Tamar Fox

Choosing to Be a Foster Mom

Here’s a foster-care story that is uncommonly and intensely Jewish. One woman’s passionate account of why she does it — plus some bold suggestions about forming families.

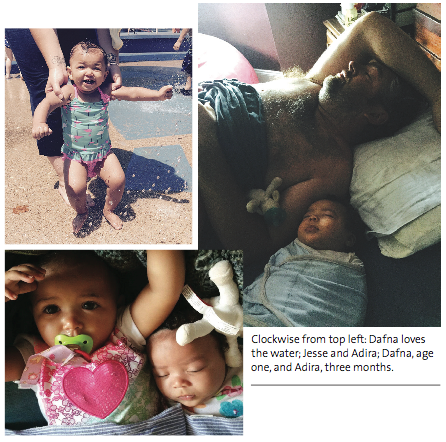

Tamar “breastfeeding” Adira.

In my biological family it is, ironically, becoming foster parents that runs in our genes. Because of my family history (more on that later) I feel a pull — much stronger than toward any other mitzvah — to foster children who need homes. Yet for most Jews, this is an issue that has fallen off our radar.

Here’s my story.

The city where we live — Philadelphia — has no dearth of children in need of homes. From newborn infants to teenagers, more than 100,000 children a year will have some contact with Department of Human Services, which handles child abuse and foster care. So in 2014, my partner, Jesse, and I began the process of becoming foster parents. We chose to foster through Jewish Family and Child Services, but at our orientation we were the only Jews signing up for this new role, and observant Jews were so unlikely to sign up to be foster parents that JFCS only offered training for foster parents on Saturdays; special arrangements had to be made to accommodate us.

We were fingerprinted, background-checked, instructed in CPR for children. We led social workers through our home, pointing out our smoke detectors and fire extinguishers.

Then, three months later, as I was cooking Shabbat dinner on a Friday afternoon, my phone rang, with a social worker from the agency asking if we wanted to take a one-month-old baby girl just being discharged from the hospital. Jesse was stuck in traffic. I was alone with this decision and my pot of soup, and I said yes, we would take her.

In the middle of our Shabbat dinner came a knock on the door, and…there was our daughter. Her medical records described her as “pink and irritable.” That first night she was exactly that. She wanted desperately to be swaddled, but with only three hours’ notice we were able to collect only the bare basics of newborn supplies — and that hadn’t included swaddles. We improvised with a towel, and the sash from my wedding dress to cinch her in, and — finally — this exhausted baby slept for a few hours.

Soon Dafna — the Hebrew name we chose to call her at home, in memory of my mother — went from pink to tan, and from irritable to relaxed. I started a new job. We found her a daycare spot. And twice a week someone from the agency came to daycare to pick her up and bring her to a supervised visit with her mother.

Dafna at one, Adira three months.

What did the separations feel like to me? Dafna was always returned to us from these visits wearing a different outfit from the one we’d dressed her in that morning. (I would not have bought her onesies saying “Mommy loves me,” and I cringed when she came home in them.) When her mom sent us notes in the diaper bag, they invariably soured my mood. When she gently requested that Dafna wear socks, or that she wear more layers, I rolled my eyes. I didn’t think I was a perfect parent, but I wasn’t struggling with addictions, I hadn’t given birth to a baby addicted to drugs.

But when I finally met Dafna’s mom, Mimi [a pseudonym], at the pediatrician’s office, I was humbled. It felt like we were all auditioning — trying to prove each of us was good enough to raise this child. I wanted Mimi to like me, she wanted me to like her, and we were both mostly worried about making sure Dafna was safe and happy. When the doctor was thrilled with her progress, we all celebrated, in a shared triumph that this baby girl was now thriving, despite her rocky start.

Dafna smiled easily, slept deeply, ate ravenously, and grew remarkably. At 4’11” I never imagined I would raise a child who would reach the 98th percentile in height, but Dafna’s legs seemed determined to reach the ground as soon as possible. And while Dafna grew, Mimi worked diligently to regain custody. She showed up for every visit, and every doctor’s appointment. When I was able to let down my guard a little, I had to admire how hard she was working for Dafna. She enrolled in Family School, a parenting program that met for classes six hours a day, two days every week. I couldn’t imagine spending 12 hours a week having people tell me how to parent; it seemed like a nightmare. But Mimi enjoyed it, and loved how much time she got to spend with Dafna. I saw that the baby was learning things in the classes, too.

Tamar, Jesse, and

Dafna, August 2014.

A judge, after six months, ruled that Mimi could have unsupervised day visits with Dafna. We met Mimi for these visits at a coffee shop near our house, and she was always precisely on time, or early. She brought everything a baby could need. She was warm and polite to us, and invariably overjoyed to see her daughter.

Gradually, gradually, I came to realize that Mimi was going to clear all the hurdles set up by family court. Privately, I had been hoping for her failure. Despite knowing that the goal of the foster system is to reunite families, I’d been wishing we’d be able to adopt Dafna. But watching Mimi with Dafna I knew they should be together, even as I felt my chest tighten with grief at the thought of saying goodbye to the baby.

As this probability increased, we prepared a ritual to acknowledge — to ourselves most of all — what this experience had meant. We needed to celebrate that Dafna was being reunited with her birth mother, and at the same time acknowledge the hole that her absence would leave for us.

On a Sunday just after Passover, our house filled with friends and family. We served Dafna’s favorite food, soup (we had seven kinds on offer), and created a short ritual based on the phrase from a baby naming wishing that a child will grow up to Torah, chuppah, v’maasim tovim. Torah, the wedding canopy and good deeds. In the ritual we told Dafna about the history of her name and how she came to be in our family. Then we erected a chuppah, representing shelter and peace, in our living room, and stood under it with Dafna. We sang a song together, and we all shared with Dafna our wishes for her, both big and small. We wished, among many other things, that she would go on to do good things for herself and for many others. We closed by singing Shalom Aleichem, because it ends with the verse, “May you go in peace.”

The day before my 31st birthday was the day a judge ordered that Dafna be reunited with her mom. It was a Friday, and before Shabbat came in we met Dafna and Mimi at the coffee shop where we’d done so many hand-offs before. We hugged Dafna and gave her blessings. As we said Shehecheyanu, praising God for sustaining us to reach this day, my tears leaked out. “Oh, this is not goodbye,” Mimi said to me, hugging me as I held Dafna. “We’re family.” And I believed her. I was sad to see Dafna go, but my heart was not broken. In a strange way, it was fuller than it had ever been.

A week after Dafna was reunited with Mimi, and had officially moved out of our house, we skipped synagogue to meet them at a playground on Shabbat morning. When Dafna saw us she threw her arms out and laughed with delight. We were overjoyed to see her, too. In just a week she already seemed taller, stronger, older. Mimi, Jesse and I stood around the swings, pushing Dafna back and forth. Her smile was enormous, and infectious. And then Mimi asked, “So, you aren’t going to foster again until the end of the summer?” The question sounded strange in my ears. Why should she care at all now that Dafna was back with her?

“Yeah,” I said, “I think we’re just going to take a few months to relax, and then go back on the list in September.” We were also waiting for me to have been at my job for one year, at which point I might be eligible for some paid maternity leave.

Mimi looked away as she spoke. “Oh. Well. It’s just that…my sister just had a baby girl, and I wasn’t sure if you would be interested in fostering her….”

For a small fraction of a second Jesse and I looked at each other, our eyes meeting in surprise and joy over the arc of Dafna in the swing. “Yes,” I said. “Yes, we’d love to.”

It took a month, ultimately, during which we played bureaucratic chutes and ladders with the private agencies. Think you’ve made progress? Head back to the start. Fill out paperwork, ask to speak to a supervisor, two steps forward, one step back. Promise again and again that you are interested in this child; it’s like you are trying to convert to Judaism and have to be ritually refused three times. Then one day a call came, asking can we take the baby tonight. And we said yes.

So less than one year into foster parenting, we’re nurturing the second infant from one family. Dafna and our new daughter, whom we call Adira (“powerful” in Hebrew, because she has such a powerful hold on our hearts and because it comes close to the meaning of the name her mother gave her) are first cousins — their mothers are sisters — and also second cousins — their fathers are cousins. And my seven-year-old stepdaughter, Jesse’s daughter, who lives with us half time, is delighted to have yet another baby to “mother” when she’s with us.

Now it’s the cries of little Adira that I answer in the middle of the night. Her forehead that I kiss, her angry puckered face that I comfort when she’s tired or hungry. And sometimes Dafna’s voice mixes with Adira’s, since we see Dafna often, keeping her overnight on weekends so that Mimi can work a late shift at her new job. We are family now, with this other family. Each day we knit our lives more tightly together. And each day these ties feel stronger, warmer, special — and strange. We have taken a baby into the intimate rhythm of our lives — and into our hearts — knowing that the relationship might not last.

So why do I do this? My own story as a foster parent is very Jewish. It starts with the Holocaust.

My grandfather escaped Vienna in 1938 on the Kindertransport. He was 14, which I always thought was unusual. I pictured the Kindertransport as being full of small children, not teenagers. But now I think how much worse it must have been for the teenagers, who knew exactly what kind of danger they were escaping, who had some sense that they were leaving their homes and would probably never be back, might never see their parents again.

When my grandfather, Walter, arrived in England, he was fostered by an English Jewish family in London, the Adlers. I don’t know much about them other than that they were in comfortable circumstances, that they had a maid. And that they saved my grandfather’s life. Without their sponsorship, it’s unlikely he would have survived.

Walter spent six months with the Adlers; after he felt confident in his English, he transferred to a technical college in Leicester. In 1943 he went to Cincinnati, where he was able to connect with his parents, who had also managed to escape the Nazis. Walter was drafted into the U.S. army and went back to Europe, first as an engineer and then as a translator for the War Crimes Investigating Team, which took statements from former concentration camp guards.

My mother grew up knowing this story, and was conscious that her own existence had been made possible by the Adlers. When I was a child she took me to meet Mrs. Adler when we visited England.

My mother’s life, too, was shaped by what she knew of the family’s history. In the winter of 1979, when my mother was 26 and a poor social worker, she and my father sponsored two refugees from Vietnam, Mai and Thai Tran, teenage siblings who had escaped Vietnam on a boat, living in a refugee camp in Indonesia until my parents, through the Jewish Federation in Chicago, brought them to stay in their living room. My dad got Thai a job, and now, more than 30 years later, the siblings still live in the Chicago area. Thai and Mai have flourished, in no small part because my parents sponsored them.

Sam Fox, Bev Fox, Thai Tran, Mai Tran, 1979.

But both of these examples from my own family’s history differ from my own experience in a salient way. My spouse and I, thus far, have been foster parents to newborns, and the bonds we feel for these babies are forged from different interactions than those of Mrs. Adler with a 14-year-old refugee or of my parents with Mai and Thai.

Some people, when they see my posts on Facebook or find out my relationship to the baby I’m bottle-feeding as I cradle her in my arms, ask whether we intend to have biological children of our own. Here’s why not: I am not in love with my Ashkenazi Jewish genes. My mother died at 55 of breast cancer, and given my family’s genetic history, my chances of living to 55 are low. I do not want to pass along these genes. So being a foster parent — and perhaps down the line becoming an adoptive parent- — is the route I’m taking toward motherhood.

And I’m encouraging other Jews to consider this option.

Evangelical Christianity has been promoting fostering as a means of spreading Christian gospel, sometimes employing strict parenting philosophies that include corporal punishment, and hostility to LGBT children. Fostering, to them, is a means of saving a body and a soul.

And some people living in poverty choose to foster because each child comes with a subsidy, a small per diem paid to the foster parents. Many of these foster parents are caring and wonderful, but living in poverty comes with its own stresses and possible traumas.

The infrastructure for Jews in the foster world is already present. The agency that certified us as foster parents is Jewish enough that it is closed for Jewish holidays (even the oft-forgotten Simchat Torah, and Shavuot). The non-Jewish intake worker who shepherded us through our certification made me laugh when she would call and identify herself as, “Keisha, from the Jewish.” Jewish family services agencies have a long history of helping foster children, dating back to a time when there were many more Jewish children in the foster system, perhaps as disease or childbirth claimed the lives of mothers in an earlier era, and fathers could not care for their children alone, or because poverty forced this choice upon some families. But as Jews have edged higher and higher into the middle class, fewer Jewish children end up in foster care. The institutions remain, now working mainly with other groups that suffer from poverty, sometimes complicated by drug and alcohol addiction.

I don’t want to — and can’t — paint a rosy picture of foster parenthood. There are so many times when I have felt defeated, depressed, or exquisitely furious at the way the foster system “works.” In Pennsylvania, new reporting laws have led to more children being placed in care, with no extra resources devoted to the system. In Philadelphia, children are falling through the cracks as new private agencies try to staff up. I’ve become accustomed to hearing the same truthful answer for each one of my questions: “I don’t know.”

All of which makes me wish that the Jewish community I know and love — the one that rallied to supply us with a month’s worth of meals after Dafna arrived with no warning, that cares about social justice, the one made up of many, many helping professionals like social workers, doctors, lawyers, rabbis — would bring their attention to children in foster care.

This year, when so many of my friends have been acknowledging their privilege, I have vowed to take my privilege and use every last bit of it to help get the best possible care for my two biracial foster children. I’ve called local lawmakers, written angry letters, passed around petitions, and bent the ear of anyone I could think of. Why did it take three months for Mimi to be given goals to work toward reunification? What exactly are the standards for foster parent training, and why did ours involve watching a VHS safety video that the trainer later announced was “probably out of date”? Why is there no centralized list of the resources and social services available to foster parents, from subsidized day care to free formula to help paying for music lessons or summer camp? Who is responsible for the fact that Adira arrived at our home with two pieces of paper, both of which had the wrong name for her?

Part of the reason I want the Jewish community to take up this cause is because I’m certain that the Jewish women I know would not stand for the level of dysfunction I see every day. Jewish mothers are known for being overbearing, even demanding. These aren’t considered positive traits, I know, but I sometimes daydream about how great it would be for some of the children in the foster system to live with a mother who cared for them in the extreme ways Jewish women are known for. I want all my white friends who have guiltily owned up to their racial privilege to cash that privilege in for access to lawmakers and agency heads. I want rabbis preaching about fostering from the bima. I want it to be something a wealthy family with a maid considers doing. I want it to be something a young newly married social worker talks her partner into. It has been like this before. Why can’t it be again?

Many of my friends are in the throes of building families, and some are struggling with infertility, or trying to figure out how to build a family as a same-sex couple, or as a single person. Adoption is expensive and can be risky, but it’s common in my social circles, while fostering is not. Certainly fostering has its own risks, but I wish it were at least on the radar for people thinking about how to create their Jewish families.

Jesse and I became certified foster parents just a few days before Passover in 2014, and when we finally reached this goal I thought, suddenly, of Moses. As a baby, Moses was at great risk, so his mother put him in an ark on the Nile, where Pharaoh’s daughter plucked him out of the water, and brought him up in the palace. It was a foster child who led my people from bondage to freedom. I don’t want to put any pressure on Dafna or Adira to become Moses, but I do wish my community stood by the water’s edge and plucked out some of the children floating by.

Tamar Fox is a writer and editor living in Philadelphia. Her children’s book No Baths at Camp, published by Kar-Ben, is a PJ Library selection.

Please wait...

Please wait...