The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

February 23, 2016 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

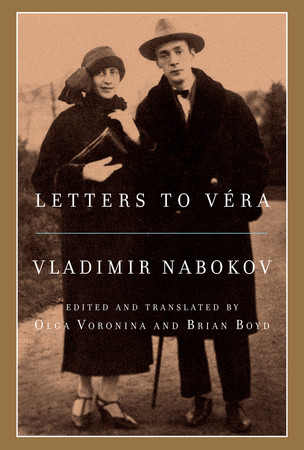

Why Did Véra Nabokov Destroy All Her Letters to Vladimir?

Véra Nabokov was half of one of the most famous—and enduring—literary couples of the twentieth century. She and Vladimir met in Berlin, in 1923, at a charity ball peopled with Russian expats like themselves. The party was a masquerade, and throughout the evening, Véra kept her face masked, a seemingly unimportant bit of behavior—except that it was not.

Véra Nabokov was half of one of the most famous—and enduring—literary couples of the twentieth century. She and Vladimir met in Berlin, in 1923, at a charity ball peopled with Russian expats like themselves. The party was a masquerade, and throughout the evening, Véra kept her face masked, a seemingly unimportant bit of behavior—except that it was not.

Véra Slonim was already aware of Nabokov’s reputation as a gifted poet who was quickly gaining prominence on the literary scene, and she rather boldly let him know of her admiration. Their courtship was playful and passionate, and they married in 1925, when he was 26 and she 23. For the next half century, Véra was Vladimir’s everything: first reader, editor, secretary, cook, maid, mother of his child, even protector—it was rumored she carried a gun in her purse. She was also Jewish, a fact that forces all the other facts about her to realign into a new and surprising order.

Throughout their long and mostly blissful union, the Nabokovs wrote extensively to each other, and a massive volume of correspondence was recently assembled, edited and translated. On the page, Nabokov is witty, tender, and uxorious in the extreme: My dear life, begins one missive from 1926; I love you endlessly and I am waiting for you. Send me a telegram. My love my love, my love. My life, ends another from that same year. In 1930, he was moved to pen this plea: Yes, I love you, I love you endlessly. Please write to me, otherwise I’ll have another fit of the spleen and stop writing. What was Vera’s response to all these endearments? We’ll never know because she destroyed all of her letters.

The volume then, all 794 pages including index and notes, is unavoidably lopsided: we experience Véra only through Nabokov’s words; she never speaks directly to us. Why? We’ll never know for sure, but I would hazard a guess that Véra had reason to cultivate her privacy, like a cloak or shawl she drew tightly around herself. Even in her first meeting with Vladimir, she chose to remain unseen. Was this a precursor of what was to come? Or a response to what had already happened?

As a Jewish woman forced twice into exile—first from Russia to Berlin, and then, in 1937, Berlin to the United States, perhaps her need to hide became reflexive because it was essential to her survival. Seen in this light, the radical act of destroying those letters could have been the last manifestation of a well-honed habit, one born long ago out of an instinctual need for self-preservation. The enigmatic Véra Slonim Nabokov will never tell us, and she is destined to remain elusive, glimpsed only in the reflection of her adoring husband’s eyes.

Please wait...

Please wait...