The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

September 24, 2012 by Helene Meyers

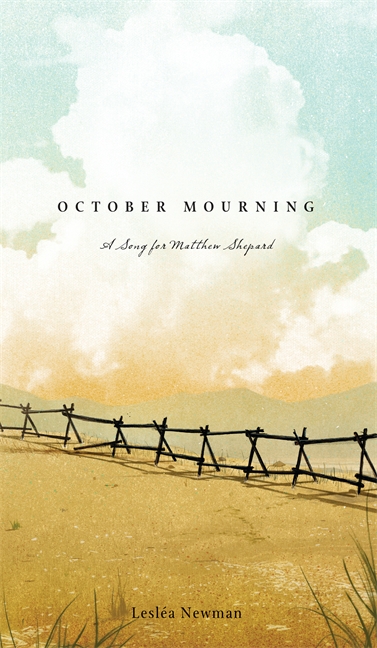

Memory and Teshuva: A Review of October Mourning

Leviticus 18, which deems men lying with men an abomination, has traditionally been part of the Yom Kippur service. Many congregations today opt for a substitute for this oft-quoted but underhistoricized text that has contributed to diverse forms of religious and secular homophobia. Whether we reject, historicize, or transform the meaning of these words that have hurt, we should relish opportunities to communally atone for complicity with traditional and contemporary forms of hate. Lesléa Newman’s October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard, scheduled to be released on Erev Yom Yippur, is a “historical novel in verse” that inspires cultural memory and teshuva.

Leviticus 18, which deems men lying with men an abomination, has traditionally been part of the Yom Kippur service. Many congregations today opt for a substitute for this oft-quoted but underhistoricized text that has contributed to diverse forms of religious and secular homophobia. Whether we reject, historicize, or transform the meaning of these words that have hurt, we should relish opportunities to communally atone for complicity with traditional and contemporary forms of hate. Lesléa Newman’s October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard, scheduled to be released on Erev Yom Yippur, is a “historical novel in verse” that inspires cultural memory and teshuva.

This slim but powerful volume of poems is divided into four parts. The prologue, a single poem titled “The Fence,” gives voice and perspective to an inanimate object, an innovative feature of this collection reminiscent of the talking bus and washing machine in Tony Kushner’s Caroline, or Change. After Matthew Shepard’s persecutors beat him, they tied him to a fence and left him for dead. This poem personifies the fence, clearly identified with the victim, before it became part of a hate crime: “will I always be out here/exposed and alone?”

Part One poetically represents the scene and context of the crime as well as the immediate aftermath as Shepard lay dying, first tied to the fence for 18 hours and then in a hospital intensive care unit. “Raising Awareness” reminds us of the heartbreaking irony that Shepard was killed as Gay Awareness week on the University of Wyoming’s campus was about to commence; “A Sorry State” furthers the irony that gay citizens “may not be safe/at home” in Wyoming, the so-called “Equality State.” The truck that Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson drove, the road that they took, the rope that they used to lash Matthew to the fence, the armbands that members of the community wore to remember Shepard and to be counted as resisters to hate, the candles that “faded” from vigil “into mourning,” and the tree used for the box holding Matthew’s ashes are all given their poetic say here. Likewise, Newman uses the historical record to imagine the human horror that accompanied intimate knowledge of this crime. Seemingly seasoned and thus hardened professionals—a police officer, a doctor, a journalist, and an ICU housekeeper—bear witness to the atrocity against “that boy,” “someone’s child.” The fence who “held him all night long” and the cat who spent the night wondering “where is my boy?” attest to the materiality of the human body who was not only the object of hate but also a warm and loving subject.

Lives transformed by Matthew Shepard’s death form the core of Part Two. The old fence, which by the end is “gone but not forgotten,” declares that “being a shrine/is better than being/the scene of the crime.” In “The Cop,” a representative of the law simultaneously chronicles and disavows his own habitual hate speech. While Shepard’s death had a closeting effect on some, others proclaimed “I’m gay and it could have been me.” The unrepentant include homophobic protestors at Shepard’s funeral and frat boys who create an effigy of Shepard in the form of a scarecrow marked gay. But “A Chorus of Parents” provides a powerful counterpoint. The refrain of that poem, “I called my son,” functions as an act of contrition for a litany of parental hate crimes: “chewed out kicked out threw up/ on hung up on turned my back on sat shivah for lied about/denied deserted abandoned.” And the brilliant simplicity of a judge who denies the so-called gay panic defense by declaring “there was someone gay and panicked that night/but that someone wasn’t you” makes readers forgive Newman’s occasional overdoing of the word play.

“Pilgrimage,” the poem that serves as the volume’s epilogue, is a prayer uttered by one who makes the journey to a new fence that functions as both a memorial and an affirmation of omnipresent beauty. Newman’s capacious vision is underscored by the religious syncretism embodied in this final verse for Shepard.

Like Newman’s now-classic short story “A Letter to Harvey Milk,” October Mourning does the work of preserving the atrocities of history while firmly offering a vision of choosing life. Refusing to let Shepard fade into oblivion, abstraction, statistic, or symbol, Newman here reminds us that the impulse to repair the world requires imagination as well as concrete memory.

Helene Meyers is the author of Reading Michael Chabon and, most recently, of Identity Papers: Contemporary Narratives of American Jewishness.

Please wait...

Please wait...