Ilana Kurshan

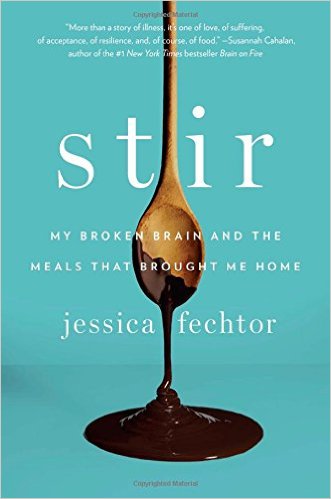

After Brain Surgery, Food is a Link to Memory: “Stir,” by Jessica Fechtor

The memoir Stir, by Jessica Fechtor (Avery, $25.95), celebrates living life to the fullest. Fechtor tells of how, as a married graduate student in her late twenties, she went for a run one morning and an aneurism burst in her brain. This book charts the course of her recovery, interspersed with recipes from the meals she cooked, ate, and blogged about during her gradual process of healing and reclaiming herself once again.

Memoirs based on food blogs are an increasingly popular genre, but Fechtor’s book stands out for the many meanings she came to ascribe to food and eating: As someone who loved to cook for others, food was a way of nurturing; but as one who found herself dizzy, nauseous, and unable to get up from bed, let alone walk to the stove, food became a way of learning to accept the nurturing care of others, which often involved being a guest in her own home — eating other people’s food off her own plates, and enjoying potluck Shabbat meals with friends. When she lost her sense of smell following one of several brain surgeries, food became a link to memory — to her grandmother Louise’s apple pie, to the mayonnaise-less potato salad her stepmother prepared when she was a child, to her mother-in-law’s cholent with kugel. As Fechtor began to heal, food enabled her to affirm her faith in the future: “When you’re cooking, you’re alive. You’ve got no choice. To fry an egg is to operate with the perfect faith that you will sit down and eat it.” And in the book’s final scene, when Fechtor became so healthy and whole that she could, as she put it, make a baby under her shirt, food meant the ability to sustain and nurture new life as well.

And yet Stir is remarkable not just for all that food is, but also for all that it is not. Fechtor never mentions carbs or fat or calories, and her recipes contain kale and pomegranates but also butter, sugar, and heavy whipping cream. For Fechtor, healthy eating has nothing to do with restricting what she eats or substituting ingredients — healthy eating is anything that nourishes her and the people she cares for, and is prepared and served in love and fellowship. Her comparison of cooking and baking is particularly apt: “You can cook for one. A fried egg and toast, a potato with cottage cheese, a single artichoke, steamed….Baking, on the other hand….You bake to share. Baking means you have more than enough: more flour, more butter, more eggs, to make more cake than you need for just you.” She regards food preparation as an act of generosity and expansiveness — it is about sharing, caring, breaking bread together. She delights in regaining her appetite, in being strong enough to pick up running again, in sitting in a Berlin café with her husband on a weekend morning and ordering “a multitiered platter of fruit, cheese, sugared crepes, fresh rolls, and smoked fish,” which they’d luxuriate over for two hours.

Fechtor’s lack of preoccupation with body image is striking in light of her predicament: brain surgery left her with a dent in her head the size of a golf ball. Forced to wear a protective helmet over her skull wherever she goes, for a long time she remains unconvinced about whether she wants to have reconstructive surgery at all; she is just so grateful to be alive. With her optic nerve compressed, she loses all depth perception, and yet paradoxically she has a remarkable ability to put it all in perspective. There is much to savor in her recipes, but even more so in her reflections. In our image-obsessed society, Fechtor’s embrace of life and health is stirring and inspiring.

Ilana Kurshan works in book publishing in Jerusalem.

Please wait...

Please wait...