Lea Grover

The Books that Taught Me to Love My Body Hair

When I begged my mother to teach me to shave my legs, I was nine years old. “Your body hair is normal,” she said, “And it’s not healthy to worry so much about it now.” That was easy for her to say. Her pale legs never had visible hair to my eyes, whereas my legs looked more like my father’s, and my older sister’s, legs descended from my father’s people, from women like my mustachioed grandmother. My legs were as pale as my mother’s, but the hair that grew on them was blacker than the hair on my head and filled me with shame whenever a classmate pointed or laughed as the playground grew warmer and shorts became the clothing of choice for the nine-year-old set.

Still, she taught me as best she could. And she taught me to shave my armpits, while she was at it, standing in her three-quarter bathroom, with our feet raised onto the closed toilet lid.

I remember this in the hazy way of memory with import but without emotion. It is not a happy memory, but not sad, either. It is simply a recollection of an event. The same cannot be said of the day my so-called “best friend” held me down on her bathroom floor and shaved my rear, laughing that I had “a hairy butt,” and that no boys would want to make out with me if I didn’t “fix it.” I was 12.

The fact that hair grew anywhere aside from my scalp and my eyebrows was an offense, and even those hairs grew thick and unruly. During sleepovers, fellow well-meaning tweens attempted to pluck the hairs along the ridge of my eyelids, and I struggled not to flinch as my eyes watered from the pain. I wanted so badly to look like them, to fit in with them, to not be my grandmother’s child, not my father’s child. I wanted to be the blond-haired nymphs of storybook illustrations. I wanted to be the models in magazines. I wanted to be everything I was not. But I was a Jewish girl with mountains of unruly black curls, breasts and hips erupting from my body in unwanted rounds, thick- calved, short, covered in hair that felt as thick as a pelt, unacceptable.

Just as strong as the memory of being shaved and humiliated is the memory of my first reading of The Mists of Avalon, by Marion Zimmer Bradley, when I was 13. Early in those pages, a teenaged Morgaine lies nude beside a man, and he plays with the fine black hairs on her thighs. On her thighs! I had never believed that having such hair was allowed, let alone capable of being the source of desire. I had to set the book down and breathe for many minutes before I could continue. The hair on my body, that had so shamed me through my early adolescence, was supposed to grow.

How was I to know this was normal? I had never seen a woman with hair on her thighs. In every trip to the beach or pool, every hypersexualized close-up in television or film, every Calvin Klein ad in a magazine, no woman had ever displayed hair on her thighs.

I stopped shaving. I embraced my body hair. I was fortunate that this coincided with the Lilith Fair, and a world in which women appeared in new magazines with hair under their arms and on their legs. In my school and on MTV they were usually the source of ridicule, yes, but those women didn’t seem to care. I went to my first rock concert, Ani Difranco, and the women around me had hair on their bodies, and with the thickets of their armpits and shins visible, they danced in the grass without shame. When I slipped off my overshirt and raised my arms in the air, hair visible beneath, nobody flinched. Nobody heckled. I was simply a girl in a crowd of girls and women, still darker and thicker and hairier than most, but at that moment I was all I had ever wanted. I was just like any other girl.

Puberty however, does not stop only because you make peace with some parts of it. As I neared the end of my teen years, the dreaded mustache of my grandmother began to make its appearance. I plucked, when I could tolerate the pain, and covered up with makeup when I thought I might be seen. I walked aisles of bleaching products, hair removal creams, women’s razors, and loathed myself both for wanting to try them and for being unable to spare the expense.

And then a college professor assigned War and Peace. As I read, again I experienced that thunderclap understanding, of being seen, the awareness that my whole life I had been lied to about what was natural, what was beautiful, and what was real. Tolstoy described his ingenue, his lovely young romantic lead, as having a beautiful black mustache.

Though my affection for both writers, Zimmer Bradley and Tolstoy, has been greatly diminished by learning the details of their deeply problematic lives, I still owe them my gratitude. That I came to a place in my life where the validation of men does not consume my self-esteem is thanks to these glimpses of bodies untouched by the modern expectations of sexuality.

I could be a woman with hairy legs and arms, with thick brows and a mustache, and I could be beautiful.

So when my daughters beg me to teach them to shave their legs and their armpits, I will teach them. But I will also read The Mists of Avalon and War and Peace with them, and walk before them to the pool with my legs covered in black hair, with the dark corners of my upper lip unplucked, despite their second-hand adolescent shame.

For now, while they are small, I spin around after the shower, my towel barely obscuring my lumpy, short, puckered, scarred, frizzy, hairy, perfect body, and I say to them, “Doesn’t it feel good to know how beautiful we are?”

Lea Grover is a work-from-home mother, writer, and member of the RAINN Speakers Bureau

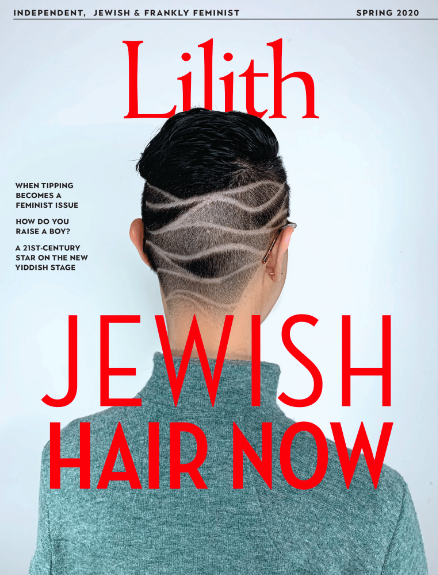

Jewish Hair Now.

The articles in this special section:

Waxing Nostalgic

Raina Lipsitz

My Mother’s Unshaved Legs

Talia Liben Yarmush

At the Beauty Parlor

Marianne Rogoff

Combing My Mother’s Hair

Ruth Knafo Setton

Hair-Pulling

Jamie Zabinsky

The Weight of Shiva

Sharrona Pearl

Head Covering: The Evolving Choices

Talya Jankovits

The Social Context of Hair: Hairstyles, Race and Status

Sarah Seltzer

HAIR IS PERSONAL. Hair is political. To make sense of

the social context of hair for Jews of color today, SARAH

SELTZER talked to CHAVA SHERVINGTON, a longtime

diversity activist in the Jewish community, as well as an attorney and mom,

who by her own admission has become “obsessed with hair issues” as she

helps her kids navigate the complex politics of their Black hair.

Please wait...

Please wait...