Author Archives: admin

January 31, 2008 by admin

Having It All, Jerusalem-Style

On Friday morning, I was cooking for Shabbat and cleaning my Jerusalem apartment while listening to a radio station that shall remained unnamed. While I cut up cauliflower, I listened over the airwaves as someone leyned selections from the Torah portion and haftarah. (This is generally good review for my own leyning the next day in shul – except when the radio rabbi leyns in Sephardi trope!) Then, while chopping onions, a new program came on: a d’var Torah about the leadership skills we can learn from Moshe

Rabbeinu in sefer Shmot. This was followed by the 11 o’clock news, which concluded with, “Shabbat begins at 4:32 and ends at 5:49. The times for Shabbat this week are sponsored by Hepi diapers. We remind you that Hepi diapers have special adhesive that can be used on Shabbat. Make your baby a Hepi baby all week long!”

By the time my vegetable kugel was in the oven, it was time for my favorite program: Chidat Haparsha, a trivia question about the weekly Torah portion. The question this week, in honor of the Ten Commandments which were inscribed “from one side and from the other side,” was about a palindromatic word that appeared in the parsha. As soon as the riddle was announced in full, listeners began to call in with answers. It turns out that there are a lot of palindromatic words in this parsha, as I learned, though no one gave an answer that met all the qualifications. I stayed tuned.

I was surprised at what happened next: A woman called in, Shulamit from Be’er Sheva, the first woman I’d ever heard on this program. She answered, “The word is Hineh,” and then proceeded to explain how this word answered each part of the riddle. The radio announcer heard her out, and then asked, “And what is the verse in which this word appears?” Over in Be’er Sheva, Shulamit paused. “I’m in the kitchen,” she said, “I don’t have a Tanach in front of me.” The radio announcer apologized; the answer had to be

accompanied by the full text of the verse. But it seems that woman had made an impact, because the next caller was also a woman – Chedva from Netanya. Chedva gave the same answer as Shulamit, but cited the verse, albeit incorrectly. “I’m sorry,” said the announcer. “That’s not the verse.” She had just one or two words wrong, I noted. Chedva sighed. “I’m also in the kitchen,” she said, and I felt the weight of thousands of years of Jewish women’s kugels bearing down on her shoulders as she sighed and hung up.

Not surprisingly, a man called in next, gave Shulamit’s original answer with the correct text of the verse, and the Hasidic choir on the air broke out in a round of rousing zemirot. And so, as happens each week, a man won Chidat Haparsha, and the radio announcer moved on to the pre-Shabbat traffic report.

I was not planning to travel anywhere that afternoon, so I turned off the radio and went back to my cooking. I have nothing against

women in the kitchen—someone has to cook for Shabbat—but I do wish that more women leyned the parsha. The secret of leyning well is that you really do learn the Torah by heart. This means that you can cite the right answer to Chidat Haparsha even while your hands are stuffing a chicken. Who said women can’t have it all?

–Chavatzelet Herzliya

- 3 Comments

January 30, 2008 by admin

Checking the Boxes

A new collection of Hannah Arendt’s writings on Jewish subjects is about to be published, cleverly titled “The Jewish Writings.” Arendt

wasn’t known primarily as a Jewish writer (even though Eichmann in Jerusalem may be her best known work), but she wrote a lot about Jewish themes and issues, maybe even more than she wrote about anything else. In the current issue of the Boston Review, Vivian Gornick considers this group of Arendt’s articles and essays. It’s an interesting piece overall, but I’m going to skip right to the end. Gornick describes the letter Gershom Scholem wrote to Arendt after the publication of Eichmann in Jerusalem, famously accusing her of having “no love of the Jewish people.”

Here’s Gornick’s assessment of Arendt’s response:

“[B]eing a Jew had been a given of her life. Not only had she never wished to be anything else, but being Jewish had made her appreciate, as nothing else could have, the significance of being allowed to be what one is: ‘There is such a thing as a basic gratitude for everything that is as it is: for what has been given and not made.’

This regard for the givens of individual human existence had led her to think deeply about everything she had thought mattered during the previous thirty years. What she loved was the experience of the Jewish people: it had taught her how to consider the human condition at large. How much more Jewish did she have to be?”

How much, indeed? I came across Gornick’s piece while poking around for stories that dealt in some way with both Judaism and feminism. It’s the “and” where things get tricky. For something to qualify as “Jewish feminist,” do both boxes have to be checked? And how do we go about checking them?

This question is hardly new to readers of Lilith, or to other folks who identify as feminists, Jews or any combination of the two. But it’s one I can’t get away from, and it’s thrown in sharper relief when I’m sifting through other people’s material and trying to figure out what fits. “Jewish feminism,” is seems to me, can be awfully specific.

Identifying whether or not something is feminist has always been easy for me; even if the definition of that word remains in question, my “test” for feminism is basically a version of what the Supreme Court said about obscenity back in 1964: “I know it when I see it” – and just as importantly, when I don’t (though the gray areas are where things get the most interesting, anyway).

Judaism is more specific. There are basically two “tests” to determine whether a book or movie or whatever else is Jewish enough to be discussed in terms of its Jewishness: does it involve or address Jewish ideas? And, is the author Jewish? To get the attention of the Jewish press, the answer to one of these questions generally has to be yes. Of course, it depends who’s doing the answering.

The second question would seem to be the easier one to determine, but really, neither is all that straightforward. There’s a basic way to know whether or not a person is Jewish: is her mother Jewish? But lineage rarely tells the whole story. And when publications like the Jerusalem Post keep score of every Oscar nominee who’s even remotely connected to Judaism (references to Daniel Day Lewis being the son of “British Jewish actress” Jill Balcon particularly smack of desperation), I’m not sure what value the easy definition really has.

Which is not to say I’m in favor of a stricter one, one that would mean the Post ignored actors of Jewish descent unless their

Judaism was, in Arendt’s terms, made as well as given. For the purposes of my nascent blogging here, it can be tricky to avoid using overly simplistic tests when deciding what counts as Jewish feminist arts and culture. It drives me crazy.

–Eryn Loeb

- 1 Comment

January 27, 2008 by admin

Could It Be, Orthodox Women Rabbis? Not Exactly.

There’s been lots of hype surrounding the announcement of the Shalom Hartman Institute’s new ordination program that would ordain Orthodox women as rabbis. But the Orthodox she-rabbi is really just a byproduct of the program, not the point of it. The non-denominational program is intended to train a new crop of Jewish educators, to teach in Jewish day schools, not to take on pulpit positions. In bestowing the title of rabbi on its graduates it will be invoking the original sense of the word — teacher.

Rabbi Donniel Hartman, co-director of the institute and the son of its founder, Rabbi David Hartman, told the Jerusalem Post, “We think the title ‘rabbi’ is important because in the Jewish tradition, the highest level of educator was given the title rabbi, which literally means teacher. Today, the top-tier educators seek the title of rabbi to reflect their status as well.”

And, the thinking goes, women who have the same high level of knowledge should get the same title, and the same status that goes with that title. Makes a lot of sense. But that title, as treated by the Hartman Institute program, is more akin to Doctor for a Ph.D. than for an M.D. Just as one wouldn’t trust one’s English professor to take out one’s tonsils, one isn’t meant to trust these rabbi-educators with decisions about Jewish law:

“This is a smicha [ordination] program that is not built around the classic learning of Jewish law, rather on the ability to communicate the central ideas of Judaism in an inspiring and meaningful way for the next generation of youth,” Hartman continued.

That is, the Institute’s rabbi graduates will have no authority in Jewish law or ritual life. Which is why the ordination can be non-denominational and why the modern Orthodox (but very liberal and feminism-friendly) Rabbis Hartman can get away with “ordaining” women. Still, the move has caused quite the uproar in some circles, and could certainly be a stepping stone toward full ordination of women as Orthodox rabbis (whether or not that’s one of the Institute’s ulterior motives — wink, wink ;-).

But is it good for Orthodox women? Samantha M. Shapiro ponders this question in Slate and points out the tough spot in which Orthodox women who seek the highest levels of Talmudic knowledge and, God forbid, the title “rabbi,” find themselves (that spot’s often called “between a rock and a hard place,” but in this context something like “between the bimah and the mechitza” seems more fitting). Shapiro makes the excellent point that, in Orthodox circles, women can often make more inroads into positions of responsibility and authority by not being called “rabbi.” For a woman, bearing the title is too brazen, too out-of-step with the status quo, for the community to be able bestow its trust and respect in her. It’s like walking into shul in a red halter dress (or with a big scarlet R around your neck). No matter how fervently you say your prayers, no upstanding Orthodox mother’s gonna want her son to marry a floozie like you. You have to be more subtle and modest to get what you want. Make them think you’re a good girl. Then you can pull out the handcuffs on your wedding night.

–Rebecca Honig Friedman

- 5 Comments

January 24, 2008 by admin

But Really, How Jewish IS Amy Winehouse?

Q. Amy Winehouse…

a) makes pretty great music.

b) is a crack-smoking trainwreck.

c) is Jewish.

The answer, as you probably know, is all three, and the media is obsessed with each of these factoids. After the release of a video of Winehouse doing various drugs was greeted with requisite shock and a reprise of “is she or isn’t she in rehab?”, I started thinking a little more about (c). In the face of the singer’s unraveling (about which there’s hardly need for yet another commentary), it’s become impossible to ignore just how psyched everyone seems to be that Amy Winehouse is Jewish.

There are different motivations behind this, of course. Both the ravenous press and Winehouse herself have joyfully portrayed her Jewish identity as a bizarre contrast with her bad girl image. The Jewish community, ever-eager to claim a celeb for the team, has managed to boast and sneer about her at the same time. Winehouse is the proud – and in many ways, welcome — antithesis of the “nice Jewish girl,” but since she does tend to identify with two out of the three elements of that little saying, both she and the media like to keep her options open.

Here are the oft-repeated basics. Back in 2004, The Guardian was one of many publications to pin her as “a slight 20-year-old Jewish girl from north London” and The Telegraph wrote, “Done up to the nines (lustrous lipstick, dark mascara, long black eyelashes, thick black hair), Winehouse looks every inch the Jewish princess.” In March of 2007, Rolling Stone‘s blog noted that “Ms. Rehab might in fact be the highest-debuting-female-solo-British-tall-Jewish-black-haired-tattoed-with-a-birthmark-on-her-left-arm artist ever to make the U.S. Billboard charts.” In May, the Toronto Star chimed in: “The beehived, heavily tattooed Winehouse might be a wee Jewish girl from North London, but she can snarl and wail like Etta James or Eartha Kitt.” From a Rolling Stonecover story that same month: “Those who have only heard her voice express shock upon seeing the body that produces it: The sultry, crackly, world-weary howl that sounds like the ghost of Sarah Vaughn comes from a pint-size Jewish girl from North London.” And from the Washington Post: “Winehouse has an exceptional voice that’s even more striking when you catch a glimpse of its source: a wispy, heavily tattooed young Jewish woman with a mile-high beehive for a hairdo and a Gothic level of mascara caked onto her face. It almost doesn’t compute.”

What a study in contrasts!

When she’s prodded to comment on her bad girl ways, Winehouse tends to bring up her Jewishness herself, offering it as a reassuring counterpoint to the rest of her image. “She says what she really wants to do in 10 years’ time is to settle down and be a good Jewish mum,” Australia’s Sunday Times reported last summer. The paper went on to quote the singer as saying, “I would like to uphold certain things, but not the religious side of things, just the nice family things to do. At the end of the day, I’m a Jewish girl.”

The news that Winehouse planned to have a traditional Jewish wedding ceremony and (bonus!) convinced her husband to convert, had the press slobbering.

After music producer Mark Ronson laughed off rumors that he and Winehouse were having an affair, he shared this highly pertinent information: “Amy makes a really nice meatball dinner. She’s good at making Jewish mother food.” More recently, he announced that he and Winehouse may team up to do a holiday album that will include ditties with names like “Kosher Kisses.”

Because all of this is not enough, the Jewish Chronicle recently posted a short write-up entitled “How Jewish is Amy Winehouse?”**

In what I can only assume is a very (very, very) lame attempt to be funny, the piece manages to embrace stupid stereotypes in the name of policing Jewish identity. In the “pro” column, “Amy is on record as saying she loves her grandma, she likes to make roast chicken on a Friday night and looks forward to a matzah and edam sandwich after an evening out.” On the con side, she has all those tattoos “(of naked ladies, no less)” and, you know, drinks a lot. The verdict? “Once she comes out of rehab, we’ll have her back,” the Chronicle reassures. “So we say she is 78% Jewish.”

What a relief! Now we know.

**”How Jewish is…” looks to be a recurring feature at the Chronicle, which also put French President Nicolas Sarkozy* on the hot seat. The results? His grandfather was Jewish (before he converted to Catholicism – but “we have made a halachic decision not to recognise it,” says the Chronicle)! He can boast of family members who died in the Holocaust! And woah, his girlfriend Carla Bruni once recorded a song written by Serge Gainsbourg, a bonafide Jewish person!!!

–Eryn Loeb

- 23 Comments

January 23, 2008 by admin

The New Jew Food?

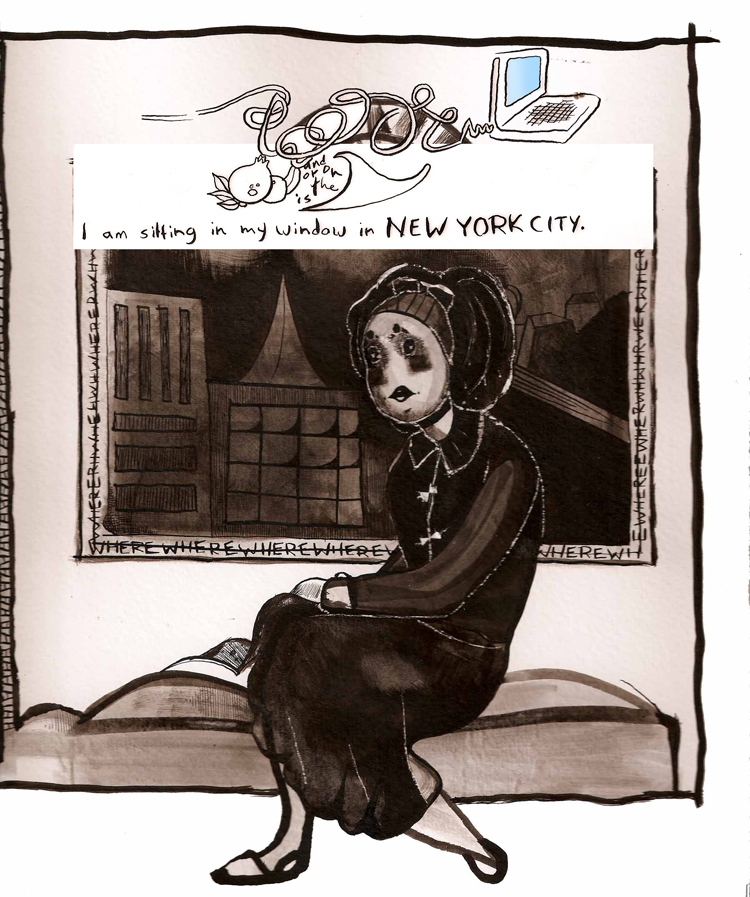

I’ve been doing a lot of cooking lately. In comparison to the stereotypical “I use my oven as an extra shoe closet” New Yorker, I’ve

probably always cooked a lot for this city. But since I started freelance writing two days a week last summer, and especially since the New Year when I renewed my commitment to preparing my own meals, I’ve found myself spending much more time in the kitchen.

I’ve also discovered that there’s lots of time to think when one cooks – even if NPR is playing in the background. As I’ve tinkered with various types of cookies and tried out new recipes from my favorite Chanukah present, Veganomicon: The Ultimate Vegan Cookbook (thanks Mom!), I’ve started to wonder, “what makes food feel Jewish?”

Yes, there are the old standbys – Chicken soup with matzah balls, fresh challah, pastrami on rye. And then there are the mysterious, and often severely unappetizing foods that you find in the “kosher food” section at the supermarket – gefilte fish, pickles, Manischewitz, and Tam Tam crackers. Honestly, I can only imagine what folks who aren’t familiar with Jewish eating must think when they see a supermarket shelf of glass jars filled with gelatinous objects suspended in a bunch of different colored murky liquids.

But when I fast forward to THIS century, and I start to think of all my amazing Jewish (and Jewishly committed) friends – friends who are worldly eaters, friends who are vegetarians, pescatarians and ethical meat eaters, gluten-free, local-food advocates, friends who are both Ashkenazi and Sephardi – the supermarket borscht just doesn’t seem to capture the breadth of their eating habits. So, does that mean that my Jewish friends just don’t eat “Jewish food,” or does it mean that the typical understanding of “Jewish food” hasn’t caught up to the Jewish people who eat it?

Two weekends ago, I made a Shabbat dinner for friends. I made vegetarian three-bean chili in my slow cooker, whole wheat challah, and a jicama and tangerine fruit salad, and an apple pie with a crumble-top crust for dessert. We ate it with store-bought hummus, pickles jarred by my friends (local Jewish farmers) and

artisanally-crafted cheese. Except for the challah and pickles, my bubbe probably wouldn’t recognize any of the foods I made as “traditional Jewish foods.” But to me, the meal couldn’t feel more Jewish – it was homey, and warm and brought friends and family around a table to celebrate Shabbat.

I think that the definition of Jewish food is changing – or needs to change – to include the way we eat today. Perhaps the iconic foods will stick around and my children will someday serve potato kugel to their families, but I truly hope that the spring vegetable matzah lasagna, or the roasted root vegetables I make in the winter make for Passover make it into the canon as well.

Rabbi, Chef, and food historian Gil Marks described what he thinks makes food Jewish on a recent PBS special on American Jewry. He focused mostly on tradition and the time-tested recipes our mothers and grandmothers made throughout history. I’m a big fan of Rabbi Marks, but I also think that defining Jewish food in this century is up to all of us. So – I’m wondering – what makes food feel Jewish to YOU?

–Leah Koenig

- 3 Comments

January 21, 2008 by admin

The Winter Issue is Up!

Lilith’s Winter 2007-2008 issue is out, and we want to hear your thoughts! Please make sure you say what article you’re responding to, and leave your comments below. (If you’re having trouble leaving a comment, you can send it to us at info@lilith.org and we’ll post it for you.)

- 4 Comments

January 17, 2008 by admin

Running Commentary

I was jogging in Jerusalem on Rehov Yaffo on Saturday night when I was harassed by a hasid. Well, I’m not sure if it was really harassment proper (by which I mean harassment improper), but it was an unwelcome comment. The man, who was wearing a long robe and a streimel, called out to me, “Why do you have to do this here? Where are you running to?” grunting disapprovingly. I was modestly dressed in long pants (to the extent that pants can be modest) and a long-sleeved T-shirt, and I even had my hair braided underneath a kerchief. And yet my presence still disturbed him.

I was about to quote to him from Pirkei Avot and ask him why he was talking to a woman (which is discouraged by R. Yossi ben Yochanan), but I had a better idea. Having recently completed a masechet of the Talmud, I knew by heart the formula for the Hadran, the prayer traditionally recited upon completing a significant unit of text study. Much of this prayer compares “us” to “them” – “we” study Torah, while “they” engage in idle pursuits:

*We express gratitude to you, God, that You have established our portion with those who dwell in the study house, and have not established our portion with idlers. For we arise early and they arise early; we arise early for words of Torah, while they arise early for idle words. We toil and they toil; we toil and receive a reward, while they toil and do not receive reward. We run and they run; we run to the life of the World to Come, while they run to the Well of Destruction.*

“To the Well of Destruction” in Hebrew is “l’ve’er shachat,” which is what I hollered over my shoulder to the Hasid who asked me to where I was running. I wish I could have seen his face, and I wonder if he shared this story when he arrived, surely less breathless, in the World to Come.

–Chavatzelet Herzliya

- No Comments

January 16, 2008 by admin

Jewish Metadata: Suggestions for the Womb

Is there any other ethnic or religious group that devotes as much time, effort, and money to thinking about itself as the Jewish community does?

As a people, we are so “meta.” Case in point: The Jewish People Policy Planning Institute (JPPPI) releases an annual report on the state of the Jewish community, with suggestions for improvement. (Another case in point — the fact that there is a Jewish People Policy Planning Institute, and numerous other organizations with similar concerns).

2007’s report finds Israel placing a less central role amongst Diaspora Jews, a largely cosmopolitan bunch who aren’t as wealthy as one might think we are, and who are often in mixed marriages but also often raising their children Jewish (the Jewish Chronicle has a good summary of the report’s findings but you can read it in its entirety on the JPPPI website). Still, the JPPPI’s main suggestion for improvement? More Jewish children. Seems the ancient precept of p’ru u’rvu [be fruitful and multiply] is still the best advice they can come up with. And they would have the community give middle class families financial incentives to have a third or fourth child.

Can you say Big Brother?

Almost a year ago, I wrote about a debate over a similar suggestion to increase childbirth in Israel (JPPPI focuses on the Diaspora) and sided with the demographics researcher rather than the feminist who told him to “spare my uterus your fancy ideas.” Yet, now, maybe because of the mention of money and the desire to put this demographical theory into practice, this suggestion makes my skin crawl. There’s something about using children for a cause that’s just yucky, not to mention the increased social pressure (already so intense in the Jewish community) to have children.

The suggestion reeks of desperation — typical Jewish anxiety over the destruction of our ranks — and there’s nothing less attractive. As a people seeking to attract new members, and keep existing ones, we need to get beyond it. Don’t pay people to have children, pay to create communities and programs that will make the children they do have, of their own volition, want to stay.

–Rebecca Honig Friedman

- 2 Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...