Author Archives: Susan Weidman Schneider

January 22, 2015 by Susan Weidman Schneider

A Modest Proposal: Create a Fertility Fund

This has been an extraordinary season of news on every front, including (but not limited to) several stories that have had particular resonance for women and for media. Among them: Rolling Stone magazine’s much-discussed coverage of campus rape, followed by an ugly round of victim-bashing after parts of the story were challenged; the resignation of almost the entire staff of the 100-year-old New Republic magazine and the subsequent round of discussions on how a venerable print brand can keep its balance in the roiling mix of digital media sources, and the fact that for many people younger than 100 social media feeds have become their most consistent news feeds as well.

This has been an extraordinary season of news on every front, including (but not limited to) several stories that have had particular resonance for women and for media. Among them: Rolling Stone magazine’s much-discussed coverage of campus rape, followed by an ugly round of victim-bashing after parts of the story were challenged; the resignation of almost the entire staff of the 100-year-old New Republic magazine and the subsequent round of discussions on how a venerable print brand can keep its balance in the roiling mix of digital media sources, and the fact that for many people younger than 100 social media feeds have become their most consistent news feeds as well.

The impact of stories like these loom large for Lilith readers, and some are unprecedented in content and scale. Our national conversation about race, the Barry Freundel mikveh scandal, and the rise of women politicians in Israel and the U.S. as preface to the next round of elections are just three of them. All are subjects Lilith has covered, in print and on the Lilith Blog—and we will continue to write about them with this magazine’s characteristic nuance.

Lilith magazine launched in 1976 with two founding missions: to use the power of independent media to gain greater access for women (and greater value for women’s concerns) in the Jewish world, and to speak with a Jewish voice on urgent women’s issues. I think Lilith’s tagline says a lot about our approach. “Independent, Jewish and frankly feminist,” Lilith charts Jewish women’s lives with exuberance, rigor, affection, subversion and style.

- 3 Comments

October 21, 2014 by Susan Weidman Schneider

The Barry Freundel Case 101

http://www.flickr.com/fmmr

By now we all think we know most of the story.

Rabbi Barry Freundel, longtime spiritual leader of the Modern Orthodox synagogue Kesher Israel in Washington, D.C., has been arrested on charges of voyeurism for having spied upon—and recorded—women undressing and dressing at the mikvah next door to the shul.

Some of the women were preparing to immerse in the ritual bath to mark the end of their menstrual cycle, some as part of the final step in conversion to Judaism, some for reasons of their own accounting perhaps. For all who have used that mikvah in recent months, there’s uneasiness about whose images are on the recording device that Freundel secreted in a digital clock in a mikvah dressing room. But the anxiety—and anger—spread well beyond those who might have been affected directly by the sordid crime of which Freundel is accused.

In brief, and not ranked in order of heinousness, are some of the themes drawn into the web of violations this particular accusation of spying on naked women entails.

- No Comments

October 15, 2014 by Susan Weidman Schneider

Our Seemingly Micro Tzedakah Decisions Can Power Larger Waves

Reprinted from the Fall 2014 issue’s Letter from the Editor

Maybe you’re like me and you’ve tended to see economic justice in terms of fair labor practices, access to good health care, fresh produce in urban food deserts, affordable housing. Big goals with big consequences. Beyond carrying bills in a pocket to give tzedakah graciously or nervously on the street, what small (or larger) potential acts of the pocketbook have escaped our notice?

Maybe you’re like me and you’ve tended to see economic justice in terms of fair labor practices, access to good health care, fresh produce in urban food deserts, affordable housing. Big goals with big consequences. Beyond carrying bills in a pocket to give tzedakah graciously or nervously on the street, what small (or larger) potential acts of the pocketbook have escaped our notice?

Well, you’ve heard the chatter about doing good while buying more stuff. The manufacturer who promises to give a new pair of shoes to a poor child for every pair of its brand you purchase. The company that pledges to donate to breast cancer research an undisclosed portion of its profits from the pink item you’ve just acquired.

Like the rest of us, I figure that I make choices every day—every waking hour, practically—that reflect my values. A lot of these choices are made reflexively, because I’ve practiced them so many times that they’re inadvertent habits. The food I eat—or avoid. Whether I run the water while brushing my teeth or turn off the tap. Which charity solicitations I open and consider vs. which ones I put immediately into the recycling bin. You too?

But there’s another order of choices that feel new to me, a fresh kind of economic consciousness I’ve been thinking about thanks to two women whose actions are worth emulating—and expanding on. These two rabbis have recently been modeling, through their own actions, a different tzedakah. They’re good at remembering that tzedakah comes not out of the idea of charity—giving alms to the poor—but from the root tzedek, righteousness.

- No Comments

October 8, 2013 by Susan Weidman Schneider

When You Can’t Afford a Diaper…

Joanne Samuel Goldblum, photographed by Gale Zucker

During this government shutdown, there are now insurmountable obstacles to accessing many of the vital human services that so many depend upon–food aid to women, infants and children (WIC), for example. The shutdown is not just a matter of government employees losing wages hour by hour (bad enough) but of the grievous plight of people–largely women, in fact–whose very food for survival is in jeopardy. And these benefits at their best are too often insufficient for the people who need them most. Here is one woman who has for 10 years taken on an often unrecognized–but enormous–expense for families today.

“Once you start noticing, the need is everywhere.” So says Joanne Samuel Goldblum, founder and president of The National Diaper Bank Network (diaperbanknetwork.org), the largest diaper bank organization in the nation. She created this innovative nonprofit in New Haven, CT, 10 years ago. This year, through the National Diaper Bank Network, she distributed more than 15 million free diapers to needy families across the country through a network of local diaper banks. According to the organization’s website, nearly 30 percent of low-income families cannot afford diapers.

Honored widely for her pioneering work, Goldblum told Lilith that her early experiences as a social worker, seeing a need that is often quite invisible, moved her to relieve the pain of babies and children who have to spend all day in a urine-soaked diaper — and the shame and depression their mothers suffer (yes, most often the mothers) when they have to put a kid to bed in a dirty diaper because they can’t afford clean ones. Or can’t go to work because they don’t have the money for the diapers you need to send to daycare. “And you are not allowed to pay for diapers on food stamps!” said Goldblum.

“With diapers, once you see the need you start to see it everywhere — towels, shampoo, soap, toilet paper. When you start to think about what happens to families when you cannot afford these things… oral hygiene problems because they don’t have toothpaste or kids going to school dirty because there is no laundry detergent….

“We are taking about diapers, but the bigger picture we are talking about is poverty, and about kids in America — and we manage to ignore this to a large degree.”

Goldblum says her mother, Ellen Samuel Luger, a social worker active in reproductive rights, is her model for activism. “It’s striking to me how many social workers are Jewish women! This fits incredibly well with what you learn as a Jew about social justice. Tikkun Olam is what the rabbi talked about” in the New Jersey Reform congregation where she grew up.

So why are “churches” and not “synagogues” mentioned on The Diaper Bank Network’s website? Although there are synagogues and temples that run diaper drives, Goldblum said, “I have had less luck getting in to speak at synagogues than at churches. It likely has more to do with the ways churches and synagogues do community outreach. We certainly get a lot of support from people affiliated with synagogues. The Diaper Bank Network has been trying really hard to find ways to connect with organizations like JCCs and early childhood programs.” Not surprisingly, Goldblum notes that the biggest category of individual supporters is “young parents — and grandparents.”

One of the seemingly simple policy changes Goldblum advocates is for social-service agencies to have a line item for diapers, which they give out frequently. “They only call them ‘incidentals’ in their budget, though they do spend money on these things. It’s important to name them, so people notice them.”

- No Comments

July 31, 2013 by Susan Weidman Schneider

How do we measure change?

Read Susan Weidman Schneider’s editorial, and so much more, in Lilith’s summer 2013 issue!

Read Susan Weidman Schneider’s editorial, and so much more, in Lilith’s summer 2013 issue!

Maybe you smoked cigarettes a long time ago. Now? Not so likely. Smoking looks retrograde even in an anachronistic setting like TV’s Mad Men. As the smoking seems retro, so too do the sexist attitudes and sexual harassment of that earlier era. Attitudes change, laws then follow suit. (No smoking in theaters or planes, in restaurants or in many public parks.)

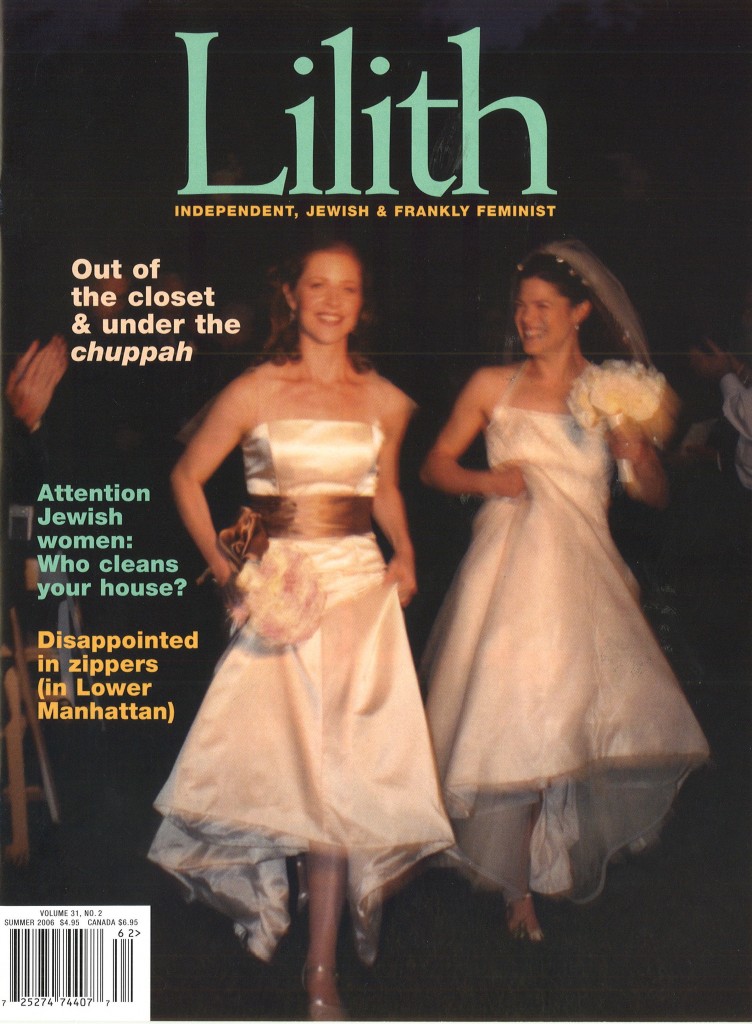

And the Supreme Court of the United States has recognized gay marriage, overturning unjust laws that violated the civil rights of same-sex spouses. The rapid change in attitudes about LGBT issues has been remarkable. From the overt opprobrium during the 1980s AIDS epidemic to social and legal acceptance today? Less than 30 years, and a sea change.

Let’s hope that very soon the attitudes toward women in Jewish divorce law will seem at least as retro as smoking, and that legal succor will follow. As with marriage equality in secular law, attitudes have to shift for new interpretations of Jewish law to take hold. June 2013 was quite a month for attempting such change: women by the hundreds wore tallitot and prayed out loud at the Western Wall in Jerusalem; a “summit” discussed radical ways of countering divorce injustice; and whole new category of Jewish female clergy emerged.

So why can’t we cheer for these successes, however modest they may seem to some? Perhaps because we’re a little skeptical. In the wake of an Agunah Summit in late June, we’ve done an in-office retrospective on our previous articles about Jewish women “chained” in their marriages. Under Jewish law, only the husband can instigate divorce proceedings. From this inequity springs the fact that many husbands extort money or child-custody concessions from their wives in exchange for authorizing the divorce. Blu Greenberg, a prime mover behind the summit and a Lilith contributing editor, first wrote about this subject for the magazine in 1976! (Track this coverage at Lilith.org, part of the stunning archive of back issues fully searchable at our new website.) Blu’s oft-cited statement on how to change Jewish law: “Where there’s a rabbinic will, there’s a halakhic way.” Yet four decades of activism have until now yielded little to free a woman powerless to extricate herself from a bad marriage.

- No Comments

February 27, 2013 by Susan Weidman Schneider

Can You Make a Marriage More Equal?

Did you see MAKERS on PBS, with those many Jewish women trailblazers–like Sheryl Sandberg, Tiffany Shlain, Marissa Mayer (and many Lilith authors)?

Alix Kates Shulman talked about her classic “Marriage Agreement.” It still jolts people after all these years!

Shulman’s iconic, and iconoclastic, argument — that a woman and man should share equally the responsibility for their household and children — was derided when it first appeared in 1970. Norman Mailer, Russell Baker and Joan Didion were shocked, affronted. The real shock is just how resonant Shulman’s take on family politics still is today.

Check out the Marriage Agreement, which we reprised in Lilith’s Summer 2012 issue, along with a new ritual for egalitarian marriage in the 21st century.

Judge for yourself how much progress women have made.

- 1 Comment

December 5, 2012 by Susan Weidman Schneider

When Our Shoes Hobble Our Freedoms

http://www.flickr.com/uggboy

Tell me what it is about shoes this season.

The photographs I see in the glossy ads actually scare me — 19-inch heels on 5-inch platforms. (I exaggerate only slightly.) The shoes on women’s feet would be cartoonish — if only they were in a comic strip.

Look, shoes have meaning. Just check out all the recent books about footwear and websites like Shoe Hero. We know about foot binding. About the iron shoes along a Danube promenade as a memorial to the Hungarian Jews forced to remove their footwear before being shot. About traditional Judaism’s halitza ceremony, in which a childless widow throws a specially designated “halitza sandal” at her unmarried brother-in-law, thus releasing him from his obligation to marry her and continue his brother’s line.

- No Comments

June 25, 2012 by Susan Weidman Schneider

A Journalistic Room Of One’s Own

Cross-posted with The New York Jewish Week.

Thirty-five years of ‘amplifying women’s voices.’ An interview with longtime Lilith editor in chief, Susan Weidman Schneider.

Thirty-five years of ‘amplifying women’s voices.’ An interview with longtime Lilith editor in chief, Susan Weidman Schneider.

In a feat of journalistic longevity, Lilith: The Jewish Women’s Magazine, has been around for 35 years now. Along the way, the quarterly has sought to merge the wider women’s movement with the world of Jewish feminism. On the occasion of its 35 anniversary, The Jewish Week asked Lilith founding editor Susan Weidman Schneider to reflect on the issues that have animated the magazine’s coverage.

The Jewish Week: The early days of Lilith must have really been heady, as you were trying to take the lessons of the wider feminist movement and translate it into the Jewish realm. What was it like starting out?

Susan Weidman Schneider: It’s still heady! Our daily conversations with our interns and writers and editors over lunch at Lilith’s conference table and at Lilith salons are all about taking gender justice, in all its forms, into the Jewish world. Lilith’s tagline says this explicitly: “independent, Jewish & frankly feminist.”

In the beginning we were asked persistently, “Is feminism good for the Jews?” The answer now seems self-evident. Women have energized Jewish life and practice everywhere, from big organizations to the more intimate settings of our own families. Let’s take text as one example. For decades, women in mainstream congregations, small havurot, on college campuses, and in their own kitchens have been writing new liturgies, referring to the feminine aspects of God, and using imagery from women’s bodies and experiences; many of these are now published between hard covers in widely used prayer books; women have expanded the possibilities of prayer and ritual, highlighting the elasticity of Judaism.

- No Comments

October 3, 2011 by Susan Weidman Schneider

Are Jewish Sororities an Untapped Opportunity?

Cross-posted with eJewish Philanthropy.

I’ve been revisiting a 1997 article in Lilith entitled “Jewish Latency,” featured on the cover as “The Jews We Lose.” It’s all about a project Lilith created with the help of a grant from New York UJA-Federation to engage New York Jews in their 20s, just out of college, who found no niche in the Jewish world after having felt very empowered in their campus years.

I’ve been revisiting a 1997 article in Lilith entitled “Jewish Latency,” featured on the cover as “The Jews We Lose.” It’s all about a project Lilith created with the help of a grant from New York UJA-Federation to engage New York Jews in their 20s, just out of college, who found no niche in the Jewish world after having felt very empowered in their campus years.

David Cygielman, CEO of Moishe House, writing in eJP earlier this month declared that the Jewish community too often thinks of people this age as tools for solving “problems” in Jewish life; he noted that this approach “places young adults as unknowing subjects in an experiment they never signed up for.”

But ownership is the key to engaging this cohort, concluded that Lilith article.

The project the “Jewish Latency” article described started out as an idea germinated by Lilith interns, who’d been rebuffed when they approached several Manhattan synagogues wanting seats for the High Holy Days. (This was in an era predating the wonderful services offered by Rabbi Judith Hauptman and others expressly for Jews in their 20s and 30s.) Under Lilith’s mentoring, our interns and their friends decided to create their own Jewish experiences.

Themsleves just out of college, this cohort realized that in addition to finding again the kinds of Jewish leadership opportunities they’d had on campus, they wanted autonomy and agency. They wanted to own what they were willing to invest themselves in creating. The Lilith staff suggested catered Shabbat dinners. Unh unh. Instead, they did DIY potluck vegetarian. We suggested Passover programming. Instead, they hosted a baked-potato third-night seder, announcing that baked potatoes met everyone’s standards of observance. We suggested that the project be called VOICES, an acronym for I-can’t-even-remember-what. The participants renamed themselves “A Tribe Called Jews.” You get the idea.

A Tribe Called Jews came to my mind again this month as I was editing an article on Jewish sororities for Lilith’s fall issue. Lilith is now marking its 35th anniversary, and despite the huge range of subjects the magazine has covered, we’ve never before reported on Jewish women in the Greek system. It turns out that like those Jewish activists – male and female – who germinated A Tribe Called Jews, many young Jewish women in sororities feel empowered in their campus roles, then feel they’ve fallen off the Jewish map after they graduate.

The author of the forthcoming article, Shira Kohn of the Jewish Theological Seminary, spent a decade and a Ph.D. dissertation exploring what goes on in Jewish sororities. She suggests that the organized Jewish community is missing an opportunity to keep these women connected once their college years are behind them. (Here’s an advance look at the article)

Some of Kohn’s insights took me by surprise. Much of what I perceive about sororities is derived from their less-than-flattering images in popular culture. In some circles, every Jewish sorority woman falls under the shadow of the dreadful, evergreen JAP stereotype, as we discovered when Lilith ran a brief report on a newer iteration of this slur – the phenomenon of “Coasties.”

In reality, many sorority members carry out a range of Jewish social-service projects which Kohn’s duly notes. Their campus experiences – for some, a crash course in competency and community leadership – prepare them to assume roles in the wider Jewish world once they’re living out in that universe. But is anyone recruiting these young educated women? Are Jewish women’s organizations and Jewish social justice organizations flooding campuses with suggestions as to how they can stay connected and engaged after graduation? Hardly at all.

- No Comments

August 8, 2011 by Susan Weidman Schneider

Women Are Not Part of the Intergenerational Schism in Jewish Life

Cross-posted with eJewish Philanthropy.

eJP has reported several times on the conflicts between emerging/ startup organizations/ courting the young vs Boomers/established brands/”legacy” organizations. Here’s other news: this tension does NOT come to the fore in the world of women. Women’s legacy organizations have often been funders of, supporters of, and horn-tooters for projects initiated by younger women activists.

eJP has reported several times on the conflicts between emerging/ startup organizations/ courting the young vs Boomers/established brands/”legacy” organizations. Here’s other news: this tension does NOT come to the fore in the world of women. Women’s legacy organizations have often been funders of, supporters of, and horn-tooters for projects initiated by younger women activists.

I’ve been thinking about this as Lilith has been welcoming, enjoying – and benefiting from – our three extraordinary summer interns, who join a distinguished roster of 150 or so previous interns we’ve selected over the years. Lilith has been a kind of graduate program (underfunded, but still…) for young Jewish feminists, almost all of whom have gone on to do wonderful, innovative work in Jewish communities, and in journalism, around the globe. These young women have been nurtured, heard, and taken seriously around our conference table.

Many aspects of the new summer issue of Lilith reflect intergenerational connection, rather than conflict. The cover story focuses on young female athletes mentored by slightly older teammates. Other reports in this Lilith issue similarly reveal the power of intergenerational ties among women, even if those connections weren’t always immediately apparent.

Martin Buber once famously declared “all journeys have secret destinations of which the traveler is unaware.” One of the objectives of feminism is to cultivate a heightened awareness of where we’re headed – a raised consciousness about those destinations, even if the path’s map reveals itself after we’ve arrived.

How do we connect our own stories about life’s journeys – those revealing, shaping anecdotes, often told with studied casualness, about how we left our parents’ home, or ended up in the job we have now, or chose the partner we did – with the larger universe? One of the first tenets of the Women’s Liberation Movements was that the personal is the political. Every day, feminism teaches the alert among us that our quotidian choices have implications beyond ourselves.

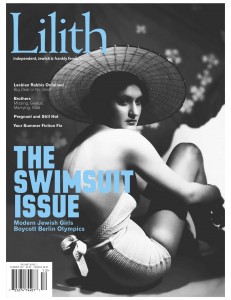

This July, in Vienna, the Maccabiah Games were held for the first time in a European country that was once a Nazi stronghold. The particular pulses outward, implicating the general, with seemingly small episodes offering us larger observations. The Games gave us a chance to remember the connections among Jewish girl swimmers, some in their early teens, who became role models and role breakers in Vienna in the 1930s. They banded together and made excruciatingly difficult personal choices – including boycotting the 1936 Olympics in Hitler’s Berlin. Their star quality and their athletic prowess enabled them to escape the Nazis, rescuing their families, too. They couldn’t have known their destinations when they began to train in the Danube, but their courage and interdependency led a way out.

There’s another angle on female bodies in this issue, about women looking consciously sexy while pregnant. This is clearly a privileged preoccupation in an era when so many women, even here in the First World, don’t have access to family planning or prenatal health monitoring. Challenges to abortion rights now even include the criminalization of pregnancy in some states, where miscarriage can be read as murder. Jewish women’s legacy organizations like NCJW and Hadassah, have been outspoken supporters of the right to choose when and if to bear children.

Feminism says it’s time to reassess the judgments we make up and down the age spectrum. In the back-page memoir, a woman scrutinizes her bad behavior as a young mother, and how it feels to be on the grandmother end of things a generation later. A quiet recollection, it delivering a loud message about the ways we can open our eyes to the needs – and hear the unspoken desires – of older women.

And in good news, Amy Stone reports on what led to the ordination of the first lesbian rabbi to be out of the closet for her entire education at the Jewish Theological Seminary. Poignantly, Rabbi Rachel Isaacs chose as her rabbinic mentor Rabbi Carie Carter – a woman who, in order to become a Conservative rabbi, had to keep her sexual identity hidden for years.

The late, great New York senator Bella Abzug once suggested that women carry stickers to affix to nonsexist ads, gender-neutral products and logos of corporations with a significant percentage of women on their boards, in order to affix to each example an announcement that “This Change Is Brought to You by Feminism.” I thought about Bella when New York State passed its groundbreaking legislation this summer ensuring the right of every gay and lesbian person to get married. (See Lilith’s archive of Jewish lesbian weddings.) Feminism built the scaffolding that enabled the changes at the seminary, the changes in the state, and the changes in our personal consciousness that make for tikkun olam, a better world.

The late, great New York senator Bella Abzug once suggested that women carry stickers to affix to nonsexist ads, gender-neutral products and logos of corporations with a significant percentage of women on their boards, in order to affix to each example an announcement that “This Change Is Brought to You by Feminism.” I thought about Bella when New York State passed its groundbreaking legislation this summer ensuring the right of every gay and lesbian person to get married. (See Lilith’s archive of Jewish lesbian weddings.) Feminism built the scaffolding that enabled the changes at the seminary, the changes in the state, and the changes in our personal consciousness that make for tikkun olam, a better world.

- 2 Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...