Ruth Knafo Setton

Combing My Mother’s Hair

An erotic/sensual memory trip through crackles and changing colors of her hair. Heavy frizzy… foamy blonde… long wavy auburn… short Mamie Eisenhower bangs… little girl barrettes…. Still defiantly long and curling past her shoulders.

We tried to make her cut it as she reached a certain age (based on advice in women’s magazines). We forced her to go to the beauty salon with us, letting Mr. Paul raise his hands in horror: Erase that black! Too harsh! Too unnatural!

She emerged after six hours with a subtle sunlit auburn head of hair. Beautiful, youthful, but maybe too red, we thought. She looked in the mirror: it’s henna, she said. Just like henna. Within a week she bought her drugstore formula—jealously guarded through the years (one of us sent out to buy it so my father wouldn’t know) and voila! She tosses her black mane of hair at us, a gypsy flamenco dancer, a bullfighter.

The hair is thinning (but still thicker than ours). Such a dramatic color deserves dramatic clothes. My mother wears red, lime green, fire-orange. A hair breaks beneath the comb—still glossy black at the end, but pure white at the root. I look at the tiny bare spot on the scalp, almost imperceptible, and remember the sylph in tiny shorts and polka dot halter top of the 50’s.

Not too tight, she says, as I pull back her hair. Leave some curls on the sides.

Always coquette, always feminine.

I snap a beaded turquoise barrette around the ponytail and breathe in her hair. A wave from my childhood slaps me back. I smell the ocean in your hair: elusive salt and fresh sand smell, a grainy roar that fills eyes and nostrils. I smell the flesh of you too, always slightly damp it seems—fleshy and damp and pale—your Shalimar mixed with cooking smells: spices, cinnamon, vanilla—pungent herbs like cilantro and cumin.

I breathe you in and I’m on your lap again as we puzzle through the first American picture book I bring home from the school library. We tremble as we open the book to the first page. Flicka, Ricka and Dicka, pretty blonde triplets, smile back at us, beckon us into their safe black-bordered world where nothing evil can enter, no djnoun, no terrorists or Jew-haters, no rampaging mobs, no shrieking nightmare figures, no serpents with human heads. At least for now, we are safe.

In your hair too, I smell rage, my own impossible-to-control rage: at you, at life, at this world that made me who I am, a soft face hitting against a rock. I smell your own impotent fury at the teacher in Morocco who thrust your hair beneath ice water every morning to “get rid of those curls.” At the teacher who smacked your left hand with a ruler every day for a year until you managed somehow to write with your right hand—“but it was never natural, and now I write the way a chicken scratches in the dirt, going in every direction at once.” At your father who wouldn’t let the handsome boy (with heavy-lidded eyes and a curled lip like Elvis) court you because he was poor, and who took you out of school to marry Dad. At your mother who took two hour “beauty naps” every day while she left you with the younger brood of brothers and sisters to feed and bathe. They still consider you their mother.

Insular, self-educated, fearful and untrusting of strangers, c’est toi. I’ll go home later and find a note from you, scrawled in the same illegible hand, lines and words crowding, sliding off the page. Thoughts begun, never finished. You write me notes, phone me, leave me messages: was there ever anyone as alone as you? When you call me and leave a message on my answering machine, you never believe I’m not home: “Ruth. Ruth. Are you there, Ruthie? Ruth! Ruthie, it’s me, your mother. Are you there, Ruthie?” Until the message runs out.

I kiss the top of your head. Each strand evokes another memory, leads me down another path, as if your hair is a sea of unfathomable depths. Every time I dive, I discover clues that lead back to you, and I wonder where I begin and you leave off. Or perhaps that’s not even the question. Maybe all that matters is that I can breathe in your hair and remember—and here is what I wanted to tell you. Once, when I went to a writer’s colony for a month, my daughter wrote me a letter in which she told me that she slept with my hair ribbon tied around her wrist “because it smells of you, Mom.”

Ruth Knafo Setton is the author of the novel, The Road to Fez (Counterpoint Press) and the recipient of many awards. She has sailed around the world three times.

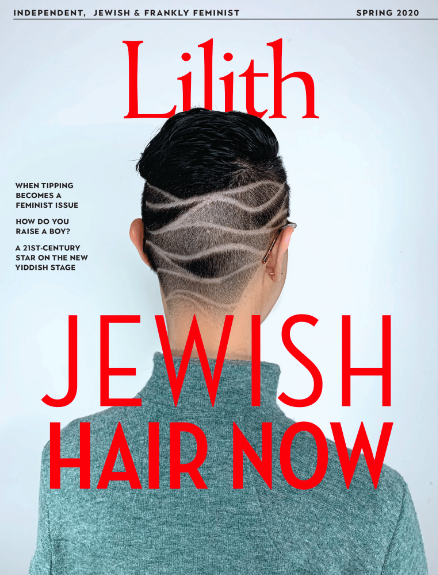

Jewish Hair Now.

The articles in this special section:

Waxing Nostalgic

Raina Lipsitz

My Mother’s Unshaved Legs

Talia Liben Yarmush

At the Beauty Parlor

Marianne Rogoff

Combing My Mother’s Hair

Ruth Knafo Setton

Hair-Pulling

Jamie Zabinsky

The Weight of Shiva

Sharrona Pearl

Head Covering: The Evolving Choices

Talya Jankovits

The Social Context of Hair: Hairstyles, Race and Status

Sarah Seltzer

HAIR IS PERSONAL. Hair is political. To make sense of

the social context of hair for Jews of color today, SARAH

SELTZER talked to CHAVA SHERVINGTON, a longtime

diversity activist in the Jewish community, as well as an attorney and mom,

who by her own admission has become “obsessed with hair issues” as she

helps her kids navigate the complex politics of their Black hair.

Please wait...

Please wait...