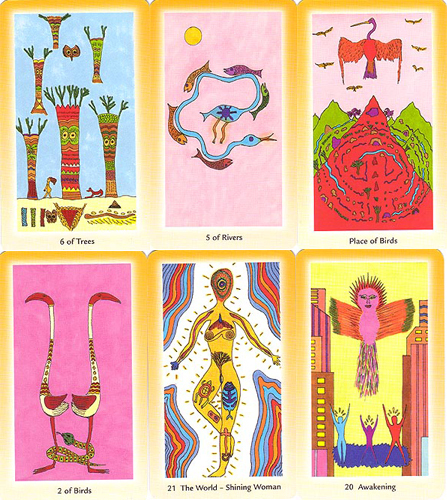

by Micah Bazant

Shul Matters

It’s Friday evening and I’m all set—I’ve packed my kippah, a map, and a clean white shirt. The boulevard is an ocean of cars and I am a stealth minnow on my bicycle, getting soaked, searching for the dome of the synagogue. I lock up my bike, enter the lobby and start stripping off my rain gear. I have prayers under my tongue and as I reach down for my kippah, I see a sign at the entrance to the sanctuary:

Please respect our traditional seating arrangement.

Men sit at the front, women at the back.

I read the sign and I respect it, although it does not even recognize that I exist.

I get back on my bike and head out into the rain.

I am not a man or a woman; I am a transgendered person with my own unique gender. When I am forced to choose between one of two options, a boy-oriented identity is what feels more comfortable and honest to me. However, as a person whose body is a mix of female and male characteristics, and whose gender expression does not fit into a rigid, socially acceptable masculine or feminine role, I often do not fit into most peoples’ ideas of “male’ or ‘female’. Internally, my sense of my own gender identity also does not fit into these boxes. Trans people are often made invisible. Many of us do not fit on either side of the mechitzah.

Transgender Jews

The articles in this special section:

Gender in Genesis

by Gwynn Kessler

Bet you didn’t know… what the Talmud says about Gender Ambiguity

by Alana Suskin

"It is unsurprising that rabbinic law treats the male as the norm and the female, by definition, as an anomaly—a deviation from the norm. Still, the sages do perceive women as human beings, creatures similar to men in important ways. Women are both 'like' and 'not like' men."

In The Image of God

by Danya Ruttenberg

Shul Matters

by Micah Bazant

“Today I am a Man” Takes on New Meaning

by Danya Ruttenberg

Please wait...

Please wait...