The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

June 15, 2016 by Leeron Hoory

Rebecca Schiff Talks Technology and Illness, Volunteering to Be Objectified, and Writing What You Wouldn’t Say in Polite Company

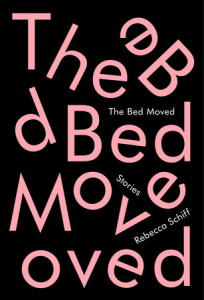

The Bed Moved is Rebecca Schiff’s debut collection of 23 short stories ranging from a few pages to a few paragraphs. Their language and voice are unique; sentences often end in ways that twist their beginnings. In “My Allergies Will Charm You,” the narrator opens with, “He had found me on the internet, and now I was going back to the internet.”

The Bed Moved is Rebecca Schiff’s debut collection of 23 short stories ranging from a few pages to a few paragraphs. Their language and voice are unique; sentences often end in ways that twist their beginnings. In “My Allergies Will Charm You,” the narrator opens with, “He had found me on the internet, and now I was going back to the internet.”

In “Communication Arts,” a teacher corresponds with students A, B, D, and Z, portraying a delicate and bizarre relationship between authority and vulnerability. Many of the characters make statements that are bleak in their honesty, revealing unintentional vulnerability. In “Third Person,” a few paragraphs paint a woman’s intricate but dissociated relationship to sex and connection: “Rebecca wanted to tell them not to worry, she forgot all the sex she had as soon as she had it, she didn’t really have it when she had it, and she hadn’t for a long time.”

The New York Times Book Review commented on Schiff’s compact language, noting her “almost Nabokovian boldness and crispness of phrase. Nabokov summarized a death in two words: ‘picnic, lightening.’ Ms. Schiff condenses a woman’s college years: ‘Nietzsche, penetration’.”

Often the characters are unintentionally funny. Many deal with illness and death. I met with Schiff in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, to speak about her book, the relationship between technology and illness, and the role humor can play when women write about difficult topics.

L.H.: Many of the stories in The Bed Moved are about coming of age, but at the same time they are inherently ironic, with a loss of innocence. How did you find this balance?

L.H.: Many of the stories in The Bed Moved are about coming of age, but at the same time they are inherently ironic, with a loss of innocence. How did you find this balance?

R.S.: I think we lose our innocence many times in our life. There is what we think about as the typical loss of innocence, like becoming a grownup, or losing virginity, but there are other kinds of innocence that we lose, about people and parents, and mortality. I was always scared of death when I was little, so I wasn’t exactly innocent about it, but I hadn’t had someone close to me die until I was in my 20s. I think losing a parent at a young age informed some of the loss of innocence portrayed in the book.

L.H.: I find the way you write about technology fascinating in the way it’s removed from technology itself, like in the story “http://www.msjz/boxx374/mpeg,” when a woman discovers her father, who has died, had a porn document on his computer. You write about how technology doesn’t just change our habits, but our relationships to others. What inspired your thinking about this?

R.S.: I think that when people die, there’s a weird way that people live on through technology, videos and photographs. There are memorials on Facebook pages, and people can still tag them and say, “I miss you.” The narrator in that story is looking at photographs on his computer for information, and then she finds something she didn’t expect to see. Technology makes us all kind of spy on each other. There’s less privacy, and people who are gone have even less, because they can’t control what’s still left for others to see. I was an early internet adopter, so I remember going online when I was 16, around 20 years ago, and going into chat rooms and talking about musicians I liked, so I’ve always been interested in it.

L.H.: “Rate Me” is a story about a woman who sends in her actual body parts to be scored. It’s strange and unsettling, but also painfully accurate in its commentary about objectification. What inspired it?

R.S.: What’s strange about this story is that the narrator is volunteering to be objectified; she’s kind of curious. I think there’s a mix where women don’t want to be judged about their appearance, but there’s this perverse desire to know. On online dating sites you can now rate people’s images on an attractiveness scale. There also used to be a website called “Am I Hot or Not,” so there are a lot of examples where people put their judgment of their appearance up to strangers. I like the idea of taking something that bothers me and in fiction going straight at it as a way of not being afraid of it anymore and overcoming my fear of it.

L.H.: Many of your stories use humor to talk about taboo subjects like death and sex, and yet I wouldn’t necessarily call them humor pieces. How do you envision the role of humor in talking about these subjects?

R.S.: Humor isn’t the only tool, but it’s one of the more powerful ones to talk about things that are difficult to look at in a sincere way. Some of it is not conscious, but just how I write. Some people think they have to be funny, and some people think they don’t want to be funny but they are so there’s a really wide range of the way that writers relate to humor. I think it’s a good tool for connecting with people and that’s also what fiction is about.

L.H.: A lot of the women characters in the book are very plainspoken about sex. Is that something you did purposefully? And what is your thinking about this bluntness?

R.S.: I’m pretty plainspoken about sex myself but I think the characters are even more so. It’s another chance in fiction to say things that you maybe can’t say in polite company. There’s a sort of a tradition like that with Jewish writers like Philip Roth, and a lot of writers were doing that in the ’60s like Updike, and Anais Nin, and other writers who weren’t Jewish necessarily. Roth was a big inspiration for me, because I read Portnoy’s Complaint when I was still in high school, and I saw how literature can be that straightforward about sex. I think that’s even more sexually explicit than my writing. I’m really interested in the ways that sex can fail us, too, as a way to connect.

L.H.: What are some of your literary and cultural influences?

R.S.: Well I mentioned Philip Roth. Grace Paley, who I’m rereading now, is an influence. George Saunders is an influence, and Lorrie Moore. I think she’s one of the funniest writers working today. She wrote a lot of short stories that took humor and made it central.

L.H.: The book is deeply personal but also speaks to a particular time of dissociation and women’s experience. What did you hope readers would take away from it?

R.S.: I think some of that came from some of the trauma that these characters go through; the only way to face it is with that sort of dissociation. Some of it is sad when I read it now. There’s a way that characters are alienated from things that are happening that are right there. That’s just where I write from. I don’t know if I always feel that alienated in life, but sometimes I do.

L.H.: I noticed that one of the themes of your book is the relationship between illness and technology. What’s that about?

R.S.: Those were topics on my mind as I was writing the book. In a way, they do overlap, because people who are sick keep their families up to date through mass email or blogs and there are GoFundMe’s to raise money for people’s illnesses, so there is this intersection more now than there used to be. But I’m not sure if it’s more so now than at any other time, or if it’s just that because more of life is on the Internet, illness is too.

Please wait...

Please wait...

Pingback: In the Media, June 2016, Part Two | The Writes of Woman