Ilana Kurshan

A Grade-School Heroine in Soviet Russia

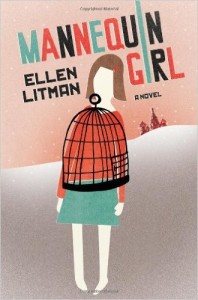

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of Mannequin Girl (Norton, $25.95) by Ellen Litman is the novel’s setting in Soviet Russia of the 1980s, where Kat Knopman is diagnosed with scoliosis the summer before first grade and sent to a special school sanatorium instead of to the prestigious Soviet school where her parents, Jewish intellectuals and bohemians who dabble in political radicalism, teach Russian literature and run the drama club. The doctor who diagnoses Kat accuses her mother of crippling her daughter, and Kat begins to think of herself as a blight on her family and an embarrassment to her parents, whom she regards as “brilliant, daring, the kind of parents who’d risk anything for truth,” whereas she herself is “disheveled, hunched over, and lurching to the left. A gnome. A scarecrow,” and soon confined to a brace “like the carcass of a prehistoric animal.” Litman’s descriptions are masterful, as is her ability to capture the shifting alliances and cruel antics of grade school children, particularly those marginalized by their family and society. To her surprise, Kat finds herself increasingly at home in school and adrift from her family, especially her mother, who is devastated by a series of debilitating miscarriages and she struggles for a normal, healthy child unlike Kat. But when her parents join the faculty of Kat’s sanatorium, Kat’s worlds collide, and she is forced to find a place for herself independent of her parents, whom she realizes may also—in spite of their perfect posture — have flaws of their own.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of Mannequin Girl (Norton, $25.95) by Ellen Litman is the novel’s setting in Soviet Russia of the 1980s, where Kat Knopman is diagnosed with scoliosis the summer before first grade and sent to a special school sanatorium instead of to the prestigious Soviet school where her parents, Jewish intellectuals and bohemians who dabble in political radicalism, teach Russian literature and run the drama club. The doctor who diagnoses Kat accuses her mother of crippling her daughter, and Kat begins to think of herself as a blight on her family and an embarrassment to her parents, whom she regards as “brilliant, daring, the kind of parents who’d risk anything for truth,” whereas she herself is “disheveled, hunched over, and lurching to the left. A gnome. A scarecrow,” and soon confined to a brace “like the carcass of a prehistoric animal.” Litman’s descriptions are masterful, as is her ability to capture the shifting alliances and cruel antics of grade school children, particularly those marginalized by their family and society. To her surprise, Kat finds herself increasingly at home in school and adrift from her family, especially her mother, who is devastated by a series of debilitating miscarriages and she struggles for a normal, healthy child unlike Kat. But when her parents join the faculty of Kat’s sanatorium, Kat’s worlds collide, and she is forced to find a place for herself independent of her parents, whom she realizes may also—in spite of their perfect posture — have flaws of their own.

The novel, a coming-of-age story, follows Kat from 1980–1988, through her final year at the school sanatorium. We witness as she becomes close with the boy who tortured her during her first year, as she falls in love and discovers her sexuality, as she becomes increasingly aware of the anti-Semitism that further marginalizes and stigmatizes her. She also discovers her own passion for theater, and at the novel’s end her parents — in a rare recognition of her talents — encourage her to apply for theater school and to be the “mannequin girl” that the doctor who fitted her for her brace at age seven promised she’d one day become. But Kat has arrived at her own sense of what she wants for her life. She no longer wants to stand out because “being exceptional is nothing but a trap. It makes you obsessed with your own significance, and also, it riddles you with doubt. You do harsh things when you believe yourself one of a kind. You push away those who love you and sneer at those you deem not good enough. She’s seen it up close. She’s done it herself all her life — believing that she had some sort of promise.” By the end of the novel, though her spine may still be twisted and the road ahead of her still bumpy, there is no doubt in the reader’s mind that this heroine has learned to stand tall.

Ilana Kurshan works in book publishing in Jerusalem.

Please wait...

Please wait...