by Gwynn Kessler

Gender in Genesis

And God created man in His image, in the image of God He created him; male and female He created them (Genesis 1.27, JPS translation).

So God created the human/humanity (ha-adam) in God’s image. In the image of God, God created him/it: male and female God created them (Genesis 1.27, my translation).

Genesis 1:27, for all its brevity, is difficult to translate—the original Hebrew eludes our easy understanding. Because of this difficulty, we often ignore this account of human creation altogether, concentrating instead on the other, more familiar account of human creation—in which woman is created from man (Genesis 2:21-23). We forget that there is any other biblical paradigm for thinking about the creation of humans and gender, even though the Hebrew Bible itself repeats Genesis 1:27 practically verbatim at Genesis 5:2.

In part, the difficulty decoding Genesis 1.27 stems from its fluctuation between singular and plural, and from the lack of punctuation in the Hebrew Bible. Seemingly slight differences in punctuation can alter our understanding of a crucial question: how does the phrase ‘male and female’ relate to the phrase ‘in the image of God’? In my translation of the verse, I suggest that not only did God create human(ity)—male and female—in God’s image, but that God’s image is both male and female.

During the rabbinic period (lst-7th centuries CE), some of the rabbis resolved the problem of the two creation stories by understanding the first human as a two-sexed being (androgynes), who is then quite literally split into two differently gendered beings (Genesis Rabbah 8:1; Leviticus Rabbah 14:1 and parallels). This interpretation reflects, and simultaneously helped to construct, certain ideals about gender differentiation during the rabbinic period.

As transgender Jews and allies look to our traditions, we can now ask again what becomes of the first human; male and female? Can we read our texts in order to reflect, and simultaneously help construct, new ideals about gender for our own society? Perhaps we can. First, we can note that according to Genesis Rabbah 8:1, even though adam is split into two separate genders, God remains one: both male and female.

Furthermore, we might stress that Genesis Rabbah 8:1 records another interpretation of adam in which the first human is a “golem”—an undifferentiated, perhaps ungendered, being. That this undifferentiated adam is created in God’s image provides us a model for a God who trans (cends) gender altogether—a God who is both male and female, meaning neither

Although Genesis Rabbah 8:1 does not imagine a world where a person who identifies as both female and male can refuse to be split in two, we can work to shape a world where ze proclaims hir creation in the image of God. Even though Genesis Rabbah does not envision a world where a person might choose to identify as neither female nor male, thus existing outside of a rigid bi-gender system—we must affirm all gender expressions and identities.

I began by stating that Genesis 1:27 is difficult. What I mean to say is that Genesis 1:27 is complex. In fact, what is most queer about this verse is its ability to challenge—or dare—us to understand it easily. It prophecies, as it were, gender trouble. This verse, which at least mythically purports to usher gender into the world, simultaneously canonizes gender ambiguities.

Gwynn Kessler is an Assistant Professor of Religion at the University of Florida, Gainesville. She received her Ph.D. in Midrash from the Jewish Theological Seminary in May, 2001.

Transgender Jews

The articles in this special section:

Gender in Genesis

by Gwynn Kessler

Bet you didn’t know… what the Talmud says about Gender Ambiguity

by Alana Suskin

"It is unsurprising that rabbinic law treats the male as the norm and the female, by definition, as an anomaly—a deviation from the norm. Still, the sages do perceive women as human beings, creatures similar to men in important ways. Women are both 'like' and 'not like' men."

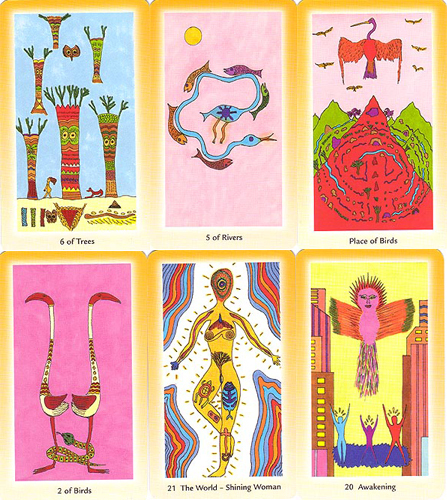

In The Image of God

by Danya Ruttenberg

Shul Matters

by Micah Bazant

“Today I am a Man” Takes on New Meaning

by Danya Ruttenberg

Please wait...

Please wait...