Ruth Efroni, translated by Ilana Kurshan

Fiction: That Dad with White Socks

Third Prize in Lilith's 2019 Fiction Contest

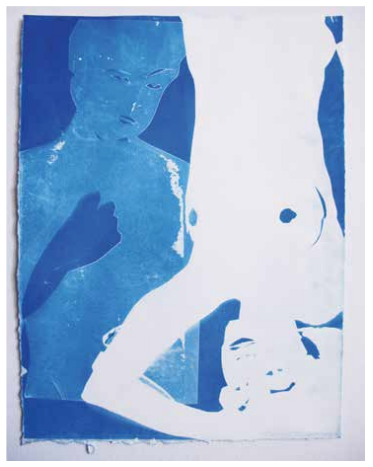

Art: Ofri Cnaani

So there’s this dad in the kindergarten (yeah, that’s how mom porn begins) who takes off his sneakers in the hallway and enters the room in socks. He’s the dad who sits there every morning at the art table with his curly-haired daughter, drawing monsters. The girl says, “Make her nose like this and her legs like that,” and the dad does the opposite, and her curls bob up and down in protest and delight.

Sometimes my kid too wants to draw a picture with Mom. “Sure, kid!” I say, feigning enthusiasm. “What should we draw today? An elephant? A dog? A boat? A hard-boiled egg?” Not that it matters what my kid decides, it always ends up looking like a tree house. But the kid is always happy with my giving tree, as if it were the first time he’d laid eyes on such a masterpiece. “It’s great, Mom,” he says. “Thanks, kid,” I say.

“When your dad was a little boy, he had the most incredible tree house,” I say out of nowhere, still drawing. “That’s where he was, high up in his tree, when he saw me for the first time. He was six and I was six and a quarter.”

Sol remembers the unfamiliar Peugeot that parked next to the moving van, the back door that swung open, the girl who emerged from the car wearing a wide-brimmed hat that covered her face. He followed her with curious suspicion as she stood tall and made her way slowly down the path leading to the new house that had been built in the adjacent yard. “Tell me more,” I once asked. “That’s all I remember, Ruta,” he answered. “So tell me again,” I insisted, like a little girl listening to the story of her birth. I’ve heard this story so many times that sometimes it seems like these are my own memories. Not his. I imagine that I made my way down the path slowly, in protest. That I was fighting back tears. That the moment I lifted my eyes to take in the height of my new house, the boy in the tree retreated further into the branches, improving his hiding spot. It took me an entire childhood to discover him: From the other side of the honeysuckle fence I watched as each of his baby teeth fell out, one after the other, during a single Passover vacation. For three years I followed an ugly bulldog print on a blue T-shirt, which stretched tighter and tighter across the neighbor’s son’s growing chest until I could swear that the bulldog was baring his fangs. Or grinning. I was there when a chronic cold sealed his nostrils shut with a thick greenish crust that mesmerized me each year, from January to April. In eighth grade I smelled the pungent odor of sweat and hormones he emitted until someone (who?) told him about this thing called deodorant and suggested he should give it a try. He flashed past me on his light silver race bike, his hands crossed over his chest like a genie who would someday grant all my wishes. At age 16 I saw him blush when I adorned myself in my new black jeans with a jewel on my butt.

Now I squint to catch sight of the white socks of the dad sitting across from me. They are new and soft, and suddenly I’m overcome by a desire to invite them to climb up the rusty ladder of my tree house. Even just to see if I still have it in me. You’re already an auntie, I remind myself, jolting myself back to reality. Aunties don’t live in tree houses. They have other games for aunties. Like the counting game. The game goes like this: The aunties walk down the street and count how many looks they can collect. It’s not that anyone turns their heads or whistles or anything like that, heaven forbid. That no longer happens to them. I’m not even talking about smiles. No, they count stolen glances, the slightest suggestion of a nod, that faint sign of recognition that serves to acknowledge their existence. Their existence as women, I mean. In Israel this game is fairly straightforward, because when you look someone in the eye, they look back at you. It’s automatic. In America it’s a bit trickier, because guys are more civil and less macho. If you happen to exchange glances with an American, they’ll wave at you and offer hearty greetings and actually say something like “gorgeous morning,” which violates the rules of the game big-time and only confirms the fact that you’re indeed already an auntie, that you have no secrets anymore, that there’s no need to hide anything that happens between you and some stranger on the street, that everything from here on out is prim and proper and pathetically boring.

And even so there are days when I manage to rack up points. I keep track of them with a clicker, like a dog trainer. A look—click! Another one—click! That’s how I count them in my head. The man at the diner on Saturday morning, sitting next to his sullen wife—click! The guy with the trail of aftershave and the double stroller I pass while jogging—click! The dreadlocked drummer downtown—click! And that’s it. Three is pretty darn good for one day. For my age. I’m already preparing myself for days of two. For weeks of one. For years of nada.

Under the table my eyes wander from the white socks to the lacey hot pink socks peeking out from my son’s sneakers. This morning, once again, the only clean pair he could find was his sister’s.

Do some laundry, auntie. Do it. Buy some wheat germ-scented hand cream. Take your kids to school in something other than pajamas. Have you noticed this is your last kid in preschool? That you’re a terrible artist? That your darling buds of May are blooming—near your bellybutton? That you’re on a losing streak in the counting game, auntie?!

The ringing of bells rouses me from the sorrowful litany of my life’s failures. ding-dong ding-dong, the teacher rings her little bell—a sign for baby chicks to flock to the blue rug. A sign for parents to take wing and buzz off. But where the hell are my wings. Bird? Houseplant! I wind my way from the classroom to the dim hallway, like the twisted stems of a Wandering Jew plant. What am I doing here in this foreign land, in the cold, in my dotage? “Father in heaven,” I cry out, “haven’t we Jews suffered enough?”

But there is light at the end of the hallway. That dad-in-the-kindergarten stands there, holding the door open. For me? Ask not for whom the bell tolls—it tolls for thee, auntie! Houseplant? Hell no! Light-footed gazelle. The pajamas become a negligee. I shake my darling buds of May with everything I’ve got. Who cares about my lack of artistic talent? Come on, what am I, in kindergarten? And by the way, sex goddesses like me don’t ever do laundry, certainly not socks. If anything, satin sheets. And just like that, to the sound of my fallopian tubas which are still tooting away, a soft wool hat covering my ears, I stand tall and make my way slowly down the hallway that leads to the brightly lit doorway, and when I cross it, for a split second, even less, for a nanosecond, the hem of his coat flutters over the eyelash fringes of my frayed scarf, and I don’t care who’s watching me from up in the tree house. “See you tomorrow,” the white socks say to me.

“Yes, tomorrow,” I say, and my clicker goes wild– click, click, click, click….

Ruth Efroni is an Israeli writer whose first book, Year of the Fox: Notes from the Diary of an Almost Proper Woman, came out in 2018.

Please wait...

Please wait...