by Rabbi Susan Schnur

Our [Meaning Women’s] Book-of-Esther Problem

A 12-Page Lilith Feature By Rabbi Susan Schnur

“And the King sent letters to all the provinces, saying, ‘Every man shall rule in his own home.'” (Chapter 1:22)

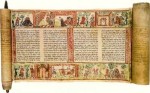

When is the last time you read the first two chapters of The Book of Esther? I mean really read them? They are so patently a polemic against women that it’s painful to think of Jews (especially young ones) at synagogues all over the world on Purim enjoying this dangerous induction into woman-hating.

Vide, chapter 1:16-22, in which one of the King’s officers responds to the fact that Vashti has refused to appear nude before a palace full of drunken males:

“It is not only the King whom Vashti the Queen has wronged, but also all the officials and all the people in all the provinces of King Ahasuerus. For this deed of the Queen will come to the attention of all women, making their husbands contemptible in their eyes, by saying: ‘King Ahasuerus commanded Vashti the Queen to be brought before him but she did not come!’

“And this day the princesses of Persia and Media who have heard of the Queen’s deed will cite it to all the King’s officials, and there will be much contempt and wrath. “If it pleases the King, let there go forth a royal edict from him, and let it be written into the laws of the Persians and the Medes, that it be not revoked, that Vashti never again appear before King Ahasuerus; and let the King confer her royal estate upon another who is better than she. Then, when the King’s decree which he shall proclaim shall be resounded throughout all his kingdom—great though it be—all the wives will show respect to their husbands, great and small alike.”

This proposal pleased the King and the officials, and the King did according to the word of Memuchan [his officer]; and he sent letters into all the King’s provinces, to each province in its own script, and to each people in its own language, to the effect that every man should rule in his own home.

Sitting in the synagogue, its standard issue annotated prayer book in my lap (the ArtScroll Family Megillah, edited by Rabbi Meir Zlotowitz), I scan the midrashic commentaries in the margins, which only add insight to injury. For example: “Vashti refused [to appear nude before the men], not because of modesty. The reason for her refusal was that God caused leprosy to break out on her, and paved the way for her downfall.” Whew. My teenage son leans over and whispers, “How about gang rape? Do you think something was wrong with Vashti because she didn’t like gang rape?”

When I saunter, newborn each year, across the pages of Rabbi Zlotowitz’s dependable marginalia, it’s like meeting up again with an old friend. “Thank you, Reb Z.,” I want to tell him, “for your spiritual largesse. For your misogyny and insensitivity, and for the constancy of your commitment to the moral low ground.” Sitting on my right is my very Conservadox 80-year-old mother who is also —not oxymoronically—a longtime board member of a women’s domestic violence shelter. “What?” I say to her, sensing that she’s getting hot under her collar, “Your Megillah is missing the commentary that talks about the terrifying threat of violence that accompanies male substance abuse?? Let me see that copy you’re using! What? It doesn’t mention the sexual sadism and degradation implicit in the King’s pimping??” She shooshes me.

My 10-year-old daughter elbows my husband and points to a midrashic note that explains that the King wanted Vashti to come to his party naked except for the “royal crown.” “Gross,” she synopsizes brilliantly. A moment later she adds, “That’s like what they did at that fraternity at Colgate. Vashti’s harem girls need to get together and do a ‘Take Back the Night’ like we do at camp. Hey, I’ve got an idea! Why don’t we do a ‘Take Back the Night’ right here in the middle of the Megillah reading?“

I whisper back, “Actually, that’s a clever idea.”

Soon we’re on to a section of the Megillah which describes the captivity rites in the girls’ harem, “six months of anointing with oil of myrrh, and six months with perfumes and feminine cosmetics,” after which each girl goes to the King “in the evening” and “the next morning she would return to the second harem.” I look over at my pre-pubescent daughter and see that she’s again reading the helpful commentary: “Having consorted with the King, it would not be proper for them to marry other men. They were required to return to the harem and remain there for the rest of their lives as concubines.” Again I thank Rabbi Z. for the exquisite sharing of his knowledge of ancient Persian sex etiquette as well as his pornographic fantasies, and for causing me to sink into this personal trough of sarcasm and bitterness, which I hate.

What are contemporary Jews supposed to make of a religious text that dishes up such disturbing garbage? Most Jewishly committed women I know, even feminists, solve the problem of these offensive narratives (rabbinic and biblical) by fighting valiantly to stay in denial. So, okay, we feel upset for a minute, but then we think, achh, Purim, it only comes once a year, don’t start. .Just don’t start. Shoosh yourself.

When, though, I wonder, will women finally create a morally defensible re-write of these chapters? Why aren’t we insisting that our synagogue communities cheer and stomp their feet at the mendon of Vashti’s name? She is a fore mother in the best sense of the word—assertive, appropriate, courageous. My educated supposition is that the full moon of Adar—now the date for Purim—used to be a pagan occasion for autonomous women’s rites that could not be reined in by men, and that these chapters, therefore, represent one of Purim’s many core ‘reversals;’ that is, they represent a male revolt against women. Yeah, I think, looking around the room, but why does it feel like our row in the synagogue is the only one that gets this?

As the children around me flail their graggers, I think about how participating in this public reading of the Megillah represents our complicity in the degradation of people, and about how I, for one, should figure out how not to sanction this anymore. I think back a decade or so to the year when the Hebrew day school principal gave all the “beautiful Esthers” (that is, every single female child in the costume parade) Barbie dolls. (I tried, but failed, to engage our rabbi in a discussion about this.) And then I remember the year after that, and the year after that, and the year after that….

Nineteen years ago, in these LILITH pages, Cynthia Ozicit dropped an early feminist bomb: She called the disenfranchisement of females within Judaism “mass loss,” “the amputation of half its potential scholarship.” There is no “Jewish genius,” she said, only a Jewish “half-genius,” which is not enough for the people who claim “to hear the Voice of the Lord of History. We have been listening with only half an ear, speaking with only half a tongue, and never understanding that we have made ourselves partly deaf and partly dumb.”

Since then, we women have worked hard to be represented as females, in Judaism: We are cantors, scholars, mothers, davenners, teachers, writers, rabbis; we have created female institutions for study and prayer, egalitarian re-writes of liturgy and texts, feminist reconstructions of Jewish fore mothers, etcetera. But still, at the base of it all, we live with many Jewish texts whose core agonistic purpose was to censure women’s rituals, to decry deities that uplifted females, to erase antecedent women’s history, to derogate and render invisible women’s intimate empowering relationship to the earth’s cycles and generativity, and, in general, to set—in concrete and steel beams (over the rubble of feminine experience)—the foundations of patriarchy. It is high time for women and sympathetic men to be challenging this, to be educating ourselves, for example, in the prebiblical Zeitgeist, so that we can best remediate some morally reprehensible Jewish texts (not only, of course, in relation to women).

Doubtless some of us female rabble-rousers have already been called ‘pagans,’ ‘idolaters’ and ‘polytheists’ for our attempts to unearth the women-positive rites, attitudes and theology that lie crushed beneath Hebrew Scriptures. These accusations are, of course, silly, but they intimidate us nonetheless because we have internalized, after all, our dispossession.

Let me say that Jewish women seeking feminine antecedents don’t ”believe in the goddesses” whose pentimenti can be seen behind some Jewish texts (like Ishtar, for example, Esther’s namesake, who lurks behind the holiday of Purim), nor do we fail to recognize the developmental importance of monotheism. We are saying something different (that has nothing to do with ‘worshipping idols’): that we are no longer willing to throw out the pink-ribboned baby with the bath water. The fore mothers of Esther, Eve, Sarah and Miriam were female deities—Ishtar, Lilith, Meri, the Queen of Heaven and others. There was once a theological language and a set of rites that uplifted women and brought us self-esteem and authority. That’s the pentimento we want to scratch away at, that’s the part we are clamoring to uncover and reclaim . . . so that it’s good for us, too.

In Regina Schwartz’s new book. The Curse of Cain, she struggles with the two sides of the Bible. On the one hand, she writes, the Bible is a text that has a humane “accountability for the widow, the orphan, the poor.” On the other, however, it’s a text that models a religious commitment to genocide—for example, “obliterating the Canaanites” (fill in your word of choice here: Hutu, Copt, Cherokee, Muslim, kulak, Croat, Jew). Hebrew Scriptures were also fairly committed to the cultural genocide of the feminine— because the latter threatened the nascent, ever-shaky and castratable Israelite patriarchy. The Hebrew God’s human male “children,” in Scriptures, are fairly consistently defined against inferior others, including us females.

All of this is just to say that the Megillah is a good example of a Jewish text that’s deeply interested in this idea of insider vs. outsider. Not only is Haman an outsider, but so are women and women’s natal theological families: that is, our .sustaining myths, our bodies, our primordial connection to nature, our female initiations. That’s all off limits. To this day, text-sanctioned history means that it is “heresy” for women to inquire after “our” side of the family, after “our” side of the past. In some ways, the Hebrew Scriptures is an intimidating, ungenerous book, and its self-interested defenders can be ungenerous and intimidating, too.

So, dear readers, hazak v’ematz, be strong and take courage. As Mordechai once said to Esther (chapter 4:14): “If you persist in keeping silent at a time like this … you and yours will perish. And who knows whether it was just for such a time as this that you attained your elevated position?”

And Esther looked him straight in the eye and answered, “Gotcha.”

Our [Meaning Women’s] Book-of-Esther Problem

The articles in this special section:

The Womantasch Triangle

by Susan Schnur

"The figures of Vashti and Esther, clearly in origin full-moon prespring relatives of the ancient mythological life cycle goddesses, come down to us, in the Book of Esther and in rabbinic midrash, so disfigured and devalued that it is hard to know how to begin resurrecting them.

But let's start with Harvard psychologist Carol Gilligan, whose research shows us that females' self-esteem is highest before puberty, but then we turn into women, males enter our consciousness, and it all goes to hell."

Please wait...

Please wait...