Author Archives: Yona Zeldis McDonough

July 3, 2012 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

A Conversation With Dawn Raffel

Dawn Raffel is a brilliant miniaturist. From her exquisitely crafted short stories (In the Year of Long Division, Further Adventures in the Restless Universe) to her slender but ice-pick sharp novel (Carrying the Body), her canvas may be restricted but it is never slight; Raffel finds big meaning in the seemingly small, be it word, gesture or in, the case of her newest book, object. That book, fittingly called The Secret Life of Objects, is a collection of prose poems/love songs/tributes to the stuff—a mug, a pair of lamps, a sewing box, a ring—that make up the warp and woof of her daily life. Raffel answered questions posed by Lilith’s fiction editor, Yona Zeldis McDonough, about the genesis of her newest collection, where she finds inspiration and the surprises that she uncovered when she was willing to probe just a little bit deeper.

Dawn Raffel is a brilliant miniaturist. From her exquisitely crafted short stories (In the Year of Long Division, Further Adventures in the Restless Universe) to her slender but ice-pick sharp novel (Carrying the Body), her canvas may be restricted but it is never slight; Raffel finds big meaning in the seemingly small, be it word, gesture or in, the case of her newest book, object. That book, fittingly called The Secret Life of Objects, is a collection of prose poems/love songs/tributes to the stuff—a mug, a pair of lamps, a sewing box, a ring—that make up the warp and woof of her daily life. Raffel answered questions posed by Lilith’s fiction editor, Yona Zeldis McDonough, about the genesis of her newest collection, where she finds inspiration and the surprises that she uncovered when she was willing to probe just a little bit deeper.

Did you know you were writing a book from the outset?

The whole thing happened very fast. One morning I was drinking coffee from the mug I always take from my cupboard, even though I have a dozen other mugs. I go straight to that one because I took it from my mother’s house after she died, and for me it contains not only coffee but also a whole story about my mother and my aunt. Then I realized that I have a house full of objects like this—things that have a secret personal value that far transcends their surface worth. I wrote them all down very quickly, resisting the urge to over-analyze; it felt like creating a watercolor where you don’t want to muddy things with too much revision. When I was done I saw that what I had written was a book and that it told a life story.

How did you go about organizing these pieces?

I wrote these in the exact order you see them in the finished book, which was intuitive. At one point, an editor asked me to organize the book chronologically, ordering the objects by when I received them. For me, that effort fell flat, I think because so many of the objects are saturated with stories from multiple generations, and in part because memory and feeling simply aren’t linear.

- No Comments

May 2, 2012 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Secret Agent Barbie

Photo via Mattel

Well, Barbie’s gone and done it again. Yes, the petite, plastic plaything has proved, once more, that she’s hardly a retrograde relic. Far from it. Barbie’s on the cutting edge—where, as a matter of fact, she has been since her inception in 1959.

Coming this summer, Mattel will bring out the Barbie Photo Fashion, a brand-new doll with an LCD implanted in her impressively toned tummy. A lens in her back allows her user—almost always a girl—to take pictures with the doll. In a word: Brilliant. Instead of the bimbo blonde who passively receives the male gaze, this new Barbie channels and harnesses nascent female power, by encouraging play of an entirely new kind. Yet again, Barbie has become a vessel and conduit, tapping into the inchoate desires of girls, and giving those desires a comprehensible form of expression in the world.

But to those of us who have known and loved her over the past five plus decades (and I count myself at the top of this list), there is nothing fundamentally surprising about this news. Barbie has always been a secret agent, a force for subversion and empowerment masquerading as a harmless, leggy pin up.

- No Comments

April 30, 2012 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

A Conversation With Debra Spark

Debra Spark is a bit of a fabulist—her stories skirt the tantalizing territory between what’s real and what’s imagined. In this new collection, The Pretty Girl, Spark’s imagination creates a group of stories that are wholly off beat. She talks to Lilith’s fiction editor, Yona Zeldis McDonough, about where she gets her inspiration, her attraction to the visual arts and her fascination—and occasional frustration—with toy theaters:

Debra Spark is a bit of a fabulist—her stories skirt the tantalizing territory between what’s real and what’s imagined. In this new collection, The Pretty Girl, Spark’s imagination creates a group of stories that are wholly off beat. She talks to Lilith’s fiction editor, Yona Zeldis McDonough, about where she gets her inspiration, her attraction to the visual arts and her fascination—and occasional frustration—with toy theaters:

In your linked short stories you create radically different characters, settings and even time periods in each of your stories. Can you say more about this decision?

I wrote these stories over a very long period of time, so that may be part of the answer. I actually think of the stories as connected, despite the variety, since many of them circle around the theme of art and deception.

You have written both novels and stories; do you have a preferred form?

I think I like novels better, since with a novel you only have to think up a new idea every few years, but with stories you have to do it ever few months!

The freshness and originality of your dialogue is really notable. Do you have any interest in writing a play or any other dramatic form?

Thank you. I love the theater, and I would love to write a play at some point, but I just don’t think I have the skills. I frequently go to the theater here in Portland, Maine, and whenever I do, I am newly amazed. Often when I know a play’s conceit in advance, I try to imagine how things will unfold, before I actually see the play. Invariably, what is to come is far richer than what I am able to imagine.

- No Comments

March 1, 2012 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

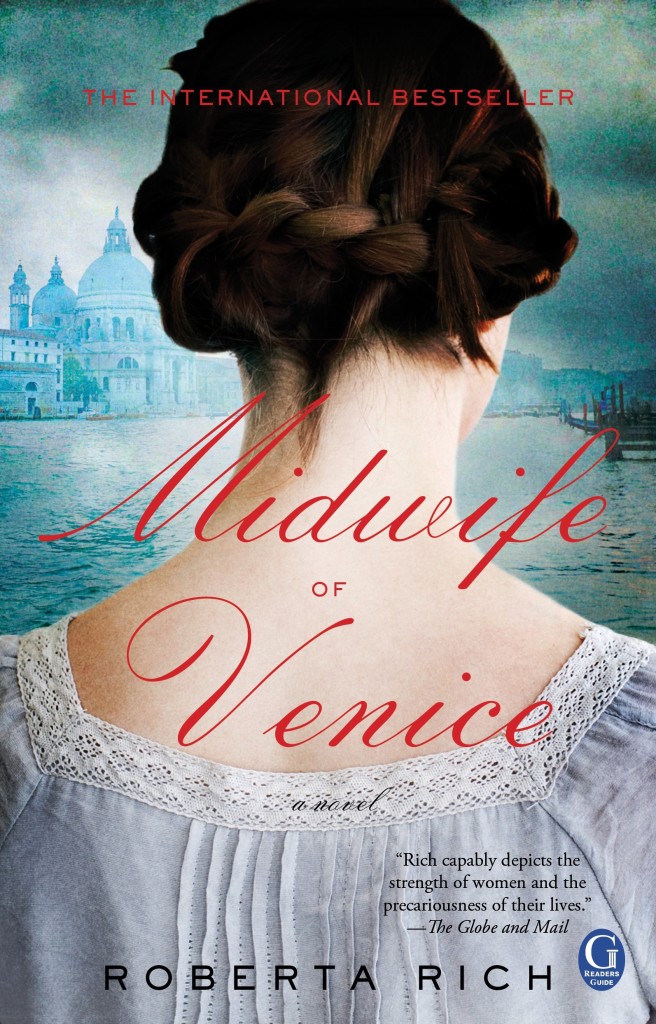

A Conversation With Roberta Rich

Renowned throughout Venice for her gift at coaxing reluctant babies from the their mothers’ wombs, Hannah Levi, a Jewish midwife, is much in demand. But when she receives a summons from a wealthy Gentile count to attend his wife, she is torn about what to do. Does she defy Papal edict that forbids Jews from rendering medical treatment to Gentiles? Or does she try to alleviate the suffering of this unknown woman, and in so doing, earn the money to pay her husband’s ransom? These are the questions raised by “The Midwife of Venice,” the first novel by former lawyer Roberta Rich. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough had some questions of her own, and she sat down with author Rich to find out more about birthing practices in the 16th century, the transition from lawyer to novelist and what life was like in the Jewish ghetto of Venice.

Renowned throughout Venice for her gift at coaxing reluctant babies from the their mothers’ wombs, Hannah Levi, a Jewish midwife, is much in demand. But when she receives a summons from a wealthy Gentile count to attend his wife, she is torn about what to do. Does she defy Papal edict that forbids Jews from rendering medical treatment to Gentiles? Or does she try to alleviate the suffering of this unknown woman, and in so doing, earn the money to pay her husband’s ransom? These are the questions raised by “The Midwife of Venice,” the first novel by former lawyer Roberta Rich. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough had some questions of her own, and she sat down with author Rich to find out more about birthing practices in the 16th century, the transition from lawyer to novelist and what life was like in the Jewish ghetto of Venice.

What was the inspiration for this novel?

I have a very visual imagination. When I was in the museum in the Venetian Ghetto, I saw two things which ignited some images. The first was a shadai, or good luck amulet. I thought of the high infant mortality rate in those times, not just in the ghetto, of course, but all over 16th century Europe and had the idea for a shadai in the shape of a baby’s hand to hang over the cribs for protection. I also saw a pair of silver spoons resting in the glass display case. These crossed spoons became the inspiration for my heroine midwife to design forceps.

How did you conduct your research for it?

Fortunately, I love to read and do research although I must confess I am not a student of history and never took a history course beyond high school. However, there are a number of fascinating books written about Venice and the history of the Venetian ghetto. I was interested to learn that the ghetto was not only a place to sequester Jews, but it was also a relatively safe haven. In a scene from The Midwife of Venice, Hannah and her sister, Jessica, who has converted to Christianity and becomes a courtesan, accuses Hannah of being a ‘little ghetto mouse’, afraid of life. Hannah responds that the same gates that keep them in the ghetto, keep them safe. In fact, the Venetian government, the Council of Ten was protective of the Jews, valued them for their mercantile connections to the Levant (the Middle East) and for the high taxes and levies they were forced to pay for the ‘privilege’ of living in the ghetto.

- No Comments

January 12, 2012 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

A Conversation With Jane Lazarre

In the summer of 2009, Lilith excerpted a section of Jane Lazarre’s harrowing novel, Inheritance. The book was recently published and Lilith’s Fiction Editor, Yona Zeldis McDonough, interviewed Lazarre–author of ten books and creator of the undergraduate writing program at Eugene Lang College at the New School—about historical fiction, blacks and Jews, and her feelings about our first mixed-race president.

In the summer of 2009, Lilith excerpted a section of Jane Lazarre’s harrowing novel, Inheritance. The book was recently published and Lilith’s Fiction Editor, Yona Zeldis McDonough, interviewed Lazarre–author of ten books and creator of the undergraduate writing program at Eugene Lang College at the New School—about historical fiction, blacks and Jews, and her feelings about our first mixed-race president.

Your work is full of interracial relationships; what drew you to this subject?

The first reason is that in my early twenties, I married into an African American family, and in 1969, I gave birth to my first son, a few years later to my second son. Raising Black children, and learning about this nation’s history from the point of view of Black people in my family – a very different perspective than the one I was raised with, that most white people were/are raised with – was a transformational experience.

The theme of race, though secondary, is a central one in my first memoir, The Mother Knot, written in the midst of the feminist movement in the 70s, a movement that was beginning to produce a wealth of material and testimonials, both scholarly and literary, about race history, and by both African American and white writers. Soon after that, as a professor of writing and literature, first at City College in New York, then on the full-time faculty of Eugene Lang College at the New School, I had the opportunity to study and teach African American literature, with special attention to the rich tradition in autobiography. These years of study and teaching had a huge impact on me, on my sense of my own identity as an American, as a white Jewish mother of Black sons, I told some of this story autobiographically in a memoir called Beyond the Whiteness of Whiteness. But apart from the personal sources of my work, I am committed, as a writer and activist-teacher, to speak out against some of the mythologies, indeed, the lies and self-deceptions, of American race history and American racism. The theme of mixed racial identities, about which there is plenty of personal and philosophical disagreement, is also one that has been distorted and misrepresented in many ways since the early days of slavery and up to the present moment – in some of the ways, for example, in which we discuss, define and interpret the history and policies of President Obama.

- 3 Comments

October 27, 2011 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

A Conversation With Nancy K. Miller

Nancy Miller never meant to become a detective. But the distinguished professor of English literature of English and comparative literature at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and the author of more than a dozen books found herself intrigued by the discovery of a small family archive after her father’s death. A handful of photographs, a land deed, a postcard from Argentina, unidentified locks of hair…What had these things meant to her father? And what did they mean to her? So Miller embarked upon a quest: for people, for places, for meaning. The result, “What They Saved: Pieces of a Jewish Past,” was just published by the University of Nebraska Press. In the interview below, Miller talks with Lilith’s Fiction Editor, Yona Zeldis McDonough, about her new book.

Nancy Miller never meant to become a detective. But the distinguished professor of English literature of English and comparative literature at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and the author of more than a dozen books found herself intrigued by the discovery of a small family archive after her father’s death. A handful of photographs, a land deed, a postcard from Argentina, unidentified locks of hair…What had these things meant to her father? And what did they mean to her? So Miller embarked upon a quest: for people, for places, for meaning. The result, “What They Saved: Pieces of a Jewish Past,” was just published by the University of Nebraska Press. In the interview below, Miller talks with Lilith’s Fiction Editor, Yona Zeldis McDonough, about her new book.

What prompted you to write a book about your ancestral objects? Lots of us have things of this kind but wouldn’t have thought to write about them.

I probably would never have undertaken the research for this book, let alone written it, if I had not received a phone call in the summer of 2000 from a real estate agent in Los Angeles telling me that I had inherited property in Israel from my paternal grandparents—and that he could sell it for me. Not just for me, but all the heirs, which meant my sister and my first cousin (whom I had never met), if he was still alive. I succeeded in locating my cousin in Tennessee. His daughter had begun doing research on the family and had found a website already in place for all the immigrants to America with our family name: Kipnis. I had been resigned to not knowing anything about my father’s side of the family. And suddenly, one discovery led to another and I got caught up in the fascination of the quest to find out everything I could about these mysterious relatives and what had happened to them.

- No Comments

May 31, 2011 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Caroline Leavitt on "Pictures of You"

Caroline Leavitt’s new novel—her ninth—starts off with a bang. Literally. Isabelle Stein is fleeing her Cape Cod home and husband after learning that not only has been cheating on her for the last five years, he’s about to father a child with his lover. Stricken and grieving, Isabelle piles her clothes and cameras—she’s a photographer, an identity that is central to the story—into her car and takes off. The day is foggy and even though she is driving well below the speed limit, her visibility is seriously impaired. Suddenly, through the fog she spies a car, facing the wrong way and stopped in the road. In front of the car stands a blonde woman in a red dress. Isabelle feels herself losing control of her car and as she does, she notices there is someone else there too—a boy—who sprints to safety. But the woman remains where she is despite Isabelle’s panicked shouting. Isabelle gets closer and closer; there’s no room to swerve, and she cannot stop. And then, “…the two cars slam together like a kiss.”

Caroline Leavitt’s new novel—her ninth—starts off with a bang. Literally. Isabelle Stein is fleeing her Cape Cod home and husband after learning that not only has been cheating on her for the last five years, he’s about to father a child with his lover. Stricken and grieving, Isabelle piles her clothes and cameras—she’s a photographer, an identity that is central to the story—into her car and takes off. The day is foggy and even though she is driving well below the speed limit, her visibility is seriously impaired. Suddenly, through the fog she spies a car, facing the wrong way and stopped in the road. In front of the car stands a blonde woman in a red dress. Isabelle feels herself losing control of her car and as she does, she notices there is someone else there too—a boy—who sprints to safety. But the woman remains where she is despite Isabelle’s panicked shouting. Isabelle gets closer and closer; there’s no room to swerve, and she cannot stop. And then, “…the two cars slam together like a kiss.”

“So begins “Pictures of You,” a powerful novel about love, responsibility, sin and atonement. In graceful, measured prose, Leavitt not only limns the outer lives of her characters, but delves deep into their hearts as well. What are some of the repercussions of this life altering—and in one case, life ending—collision? Lilith’s Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough asked Leavitt about this and other topics; their conversation is below.

“Pictures of You” deals with issues of moral responsibility, guilt and expiation. As you shaped and wrote the book, did these issues occur to you within a religious or spiritual framework? If so, can you elaborate?

They did occur to me in a spiritual way. I am a big believer in karma. I believe that there are forces in the universe that work with us or against us, and that really, we do reap what we put out there. I loved the idea of Sam [the boy Isabelle saw in the road] thinking Isabelle was an angel, and in a real sense, she was to him. She saves his life in so many ways, and perhaps that goes to the idea that people really can be angels, here on earth.

We know Isabelle was driving the car that killed April, so she is literally guilty, even though it was not her fault. But is she guilty in some more profound sense? Do you believe that she can—or did—atone for her crime?

I don’t really think she was guilty in that there was fog, and she did try to stop the car. But her guilt as in the sense of not taking advantage of all the gifts she had. She stayed in a town she hated. She stayed in a dead-end job. She wasn’t really running to something, which she should have done, as much as she is running away from her life. I don’t want to give away plot, but let’s just say she does atone for those things. What I can talk about is that as she cares for Sam, whom I believe she loves more than Charlie [Sam’s father and the widowed husband of April]–and she certainly does love Charlie–she cares for herself in some way. She opens up the world for Sam with photography, but she also opens up her own world by beginning to see the possibilities and the things that she can do.

Why did you wait to reveal that Isabelle was Jewish? What meaning does that have in terms of her character and the story as a whole?

I’m really spiritual and I love the idea of people coming to belief in their own way. I loved the story of Isabelle’s mother who in her time of grief became a born again Christian and loved the one man she felt would not die or leave her–Jesus. Isabelle is Jewish because Jewish people are often very introspective and they often feel guilty for all sorts of things–at least, that was the way it was in my family. Guilt plays such a large part in my novel, that it meant sense to me that Isabelle would be Jewish. I also, quite frankly, wanted to write about someone who felt like me about these matters, and that meant that I would have to make her Jewish.

What meaning, if any, did her mother’s conversion have for her? Did she embrace a new faith along with her mother or did she retain a sense of her Jewish identity?

Isabelle remained Jewish. She could understand why her mother wanted to be Christian (Jesus would never leave her or die on her), and although she likes the St. Christopher medal, it has nothing to do with belief for her. It is more something that can tie her to her mother. I don’t think Isabelle will ever give up her Jewish identity. It’s simply who she is.

A good portion of the book is taken up with the idea of angels—how they function, what they can—and cannot—do, what role they play in the lives of humans. Did you do much research about this? Did what you read or learned correspond with Jewish thinking and teaching on the subject? What is your own view about angels?

I did do research, which I found to be fascinating. When I discovered that the Hebrew word for angel is messenger, a chill ran through me. It fit perfectly! I even have Sam looking that up and seeing the definition. Sam believes Isabelle is an angel, who can get a message to his dead mother. I also loved that “angels give God distance.” That fit in perfectly with my whole theme of the yearning to connect, and never really knowing the ones we love, which in this case, includes God, doesn’t it? I do believe in God and I’m not sure about angels. However, I have an open mind. The more I read about quantum physics, actually, the more sure I am that anything is possible. Most physicists say that the universe is more incredible and far stranger than what we can imagine, and I love that.

- No Comments

May 16, 2011 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Jennifer Gilmore on "Something Red"

It’s the summer of 1979 and Sharon Goldstein, a professional caterer, is in her Washington, DC kitchen making dinner for her extended family. Her eldest child—Ben—is about to leave for his freshman year at Brandeis and his departure will no doubt reshape and reconfigure this family group. Sharon feels a mixture of excitement, nervousness and sorrow as she contemplates her son’s imminent departure. She takes great care in preparing the meal, thinking, “…it would be perfect to have the family sitting together in the backyard, all along the large communal table, the scuffed wood illuminated by lit candles and flickering torches, before Ben became a dot on the horizon and left the all behind.”

It’s the summer of 1979 and Sharon Goldstein, a professional caterer, is in her Washington, DC kitchen making dinner for her extended family. Her eldest child—Ben—is about to leave for his freshman year at Brandeis and his departure will no doubt reshape and reconfigure this family group. Sharon feels a mixture of excitement, nervousness and sorrow as she contemplates her son’s imminent departure. She takes great care in preparing the meal, thinking, “…it would be perfect to have the family sitting together in the backyard, all along the large communal table, the scuffed wood illuminated by lit candles and flickering torches, before Ben became a dot on the horizon and left the all behind.”

So begins Jennifer Gilmore’s second novel, Something Red (Scribner, $25), a provocative blending of the personal and the political. Lilith’s Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough interviewed Gilmore to get her take on, among other topics, life in the late 1970s, political ideologies as seen through the lens of character, Jews and food, Jews and weight and the execution of the Rosenbergs. Their conversation is below:

What drew you to the time period 1979-1980? Why did it feel essential to set the story at this particular moment? What is your own connection to that time?

A lot of people have asked me why I chose 1979, as I was alive, but quite young. There were lots of reasons I was drawn to it. I wanted to carry on the story of Jewish immigrants in this country (my last novel ends in the sixties), and what life was like for the subsequent generations whose issues were quite different than their parents and grandparents who came here. I was also very interested in the era for thematic reasons. It was the first time one country used food to starve another and I wanted to write about the way food played out in the family and then the way it played out it in the world. My father is an economist and foreign food policy was talked about a lot in our home–mostly at the dinner table–and the conflation of the personal and political struck me even then, though I wouldn’t have described it that way at the time.

And though it was a year I was too young to remember clearly, it was a seminal moment in history, fraught with endless fictional possibilities. Jimmy Carter was in the White House, the Iranian hostage crisis was in full bloom, there had been a nuclear accident at Three Mile Island. Disco was dying, (everyone but my grandfather was happy about this) and so was punk rock in its hardcore form, culminating with the death of Sid Vicious. Women’s oppression seemed to be waning, made concrete by Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party,” shown that year at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Culturally, the world was thriving: Styron’s Sophie’s Choice and Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song were released in 1979. So was Manhattan, The Rose, Apocalypse Now and Breaking Away. Then, on Christmas Day, Soviet deployment of its army into Afghanistan began. And on January 4, 1980, Carter announced the US grain embargo against the Soviet Union, which figures prominently in the book, and is when the novel begins.

Can you talk about the role of research in the writing of this novel? How you did it, and more importantly, how you kept it from showing? (more…)

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...