Author Archives: Aileen Jacobson

April 27, 2018 by Aileen Jacobson

What Is a Feminist Audience to Make of Albee’s Anti-Semitic Matron?

Glenda Jackson in Edward Albee’s Three Tall Women, directed by Joe Mantello, at the Golden Theatre. Photo credit: Brigitte Lacombe.

Edward Albee often said that he modeled the main character in “Three Tall Women” on his adoptive mother, from whom he was estranged and about whom he never had anything good to say.

If it’s a revenge play, as some people have speculated, then he failed, though he presents the old woman with all her failings, including an anti-Semitic (and racist) streak. But the two-act drama now at the Golden Theater on Broadway is far more nuanced than that.

First of all, it is a terrific play and a terrific production, often bitterly funny about the indignities of aging. (I don’t recall laughing much, or hearing much laughter, during its 1994 Off-Broadway debut.)

The play is also, it turns out, far more forgiving and understanding about the flinty, demanding and frequently imperious central character played by Glenda Jackson than the playwright perhaps intended. Or, more likely, he did intend, as he explored the reasons for his mother’s extreme discontent, to come to terms with how she treated him. And to allow audience members to come to their own conclusions.

- No Comments

April 12, 2018 by Aileen Jacobson

How Feminist is the “Mean Girls” Musical, Really?

“Mean Girls” playing at the August Wilson Theater.

“Mean Girls,” the shiny new musical about high school cliques written by Tina Fey and based on her movie of the same name, concludes with some upbeat messages for teenaged girls: Don’t pretend to be less smart than you are to attract boys. Don’t try to be someone you’re not in order to fit in: be yourself. And don’t forget to be, as one anthem is titled, “Fearless.”

Wait a minute! Is this 2018? Why do girls still need to be told these basics? And this is supposedly an updated version of the 2004 movie, not a throwback. There are plenty of references to social media and a new nugget of advice: Don’t send nude photos of yourself over the internet, because boys will share them, though wouldn’t it be nice if they didn’t.

This apparent lack of progress can make a seasoned feminist’s heart sink. Has anything really changed over the last half-century?

The show, with music by Jeff Richmond (Fey’s husband) and lyrics by Nell Benjamin (who co-wrote music and lyrics for the similarly upbeat “Legally Blonde”), is hardly anti-feminist, and it could be seen only as a good-natured and often funny look at an awkward period in everyone’s life. But it sends mixed messages. The most envied girls at the high school wear super-short skirts, super-high heels and manes of glossy hair. These are the title’s mean girls, and who wouldn’t want to be like them? The musical is supposedly saying that no one should—but that is not the aesthetic or emotional message.

- No Comments

December 23, 2017 by Aileen Jacobson

When a Woman Made Decisions at Washington Post: New Movie Tells All. Or Most.

The Post, 20th Century Fox

“The Post,” a new movie starring Meryl Streep and Tom Hanks and directed by Steven Spielberg, could be seen mainly as a saga about the Vietnam-era Pentagon Papers. Or it could be seen as a film about the workings of a newspaper—in this case, The Washington Post.

But, really, what it most feels like is a story about the evolution of a feminist, or at least the beginnings of that evolution. That emerging feminist is Katherine Graham, then the publisher of the Washington Post, a position that had been thrust upon her after her husband’s suicide. She had to make the difficult decision of whether to print contents of the leaked Pentagon Papers despite threats of criminal charges from the White House and warnings from bankers that the move could lead to her company’s demise.

- No Comments

December 7, 2017 by Aileen Jacobson

Your Jewish and Frankly Feminist Review of “The Wolves”

A scene from the Lincoln Center Theater production of “The Wolves.” Photo credit: Julieta Cervantes.

Nine high school girls on a soccer team somewhere in suburban America are discussing, of all things, the Khmer Rouge, during the opening scene of “The Wolves.” This 90-minute wonder of a play is now running at Lincoln Center’s Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater.

One girl admits to never having heard of the Khmer Rouge, a regime that murdered 1.5 to 3 million people before losing power in 1979.

“They’re like Nazis in Cambodia,” answers another.

“But in the 70s,” adds another girl.

“That’s not quite…” chimes a third, before getting cut off, something that happens often as these girls chat without regard for finished sentences or thoughts. Menstrual blood and other topics are interspersed in their conversation, peppered with outbursts like “omigosh” and frequent four-letter words.

The part that stood out for me was that, confused as many of the girls were about world history, they used Nazis as their touchstone for defining evil. No one argued that point.

- No Comments

December 1, 2017 by Aileen Jacobson

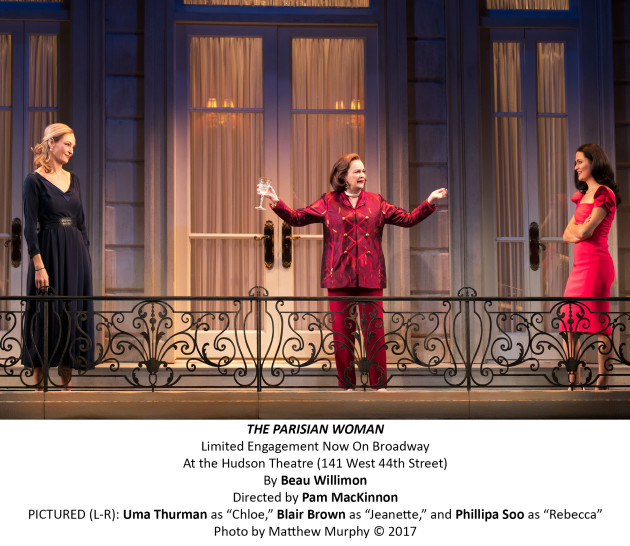

Your Jewish and Frankly Feminist Review of “The Parisian Woman”

A female nominee to chair the Federal Reserve. A male contender for a federal Court of Appeals position. A striving young some-day female president. And, at the center of it all, movie star Uma Thurman making her Broadway debut as Chloe—a conniving political wife doing her utmost to secure a powerful position for her husband.

A female nominee to chair the Federal Reserve. A male contender for a federal Court of Appeals position. A striving young some-day female president. And, at the center of it all, movie star Uma Thurman making her Broadway debut as Chloe—a conniving political wife doing her utmost to secure a powerful position for her husband.

“The Parisian Woman,” a snappy, entertainingly slimy 90-minute comedy that has just opened on Broadway, certainly has many characters and themes for a feminist to ponder. It’s set in Washington, D.C. in the “present”—yes, right in the middle of the ever-evolving Trump presidency.

While it makes no overt references to Jews aspiring to or attaining high office, that doesn’t mean there is nothing for Jewish feminists to gnaw on.

- No Comments

November 13, 2017 by Aileen Jacobson

Your Independent, Jewish and Frankly Feminist Review of “The Band’s Visit”

Kristina Lenk’s right arm floats, gracefully and magically, as she sings about memories, emotions and desires—not that the rest of her body or her lovely voice aren’t just as expressive in “The Band’s Visit,” the new Broadway musical about sweet and bittersweet encounters between Jews and Arabs in a tiny Israeli town.

Kristina Lenk’s right arm floats, gracefully and magically, as she sings about memories, emotions and desires—not that the rest of her body or her lovely voice aren’t just as expressive in “The Band’s Visit,” the new Broadway musical about sweet and bittersweet encounters between Jews and Arabs in a tiny Israeli town.

Her swaying arm, however, seems to embody the complicated make-up of the actor’s character, Dina, a former dancer who, because of a romance gone bad that apparently derailed her career, has learned to “settle in” to a more constricted life as the proprietor of a cafe.

Dina seems to be happy enough, playing a central role in her community, confident, competent and in charge. She organizes her town’s response when an Egyptian band lands there by mistake, resulting in unexpected bonds. In Dina’s case, it also leads to revelations of her yearnings for a less lonely, more connected life. She embodies a dilemma that feminism hasn’t able been to solve: that of a strong woman who has made bold decisions but finds herself regretting some of them and reconciling herself to a life she didn’t choose.

The musical, based on a 2007 Israeli movie with the same title, had a highly praised, award-winning run at the Off-Broadway Atlantic Theater last December and January. Now, less than a year later, it has landed at the much-larger Ethel Barrymore Theater on West 47th Street, with an expanded though similar turntable set and most of the same cast. That includes the two leads, Lenk (who meanwhile took a starring Broadway turn in “Indecent,” about the scandal surrounding a 1920s Yiddish play, which can be seen on PBS’s Great Performances on Nov. 17, and Tony Shalhoub, who plays Tewfiq, the stiffly courteous leader of the hapless but grandly named Alexandria Ceremonial Police Orchestra.

The qualities that helped make the earlier stage production so beloved—the quiet intimacy, fable-like moments, and oblique hints rather than blatant announcements of its theme—remain intact. Could David Cromer’s carefully calibrated direction use more briskness? I don’t think so, though a friend who saw the show for the first time with me thought it could—just a tad. It also makes virtually no mention of the discomfort that Egyptians and Israelis might feel in each other’s presence. But an infusion of global politics would require a wider lens than the one chosen by Itamar Moses, the author of the musical’s book, and David Yazbek, the lyricist and composer who wrote a glorious score that mixes Middle Eastern inflections with pop melodies and more. The show focuses more narrowly on the human interactions, with a wry humor that is also understated.

The tone is set with projections of simple words during the overture: “Once not long ago a group of musicians came to Israel from Egypt.” That is followed by: “You probably didn’t hear about it. It wasn’t very important.”

The first scene, in an airport bus station, establishes how the band comes to visit an isolated town in the Negev desert. They are on their way to perform at the dedication of a new Arab Cultural Center in Petah Tivka (a real city with more than 230,000 inhabitants east of Tel Aviv). But they take a bus to sparsely-populated (fictional) Bet Hatikva, which they pronounce as though it is written Betah Tikva.

Once they arrive, the townspeople—well, Dina and the two guys who seem to hang out at her cafe all day long—set them straight about the vast gulf between p and b. (The Israelis and Arabs speak English to each other, because it’s their only common language, though both groups speak English imperfectly and laboriously, putting an accent on an underlying theme of communicating between cultures.)

As Dina sings in a jaunty song, Petah Tikva is “such a city, everybody loves it, lots of fun, lots of art, lots of culture.” Her town, with the fateful b, is “basically bleak and beige and blah blah blah.” It has no art or culture–and no hotel, either. She suggests (or commands, really) that the seven musicians and their conductor be divided up to board overnight at the cafe, at her place and at the home of the unemployed Itzik (John Cariani, who later sings a delicate lullaby to his infant son).

Dina chooses Tewfiq as one of her boarders, and it’s immediately clear that she finds the band leader attractive, despite his melancholy demeanor. Or perhaps because of it. He seems as alone and unmoored as she does. She shares some of her longings in the song “Omar Sharif,” about watching romantic movies with her mother, one of best songs among many moving melodies. Dina’s “Something Different,” especially as rendered by Lenk and her arm movements, is another standout. Something does indeed bloom between Dina and Tewfiq, though not what you might expect in a musical.

This show stays mercifully free of sentimentality. It does have a streak of old-fashioned sentiment, though, such as a man identified in the program as Telephone Guy (Adam Kantor) who has spent every night for at least a month silently staring at an outdoor public telephone waiting for his girlfriend to call. He’s not as metaphorical as a fiddler on the roof, but he could be one of the inhabitants of Anatevka. Late in the show, he sings a plaintive song, “Answer Me,” which the entire ensemble eventually joins in on.

That thoughtful tone, though, doesn’t mean the show is devoid of bright spots. It has many. For one thing, the band members often play their instruments on stage—very nicely and often rousingly, supplemented occasionally by a few offstage musicians.

At Itzik’s home, Israelis and Egyptians joyously sing a few stanzas of “Summertime” together, reveling in their common knowledge. The song sparks a recollection by Avrum (Andrew Polk), Itzik’s father in law, of how he first saw and fell in love with the woman who would become his wife. He explains the importance of music in the romance (“love starts when the tune is sweet”) in “The Beat of Your Heart,” a snappy ballad with a Latin infusion (“The Girl from Ipanema” is one of the tunes the lyrics refer to).

In another upbeat scene, band member Haled (Ari’el Stachel), a smooth fellow who previously exhibited a mildly creepy side by ineffectually coming on to nearly every woman he sees, redeems himself. In a mellifluous number, “Haled’s Song About Love,” he gently tutors the awkward Papi (Etai Benson) in a roller rink on how to woo his date, Julia (Rachel Prather).

It should be noted that, except for Dina, there are no major roles for women. Itzik’s unhappy wife, Iris (Kristen Sieh), makes an impression with her frustration at having to take care of an infant all day and all night, but that’s a brief sequence.

However, the whole show belongs to Dina. And to Lenk. At the end, she says the words seen at the beginning: “You probably didn’t hear about it. It wasn’t very important.” But it was.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.

- No Comments

July 7, 2017 by Aileen Jacobson

“Marvin’s Room” Explores Sisterhood and Caregiving

Why are women expected to be caregivers—for their children, their parents, and sometimes for other relatives as well—while men are not?

Why are women expected to be caregivers—for their children, their parents, and sometimes for other relatives as well—while men are not?

That is not the question being asked by “Marvin’s Room,” a 1990 play by Scott McPherson now making its Broadway debut in a beautifully calibrated and engrossing production. Nevertheless, the question may occur to women in the audience.

The comedic drama, directed by Anne Kauffman, explores the relationship between two sisters who became estranged some 20 years earlier, when one stayed home to care for their dying father and his ailing sister while the other departed to pursue different paths, eventually becoming a single mother of two boys and a candidate for a degree in cosmetology, which she hopes will lead to a more affluent and fulfilling life. After the caregiver discovers she herself has leukemia, she reaches out to her sister and nephews as possible bone marrow donors, and they come to visit. The story is told with a lot of wry, absurdist humor about such subjects as awkward doctor visits, painful backs and encounters with costumed actors at Disney World.

- No Comments

April 28, 2017 by Aileen Jacobson

Find Out Why “A Doll’s House, Part 2” Surprises Feminist Audiences

Laurie Metcalf in a scene from A DOLL’S HOUSE, PART 2 . Photo credit: Brigitte Lacombe

Who would ever have imagined that a sequel based on any play by Henrik Ibsen could be a nearly nonstop laugh fest? But “A Doll’s House, Part 2,” now playing on Broadway, is just that—and without being disrespectful toward the serious feminist themes in Ibsen’s 1879 drama, a benchmark in its examination of women’s struggles in a male-dominated environment and an affirmation of a woman’s right to go her own way. As Karl Marx said about history, theater sometimes covers the same ground twice, “the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.”

Actually, the new work by Lucas Hnath, a 37-year-old playwright who has written several well-received Off-Broadway plays, doesn’t repeat Ibsen’s plot, though it does revisit the views toward women that Nora Helmer, the play’s heroine, rebelled against when she famously slammed the door on her house, husband and three children, and left to explore the possibilities of an independent life. Now it’s 15 years later, and there’s a knock on the same door Nora had used to escape what would have been her fate of continuing to be treated as a “doll,” cared for and condescended to by a tradition-bound husband. Is she in trouble? Yes, but not in a way you might anticipate.

Nora strides in, beautifully dressed and loudly assertive, a successful and wealthy author of books about “the way the world is towards women and the ways in which the world is wrong,” as she tells Anne Marie, the elderly nanny who stayed with the family to raise her children. One novel is autobiographical and has encouraged other women to leave their husbands, she says. She uses a pseudonym, but an angry husband tracked down her real name, and that has led to her discovery that her husband, Torvald, never divorced her, which she had assumed he had. A revelation that she is still married would brand her as a hypocrite. Worse, it would make her a criminal. She has “signed contracts, done business, had lovers—all sorts of things that a married woman isn’t allowed to do, that are illegal, that amount to fraud.” A divorce would straighten things out. (Illegally signing a document, though for a good reason, got Nora into hot water in Ibsen’s play—but you don’t have to know the original to understand this one.)

My thoughts turned to the Orthodox Jewish stricture through which a woman is not divorced unless her husband gives her a document called a gett. A man gives the gett to the woman. There is no vice versa.

- No Comments

April 13, 2017 by Aileen Jacobson

Powerful Women at War

Patti LuPone in WAR PAINT, photo by Joan Marcus

Toward the end of “War Paint,” the new Broadway musical about two queens of the cosmetics industry, one Jewish and one not, Elizabeth Arden (the blond, blue-eyed Christian one) asks in a lyric whether they had made women more free or helped “enslave them.”

Helena Rubinstein, the makeup mogul with darker hair and a longer nose, who was born in a Polish shtetl, replies, “Perhaps they will forgive us when they look at what we gave them.” That would be more than just lipsticks and creams to make them more alluring and, maybe, establish a clearer sense of self-worth (or maybe make them doubt their worth if they didn’t embellish their looks). The two also demonstrated how far women could go in business, establishing their own highly successful companies and amassing millions of dollars.

- No Comments

April 4, 2017 by Aileen Jacobson

Gender Plays Out on B’way

The theater was packed—there had been long lines outside as invited guests and hopeful members of the public jostled to enter and find seats. Inside, the stage of the August Wilson Theater, which opened in 1925 with a production of George Bernard Shaw’s “Caesar and Cleopatra,” was filled with theater luminaries. It was December 6, 2016, and the 1,200 or so people in attendance were gathered to pay tribute to Edward Albee, who had died two months earlier at the age of 88.

It was a lovely event, filled with anecdotes from colleagues and excerpts from Albee’s plays delivered by well-known actors, and I was happy that a friend had invited me along. It slowly dawned on me, however, that among the dozens of speakers who rotated on and off the stage, there was only one female playwright. That was Emily Mann—and she was introduced not as a playwright but as a director, which was indeed her role in Albee’s life. Everything said on the stage was appropriate for the occasion, including the comments by Terrence McNally, John Guare, Arthur Kopit and Will Eno, all fellow playwrights who, like Albee, have had shows produced on Broadway, the pinnacle of American commercial theater.

But wait, I thought to myself, where are the women?

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...