to name them, so people notice them.”

- No Comments

October 2, 2013 by Chanel Dubofsky

Putting My Mother Back Together

Really, I am just trying to put her back together. The woman I knew as my mother was dismantled, by illness and by fear and trouble, but there’s the person I didn’t know, ever, and I am trying to find her.

I made one phone call, to G, my cousin, the daughter of one of my grandmother’s sisters. I sent one email, to my uncle. It took me a long time to do this, and I finally managed it in one of those middle of the night seizures of bravery. All you require is one moment of insane bravery, someone wrote. Or at least something that can pass for insane bravery.

The email I wanted to send to my uncle, my mother’s only brother, was something like, “Can you tell me what the hell happened?” Instead, it was kind of desperate, admitting to him that I had never asked her certain questions while she was alive (How had she met my father? Why hadn’t she gone to college after she’d been accepted? What else had happened to her in her life?), and hoping he could tell me something. The specific questions I had had no longer seemed terribly important. Anything he could do to fill out my hollow picture would do.

- 1 Comment

Overheard in New York, The Lilith Blog

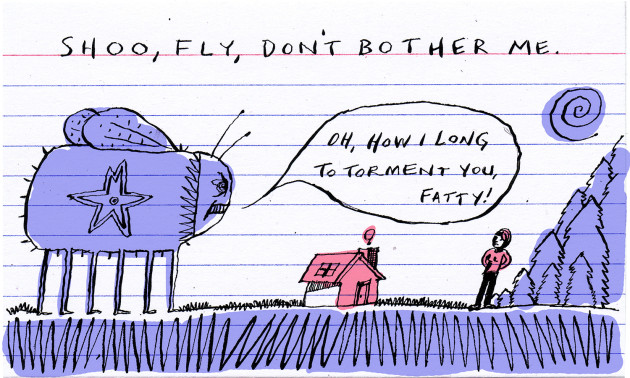

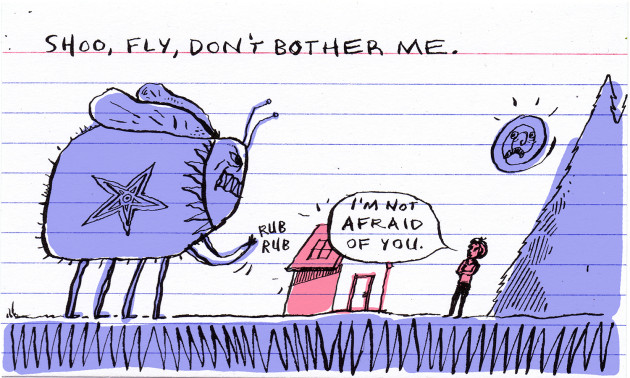

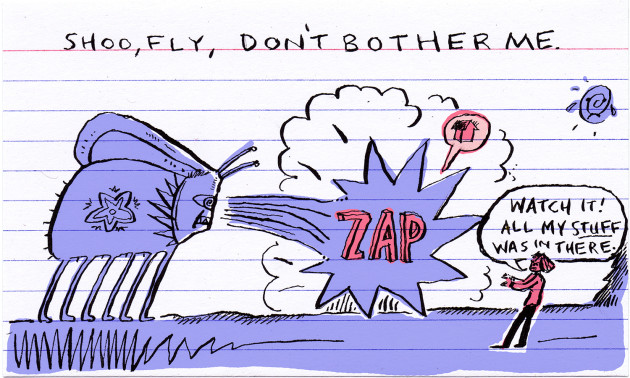

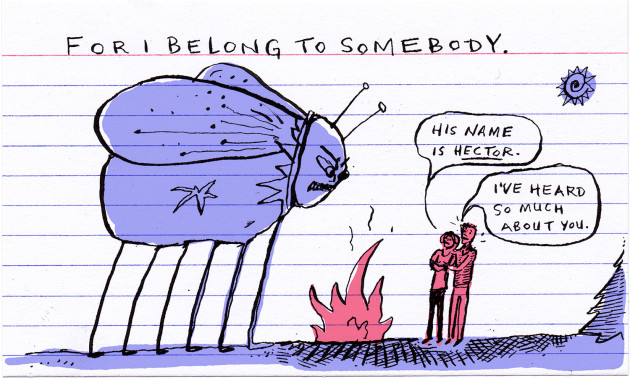

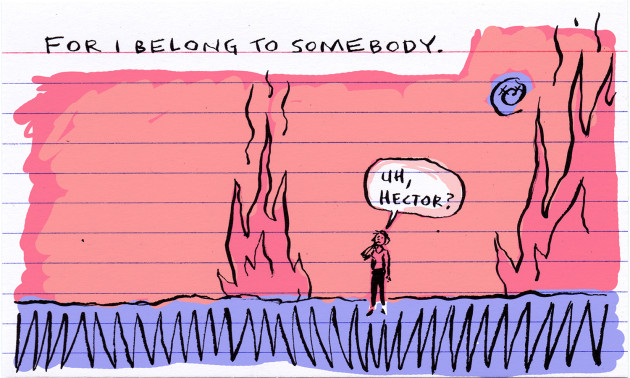

September 25, 2013 by Liana Finck

Don’t Bother Me

- No Comments

September 24, 2013 by Maya Bernstein

Autumn Moms

Another season of frog catching, ice cream licking, wet green hill rolling, firefly chasing, and lake swimming has come to an end. The long days are becoming shorter, and the first blushes of fall are painting a faint tinge of reds, yellows, and oranges into the lush green canopies. The kids are back to school, to the months of routine, rushed mornings, and scheduled afternoons. We’re about to launch them into another year of growth, charting their progress, measuring their successes, and cheering them on as they trip, falter, and get back up.

Another season of frog catching, ice cream licking, wet green hill rolling, firefly chasing, and lake swimming has come to an end. The long days are becoming shorter, and the first blushes of fall are painting a faint tinge of reds, yellows, and oranges into the lush green canopies. The kids are back to school, to the months of routine, rushed mornings, and scheduled afternoons. We’re about to launch them into another year of growth, charting their progress, measuring their successes, and cheering them on as they trip, falter, and get back up.

It always amazes me how much kids grow and change over the summer. They shine out in all directions, limbs elongating, hair tugged down by gravity, bones shooting up to the stars. My five year old learned to bike and swim; her big sister to roller skate and shower by herself; and the three year old was toilet trained. They are all working on keeping their passionate emotions in check when they over boil, and sharing their feelings in open, productive ways. I once attended a professional conference, where, during the initial icebreaker, we were asked to share something new we had learned to do over the course of the year. Many of the participants struggled to think of something. One of the participants had brought her young son with her, and when it was his turn to share, he started rattling off a list: I learned to play basketball, tie my shoes, count by 7s, play the piano, cook an egg, walk my dog, wash my dishes…his list went on and on. We all can grow and change; kids do it at a relentless pace, and without hesitation.

- 2 Comments

September 23, 2013 by Rori Picker Neiss

Laws Aren’t Beautiful. People Are Beautiful.

When I think of Rosh Hashanah, I am immediately struck by the drama of the Day of Judgment. I think of a time of introspection, of melodic prayers and inspiring poetry, of sweet foods eaten with family and close friends.

When I think of Rosh Hashanah, I am immediately struck by the drama of the Day of Judgment. I think of a time of introspection, of melodic prayers and inspiring poetry, of sweet foods eaten with family and close friends.

I do not think of sex.

That is, I never used to think of sex in relation to Rosh Hashanah, until a friend sent me an article which attempted to link the two. In an elegant and vivid piece, Merissa Nathan Gerson characterizes honey, a food prevalent as we celebrate the New Year, as the creative result of the unbridled sexual energy of the abstinent worker bees. Suddenly, dipping the apple in honey was no longer a simple act to symbolize a sweet new year.

Gerson takes her point further, though, comparing the abstinence of the bees to the abstinence practiced by Jewish couples who observe the laws of niddah, often translated (poorly, in my opinion) as “family purity” or sometimes “menstrual purity.” For couples who practice niddah, the laws prohibit intercourse approximately two weeks of every month– from when a woman sees the onset of her period until after she has counted seven days of absolutely no blood. For many, the laws also include prohibitions of sleeping in the same bed, any form of touch, and even passing items directly from one person to the other. This system, argues Gerson, causes the sexual energy to build up, giving couples a store of vivacity and enthusiasm that can be channeled into enhancing other areas of Jewish life.

“For Jewish couples that observe the laws of niddah, half the month is then reorganized, redirecting sexual energy into the community, into the work of protecting the “queen”—the sanctity of the Sabbath. During the periods of abstinence, this energy is used to perform acts of tikkun olam, study Torah, or generally apply oneself toward the greater good of the Jewish collective. While bees produce honey, I like to think of Jewish laws around sex as yielding something, too: a sweet substance that comes in the form of tzekadah, of building community, and making the world brighter through devotional practice.”

My challenges to this argument are almost too numerous to count. Are we incapable of making a beautiful Shabbat dinner when we are permitted to have sex? Do we assume that all our energy should be, or is, channeled to sex at other times of the month? Do we truly live in this binary in which we have a limited amount of energy that can either be applied towards sex or to improving the world? And, if so, do people who do not have prohibitions on having sex do less to improve the world around them? Do people who are not in relationships have a greater obligation of tikkun olam– repairing the world? Is there a way to measure our sexual energy to ensure that at times when we are niddah we are exerting the proper amount of energy into the Jewish community? Are pregnant women and nursing mothers who are amenorrheic exempt from contributing to the improvement of the world and the betterment of the Jewish community? Do we consider women who choose to skip periods using hormonal birth control methods also to be exempt, or would we still consider them obligated to apply themselves toward the greater good of the Jewish collective since their absence of a period is chemical? Or, like niddah, does one’s commitment to Torah study and tikkun olam only begin when one sees the flow of blood?

- 2 Comments

September 18, 2013 by Mel Weiss

Dispatches from Lesbian Vacationland

As the new school year begins, I want to take one moment to reflect on the summer. And my biggest lesson this summer? To be honest, it was about Jewish education. And who says a Jewish education can’t be fun? (Okay, it’s possible that I did, for much of my childhood. That was back in an earlier period for me before I fell in love with Judaism, a rabbi, and the small town where she landed a pulpit – in that order. These days, since she’s the basically village rabbi and I work as the Jewish educator, we not-so-jokingly call ourselves the Lesbian Chabad.)

As the new school year begins, I want to take one moment to reflect on the summer. And my biggest lesson this summer? To be honest, it was about Jewish education. And who says a Jewish education can’t be fun? (Okay, it’s possible that I did, for much of my childhood. That was back in an earlier period for me before I fell in love with Judaism, a rabbi, and the small town where she landed a pulpit – in that order. These days, since she’s the basically village rabbi and I work as the Jewish educator, we not-so-jokingly call ourselves the Lesbian Chabad.)

The Lesbian Chabad, as I’ve mentioned, is stationed up in Maine – which in the winter months does a striking imitation of the Eastern European shteppe from which we both hail. Come summer, though, this place magically morphs into Vacationland, and you’d think there’s not a lot of room for Jewish learning in Vacationland.

You’d be wrong, however, and vastly underestimating both the efforts of my wife R. and myself – and the absolute love of Judaism our Hebrew school kids have up here (not to mention the devotion their parents have to making sure they have Jewish experiences as often as possible). They so love spending time “doing Jewish,” whether it’s in the single room where we teach several grades of Hebrew school at once, at synagogue, on Shabbat hikes – whatever, wherever, our kids are in. They’re an educator’s dream.

- No Comments

September 17, 2013 by Merissa Nathan Gerson

Sex in Silverlake

Leave it to feminist power-Jew Jill Soloway (Six Feet Under, United States of Tara) to take a sex worker and have her inadvertently revive a Silverlake couple’s Jewish practice. This is ultimately what happens in Soloway’s first feature film, “Afternoon Delight” which just came out in theaters. The film is about a sexless Los Angeles marriage and the idea to revamp the couple’s bedroom by heading to a strip club. Of course, the wife woos the lap-dancing stripper, McKenna, into moving in as “the nanny” and proceeds to learn from her about the world of sex work, not to mention the world of receiving actual tender care.

Leave it to feminist power-Jew Jill Soloway (Six Feet Under, United States of Tara) to take a sex worker and have her inadvertently revive a Silverlake couple’s Jewish practice. This is ultimately what happens in Soloway’s first feature film, “Afternoon Delight” which just came out in theaters. The film is about a sexless Los Angeles marriage and the idea to revamp the couple’s bedroom by heading to a strip club. Of course, the wife woos the lap-dancing stripper, McKenna, into moving in as “the nanny” and proceeds to learn from her about the world of sex work, not to mention the world of receiving actual tender care.

What proceeds is a visible split between the life of Jewish community and Jewish stay-at-home moms, and the world of sex work, of McKenna’s job as a prostitute and as stripper which affords the lead, Rachel, an exit from her stifled life. The Jewish community center and Jewish school are the meeting points for Rachel and the other super-moms, and their fundamental role is the role of giver, of caretaker, of being mothers and community builders. Sex and sexuality, the way Soloway draws it in this film, is notably separate from this world of Jewish female as nurturer.

Rachel’s rat pack of four moms are repeatedly seen entering and exiting their children’s school in unison, a la “Mean Girls,” a la “Heathers,” a la every high school film that ever rocked. These are the girls grown up. These are the housewives who once wanted to be big writers. These are the modern day “stepfords,” and the only remedy in this film to the dissatisfied life of Rachel is exiting to a world where sex means money and ownership, where sex means power.

- No Comments

September 12, 2013 by Liz Lawler

Jews, Drugs, and the Muck of Daily Life

You are probably as mired in the muck of daily life as I am. I can hardly remember the last time I caught an inkling of magic or mystery. Having kids, a job, a dog to walk, all makes transcendence a bit of a reach. There is just something tugging at my sleeve at every turn. But it’s that very cacophony that makes the need for transcendence so pressing. And as we approach the High Holidays, this quandary has shifted to the front of my mind. This is supposedly a time of reflection, a reset button for the year. I generally take a pretty utilitarian view of religion. So, finding links between the body, the spirit and the psychotherapeutic appeals to me. Spiritual practice and religious connection can be a healing salve in a fragmented world, and fractured personal experience of said world. But how does one bridge the gap between the mundane and the sacred, between the body and mind? And since I’m so very busy and important, do I get to take a shortcut? I find myself tempted, in my haste towards bliss, to reach outside of myself for help from “my friends.” All of which has got me wondering about Jews and drugs, and the magical mystery tour that Judaic practice can be.

You are probably as mired in the muck of daily life as I am. I can hardly remember the last time I caught an inkling of magic or mystery. Having kids, a job, a dog to walk, all makes transcendence a bit of a reach. There is just something tugging at my sleeve at every turn. But it’s that very cacophony that makes the need for transcendence so pressing. And as we approach the High Holidays, this quandary has shifted to the front of my mind. This is supposedly a time of reflection, a reset button for the year. I generally take a pretty utilitarian view of religion. So, finding links between the body, the spirit and the psychotherapeutic appeals to me. Spiritual practice and religious connection can be a healing salve in a fragmented world, and fractured personal experience of said world. But how does one bridge the gap between the mundane and the sacred, between the body and mind? And since I’m so very busy and important, do I get to take a shortcut? I find myself tempted, in my haste towards bliss, to reach outside of myself for help from “my friends.” All of which has got me wondering about Jews and drugs, and the magical mystery tour that Judaic practice can be.

On the one hand, Judaism is largely non-ascetic. One of the more charming qualities of this religion is its perpetual celebration of the here and now, how Jews embrace the material world in all of its flavorful glory. Kashhrut is not about denial, it’s an awareness raising mechanism. And alcohol is written into the liturgy. What’s a Passover Seder or a Purim spiel without the steady flow of wine? There is a religiously sanctioned time to come unhinged, disconnect, and lose yourself in a lushly indulgent moment. So can we take this from disconnection and argue that substances can be used to re-connect? Instead of escapism, maybe they can motivate a grounding or rooting action, underscoring the re-absorbing effects of the holiday season. In this sense, the corporeal sphere of the body becomes (as Tantrikas believe) a field of discovery, a way of experiencing the world and G-d, merging with the organic whole. I guess, ultimately, I’m after a somatic experience of religion, something I don’t usually associate with Judaism.

Can I take this as license to use psychoactive substances? I’m not talking cocaine or heroin here. But I would love an excuse to eat a fistful of mushrooms and go floating through the park. It would seem that so do a lot of other Jews.

- No Comments

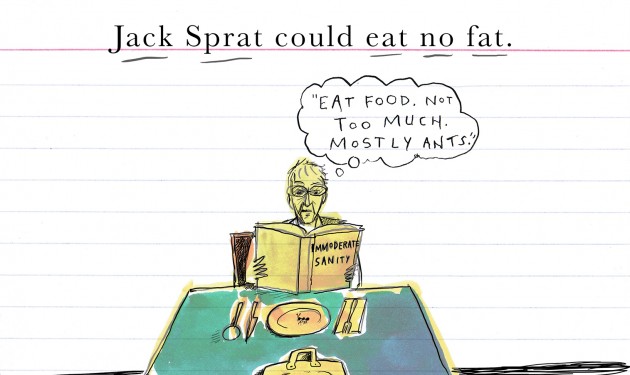

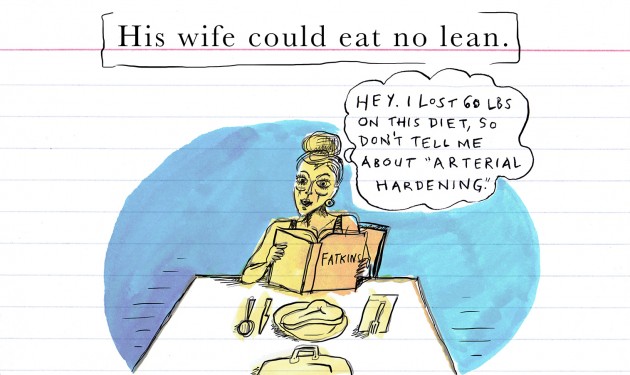

September 11, 2013 by Liana Finck

Eat No Fat

Liana Finck received a Fulbright Fellowship and a Six Points Fellowship for Emerging Jewish Artists. She is finishing a graphic novel, forthcoming from Ecco Press, based on the Bintel Brief, a beloved Yiddish advice column that was published in the Forward newspaper beginning in 1906.

- No Comments

September 10, 2013 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

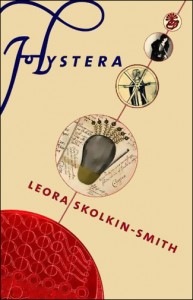

Hystera

Originally published in 2011 by Fiction Studio Books, Leora Skolkin Smith’s Hystera (winner of the Global E-Books Award and the USA Book Award in Fiction) will be re-released on September 10 by The Story Plant. In this slim but brutal novel, Lillian Weill blames herself for the fatal accident that takes her father away. Tripping through failed love affairs and doomed friendships, all Lilly wants is shelter and peace. She retreats into a world of delusion and lands in a New York City psychiatric hospital; Hystera charts her journey into the darkest hell of self—and back again. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talked with Smith about Patty Hearst, mental illness and the old city of Jerusalem.

Originally published in 2011 by Fiction Studio Books, Leora Skolkin Smith’s Hystera (winner of the Global E-Books Award and the USA Book Award in Fiction) will be re-released on September 10 by The Story Plant. In this slim but brutal novel, Lillian Weill blames herself for the fatal accident that takes her father away. Tripping through failed love affairs and doomed friendships, all Lilly wants is shelter and peace. She retreats into a world of delusion and lands in a New York City psychiatric hospital; Hystera charts her journey into the darkest hell of self—and back again. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talked with Smith about Patty Hearst, mental illness and the old city of Jerusalem.

Yona Zeldis McDonough: This is an unflinching portrait of mental illness; what drew you to the subject?

Leora Skolkin Smith: I was drawn to writing about mental illness by the popular medical and cultural presentations of it. I felt that the continual oversimplifications in the media threw more darkness than light onto this disturbing and beguiling state of human behavior and ultimately silenced the cries from those in the throes of it. In recent years, the use of drugs such Prozac have been described in memoirs and accounts of depression but I felt this was only a partial, inadequate answer. I wanted a deeper exploration, one that was not based on easy resolution or being “fixed,” but instead engages philosophical and sexual questions of existence itself, as well as questions about identity and intimacy that transcend our purely medical and limited understanding. I wanted to show that mental illness is part of a continuum of human experience throughout history.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...