Author Archives: Elana Sztokman

October 27, 2020 by Elana Sztokman

Amy Coney Barrett and the Women Who Uphold the Patriarchy

As the world watched Amy Coney Barrett on display in the Senate judiciary hearings, I heard the sound of bewilderment erupting in many people’s heads. It’s like the noise that your Waze makes when you make a wrong turn and then she has to adjust her entire plan; it’s that scratchy sound of reconfiguring – like, something here just does not compute.

The disconnect has to do with the realization that Coney Barrett has two conflicting sides to her persona. She is on the one hand a smart, educated, competent career woman, and on the other hand also a voice–and now, a powerful force–for repressive patriarchal ideas.

- No Comments

February 6, 2020 by Elana Sztokman

Why We Started a New Women’s Political Party in Israel

Photo Credit: Efrat Shpruker

Every time I turn on my computer, I remember why I decided to form a women’s political party. Not alone, obviously, but with a diverse and talented group of women. Nevertheless, I am constantly reminded about what brought me here, every time the screen comes to life.

No matter how many ad-blockers I use, the ads are constant: Do I want a hot babe? Or, do I need Viagra? Or maybe I’m in the mood for a Russian bride?

- No Comments

October 10, 2017 by Elana Sztokman

Why Are Women Dropping Out of Synagogue Life?

Photo credit: Sharon Riddick Groppi

One Friday night in an Orthodox synagogue in Jerusalem 10 years ago, a woman was standing in the back of the sanctuary rocking her hips, soothing her fussy baby. A man walked up to her. She thought to herself, maybe he is coming to welcome me. Instead, he leaned into her and said, “If your baby is making noise, you need to leave the sanctuary.” She left – and never went back.

Exchanges like this have taken place in countless congregations around the world. It is one of the myriad of scenes in which women are made to feel unwelcome. The question is, how are women responding?

In researching this article, the women I spoke to all said that synagogue was once important to them, but that now they are without a congregation to call home. They live in Israel, North America and the UK and are between their twenties to their sixties. They are predominantly Orthodox, but not exclusively. They dropped out of synagogue for a variety of reasons, each of which presents its own biting critique of Jewish communal practices.

“The rabbi noticed I wasn’t there,” reports Aviva, a 40-year-old mother of three from the United Kingdom who stopped going to services two years ago. “He said, ‘We missed you’, but never actually asked the question about ‘why’. I was dying for him to ask. But he never did.”

Consider “Nadia” (name changed at her request, as are those of the other women I interviewed). ) On the Friday night that she led the Kabbalat Shabbat services in her “partnership minyan,” (an Orthodox service that separates the sexes but allows women to lead certain parts of the service). She made a one-word change to the song “Lecha Dodi.” Instead of using the word “ba’alah” (literally, “her owner”) to designate “husband,” she used the word “isha” (literally “her man), a word that is used in many feminist spaces in order to avoid the connotation that women are property. As a result of this change to the liturgy, one man in her shul was incensed. He started circulating around the men’s section in fury, trying to rile people up. Unsuccessful, he simply went to the podium and announced, “This woman does not represent the community. We are not Conservative.” Nobody reacted or told him to stop. Nobody said that it wasn’t his place or his role to speak on behalf of “The Community.” And not one person in the synagogue approached Nadia to apologize for her being humiliated this way. Nadia never returned to the congregation, and nobody seemed to care. The man who humiliated her stayed for many years, and was given many honors. Life went on without her.

These are not stories of cloistered Hassidic women breaking free with great drama. These are educated, modern women who quietly slip away from a communal life in which they feel unwelcome or unwanted. A mid-life rebellion may not even look like one. These quiet, private rebellions—which result from experiences around gender inequality, social isolation, or public shaming—have not evolved into a movement, but they reflect what might be a significant trend in communal life. Tinged with loneliness, frustration, sadness and liberation, their narratives offer a powerful about the tremors beneath the surface of deceptively happy Jewish communities.

- 6 Comments

July 13, 2017 by Elana Sztokman

Stop Asking “Why Are You Still Orthodox?”

Recently, at the #HUC #HealingHatred conference, Shira ben Sasson Furstenburg gave a talk about the connection between religious extremism and sexism. She talked about how pretty much all major religions equate “more religious” with notions of control over women’s bodies. This is an idea that I talk and write about a lot, so I listened intently.

Recently, at the #HUC #HealingHatred conference, Shira ben Sasson Furstenburg gave a talk about the connection between religious extremism and sexism. She talked about how pretty much all major religions equate “more religious” with notions of control over women’s bodies. This is an idea that I talk and write about a lot, so I listened intently.

During the question and answer period, the very first question was addressed at her: Why are you then still Orthodox?

Before she responded, Shira said, “You realize that you are asking a very personal question, even though this panel was not a personal one.” She then proceeded to answer anyway, talking about the importance of fighting for change from “within”—a comment that drew applause.

- No Comments

April 17, 2017 by Elana Sztokman

Jewish Women in India Have a Powerful New Role Model

Simcha Sharona Massil Galsurkar is busy. The 37-year-old mother of three, who works as a full-time Jewish teacher and is one of the pillars of the Mumbai Jewish community, spends every spare second preparing educational materials. A member of India’s 2,000-year-old Bene Israel community, Sharona works on a range of projects, from organizing learning groups to collaborations with local organizations like the JDC and Chabad, to ensuring that her three daughters ––Tiferet,13, Tehilla,11, and Emunah,8 ––don’t miss any aspect of a Jewish upbringing. xe88

Simcha Sharona Massil Galsurkar is busy. The 37-year-old mother of three, who works as a full-time Jewish teacher and is one of the pillars of the Mumbai Jewish community, spends every spare second preparing educational materials. A member of India’s 2,000-year-old Bene Israel community, Sharona works on a range of projects, from organizing learning groups to collaborations with local organizations like the JDC and Chabad, to ensuring that her three daughters ––Tiferet,13, Tehilla,11, and Emunah,8 ––don’t miss any aspect of a Jewish upbringing. xe88

This time of year, though, she is even busier than usual. Like so many Jewish women around the world, she had been getting ready for Passover. But her task is particularly heavy: not only hosting a Seder for 80 to 100 people, but also assigning herself the task of keeping this holiday alive in a community where Jewish connections are fading.

- No Comments

October 14, 2016 by Elana Sztokman

God’s Girlfriends: A Review

http://www.arab-hebrew-theatre.org.il/en/show.php?id=140

I recently investigated the following question: Does the Bible pass the Bechdel test? You know, this is the test about how pro-women a dramatic production is. The test is simple, and sets an admittedly low bar. In order to pass, the film, show, or play has to have at least two named women as characters, and the two have to talk to one another about something other than a man for more than 30 seconds. I was curious how the Bible fares.

The answer? Out of the 24 books of the Bible, only one book passes: The Book of Ruth.

- No Comments

October 11, 2016 by Elana Sztokman

Does Judaism Generate Eating Disorders?

Many women struggling with traumas around food and body shaming have stopped fasting on Yom Kippur. Cognitive behavioral psychologist Aliza Levitt, a specialist in eating disorders, says that for many women food is like a drug. “Like with any other drug, you can’t just take food away. It is a matter of life and death. Eating disorders have a high mortality rate, and you have to take that into account.”

But it’s more than that. The trauma of food triggered by Yom Kippur reflects a deeper problem in Jewish culture when it comes to food. The overemphasis on food in excess in Jewish life—so often served by women—combined with family surroundings in which body commentary is the norm, can launch different painful relationships with food and body.

- No Comments

October 11, 2016 by Elana Sztokman

Choosing Not to Fast: Eating Disorders and Yom Kippur

Last year on the eve of Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, Naomi Malka was busy. The High Holiday Coordinator and Mikveh Director at the Adas Israel Congregation in Washington, DC, she was preparing for a 6PM service for five thousand people and had no time to eat. For most people who observe this holiday – which, according to the Guttman Center, is the majority of Jews – the 25 hour fast is hard enough. But to start the fast already on an empty stomach and to be running around organizing and working, that is bordering on painful. But for Naomi, the challenge was even more extreme: she is also a recovering bulimic.

- 1 Comment

April 13, 2016 by Elana Sztokman

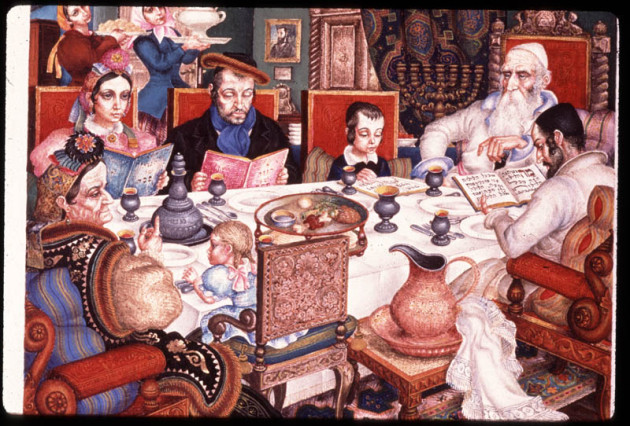

Passover: Freedom for Women NOW—Not 3000 Years Ago

“Passover,” Arthur Szyk, 1948. Yeshiva University Museum.

There is no holiday that brings out the screaming in my head as much as Passover.

There are two sets of noise that take hold of my brain at this time of year: the pre-Pesach (Passover) trauma and the Seder night trauma. Or as I have come to experience it, the trauma created by women’s stuff, and the trauma created by men’s stuff.

Growing up, the pre-Pesach anxiety began as soon as Purim was over. We were only allowed to eat from a pre-determined collection in the kitchen, we were on a schedule around what rooms were already sterilized, and my mother’s mood went from the usual cold and cranky to the downright hostile. Nothing was ever right, we walked on eggshells, and life was insane and frenetic. Although I often wonder how many of my traumas are from religion and how many are from my particular family, in this particular case I have come to learn that this kind of thing was going on not only my own house but also in many Jewish homes around the world. Even women of privilege engage in the panic. (I’ll never forget the time, years ago, when a mother frantically came to pick up her daughter from a play date around a week before Pesach, saying, “Hurry, I have to rush home and watch my cleaning lady do the kitchen.”) Pre-Pesach insanity, it seemed, was the Women’s Way, no matter how you celebrated the holiday.

I’ve been living in Israel for over 20 years, and it is still astounding for me to watch how this culture takes over Jewish women’s lives, no matter what kind of religious observance they adhere to during the year. Conversations in shops, on the street, and online, revolve around Jewish women of all backgrounds managing the minutia of obsessive cleaning, shopping, and cooking. There seems to be an uncontrolled lust for women comparing themselves to one another—who started cleaning and cooking earlier, who is having more guests, who is more efficient, who is more creative, and ironically also who has more time-saving hacks. Facebook doesn’t help, by the way.

Growing up in Orthodox Brooklyn, I found this pre-Pesach cleaning-cooking-hosting-mania was compounded by the other assault on women’s bodies: clothing shopping. Our job, as religious girls, was not only to manage the kitchen, but also to look gorgeous as we did it. We prepared our shul and Seder outfits meticulously and expensively, down to the last perfectly-matching accessory. But let me tell you something: there is nothing quite as dysfunctional within the female experience as surrounding yourself with copious amounts of food and then forbidding yourself from eating it. Women’s and girls’ table conversation, once we finished serving, invariably revolved around calories, points, fat content, carbs, gluten, GI, cellulite, whatever. (Each year, the measures for what we should or shouldn’t eat changed, led by trends announced by The New York Times. This added to women’s competition not only over who was thinnest, but also over who was the most in-the-know about how to effectively lose weight.)

- 2 Comments

May 29, 2015 by Elana Sztokman

Voyeurism and the Yeshiva Girl

Madonna has got me thinking about Barry Freundel. To be honest, Madonna often gets me thinking about body, sexuality, and women’s power. I consider Madonna one of the most body-empowered women out there. She has full command of her body, and uses it as her artistic canvas. She can do anything she wants with it, put on any item of clothing and pose in any position, and the effect is one of power and ownership. I frequently find myself wondering whether she represents an ideal of body empowerment, whether on some level I should be teaching my daughters to admire and emulate her for her complete ownership of her life and seeming ability to do anything she wants. (Of course, then the Orthodox voice in my brain usually kicks in and reminds me of how far Madonna is from anything familiar to me in my own relationships with my body.)

Anyway, knowing this about Madonna, I was surprised to discover a few months ago that she took to twitter to express her anger that a photo of her was leaked without her permission. The photo was an unpolished image of her in bra and underwear, apparently in a dressing room. “This is a fitting photo I did not release,” she wrote. “I am asking my true fans and supporters who respect me as an artist and a human to not get involved with the purchasing trading or posting of unreleased images or music.” The reason I was surprised at her reaction was because the week before, she had done a topless photo shoot for a French magazine. It was a strange juxtaposition to me, that she would upset about this photo of her in her underwear when just days before the entire world just saw her undressed.

- 2 Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...