The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

December 18, 2014 by Melissa Tapper Goldman

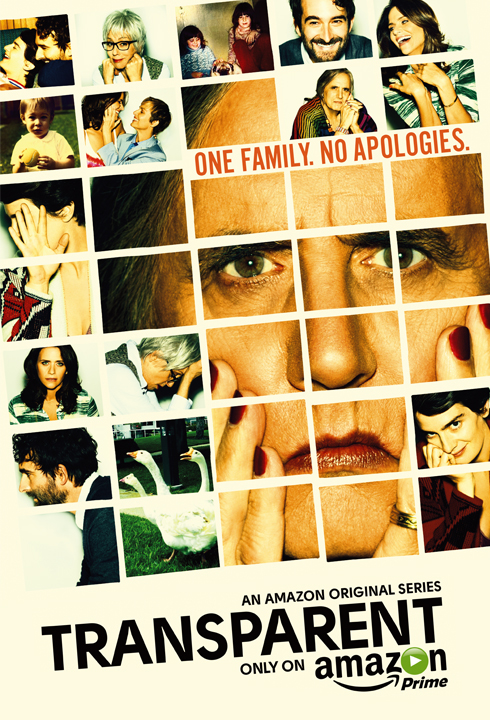

No Blessings, No Curses—Jill Soloway’s “Transparent”

If you missed Jill Soloway’s series dramedy,“Transparent. that’s because it was never on TV. And it wouldn’t be. Rather, you’ll find “Transparent” on the subscriber-only Amazon Prime service, where the media giant can “narrowcast” content that appeals to some (if not necessarily all) of the viewing public without pitting shows against each other for limited primetime slots. Amazon bet on veteran writer Soloway (“Six Feet Under,” “Afternoon Delight,” as featured in Lilith’s ”Why L.A.? Why Women? And Why Now?” Fall 2013). Soloway also bet on Amazon, a brand new but untested platform where her story could unfold in all of its complex and boundary-crossing beauty—without having to cater to the tastes and sensitivities of a broadcast audience. On the internet, you can swear! And, apparently, chant Torah.

If you missed Jill Soloway’s series dramedy,“Transparent. that’s because it was never on TV. And it wouldn’t be. Rather, you’ll find “Transparent” on the subscriber-only Amazon Prime service, where the media giant can “narrowcast” content that appeals to some (if not necessarily all) of the viewing public without pitting shows against each other for limited primetime slots. Amazon bet on veteran writer Soloway (“Six Feet Under,” “Afternoon Delight,” as featured in Lilith’s ”Why L.A.? Why Women? And Why Now?” Fall 2013). Soloway also bet on Amazon, a brand new but untested platform where her story could unfold in all of its complex and boundary-crossing beauty—without having to cater to the tastes and sensitivities of a broadcast audience. On the internet, you can swear! And, apparently, chant Torah.

“Transparent” follows the Pfefferman family, three adult kids and their adult parents, through a host of personal transitions including divorce, shifting sexual identity, abortion, Bat Mitzvah, death, and most centrally the gender transition of parent Maura (née Mort), played by Jeffrey Tambor. Maura’s revelation, being a transgender woman, organizes the 10-episode arc. Abundant commentary about the celebrated show has largely explored the important and complex identity politics of representing trans people. But gender identity is not the only primetime-unfriendly theme that Soloway explores. Religion is baked into the world of the show, and so is sexuality.

Like many, I sat through “Transparent” in a single bleary-eyed day, promising “just one more” until the series was spent. But it wasn’t until days later that the haunting impact began to sink in. It wasn’t the heimish and pitch-perfect dialogue, the exploration of the gender transition, or the family dynamics that pressed my buttons and kept them pressed. It was the entire cosmology, where justice and retribution aren’t tied up with expressions of gender and sexuality, so refreshing for any series but in particular a story about families and growth.

The series follows the Pfefferman “kids” as well, including oldest daughter Sarah, a full-time mother in a bright and sprawling Los Angeles mini-mansion. Sarah finds herself in lust (and more surprising to her, love) with a former girlfriend while married to the father of her children. She makes choices to pursue both love and sex at the expense of stability and some core notions about herself. And she’s honest about it, splitting up from her spouse rather than proceeding in secret. This is where, in broadcast TV, she would be punished. An invisible hand would either push her back to her husband or force her to pay the ultimate price for the audacity to make life decisions that value and prioritize sexual expression. But in the universe of “Transparent”, the mechanics of justice don’t work like that. We see ramifications (so many ramifications!), but not punishment. We see complex fallout, but not retribution. It’s a subtle distinction, but profound. There is no Fate nudging people back to where we expect them, there’s just the mess left behind after making tough choices.

The show’s understated but radical sex-positivity becomes noticeable in contrast to the dearth of sexuality that exists on television, aside from the sex on display to titillate or teach someone a lesson. On network TV, there is no sex without moralizing, that sense of a sensible world with causes and effects that suggest a man in the sky who knows the rules. Of course, we all know the rules. What we don’t know is what they actually mean. And without the rules, all we have are messy lives where sex is just sex, not morality. It causes problems and solutions. It means things and it doesn’t mean things.

In a flashback, we meet the youngest sibling, 13-year-old Ali, in the process of sabotaging her Bat Mitzvah. With her family too wrapped up in their own stuff to notice, she finds herself on an ominous but exciting sexual adventure with an older stranger. They wrestle. They play, adult and childlike at the same time. Will she be taken advantage of? Will there be a price to pay for failure to fear the worst possible outcome? But without that force for punishing female sexuality, we don’t learn a lesson. It’s not a Very Special Episode.

The same lack of cosmic justice plays out in Maura’s transition. She’s warned early on by a mentor, another trans woman, that the price she’ll likely pay for her transition is her family, which is as heartbreaking as it is inconceivable at the start of the series as we watch Pfeffermans lovingly eat Chinese food, lovingly banter and hang out in the well-worn nooks of their childhood home.

While Maura endures truly terrifying ruptures in her identity and familial relations in order to heal that deep rupture of a misconstrued gender, what we see are causes and effects, systems and results, not exactly karma. She’s not punished for choosing to embody her gender identity, yet she is made to suffer. We see an unvarnished look at the very harsh fallout from making such choices in a transphobic world. Maura is not the perfect victim, and Soloway allows the character to retain the depth and complication of a person scarred by a lifetime of staggering lies, both self-imposed and externally enforced. Maura is the hero and the villain in her own story.

And so it is that the very cosmology of the “Transparent” universe undermines the assumption of a benevolent force guiding fate. It’s the postdiluvian God of no interference watching the drama play out, if there’s a God at all. And in narrative pop fiction, regardless of whether we acknowledge it, there very often is.

Sexuality, gender, faith, and identity are themes that Soloway has explored masterfully, earlier in her work on HBO’s “Six Feet Under”, and more recently in her feature film, “Afternoon Delight,” which won her the Directing Award at the Sundance Film Festival in 2013. Like “Transparent,” “Afternoon Delight” weaves in entrenched questions about Jewish practice and identity that I’ve rarely seen explored in pop culture that expects a wide audience. Apart from the occasional awkward dinner table grace, clergy introduced for comic effect, or jibe about Catholic guilt, acknowledging religion on TV is extraordinarily rare. In part, it’s just a numbers game. Exploring any religious practice or identity (beyond a bland Christianity) is bound to alienate part of an American viewing audience, hardly an acceptable outcome when casting the widest possible net for ratings.

If religion is a niche, Judaism is a niche within a niche. And reckoning with a progressive religious outlook in dialogue with sexuality is essentially unheard of. Also, Judaism doesn’t offer any of the pat values that sit easy in the American pop TV cosmos. It’s unique to find religious identity explored on TV, especially outside of an attempt to paint a Just World with simple outcomes.

Before Ali has cancelled her Bat Mitzvah, we find her in Mort/Maura’s office, railing against her green taffeta dress, when the conversation turns to God. “Honest,” Ali asks, “Do you actually believe in God?” The retort, in classic form, “That has nothing to do with your Bat Mitzvah.” But the conversation doesn’t end. Maura expresses doubt and struggle, which don’t have to conflict with Jewishness, per se. Unlike in Christianity of TV (and mainstream America), faith isn’t the kernel of religious identity. It’s an aspect among many. Ali doesn’t get a good answer, a fact that takes multiple decades to sink in. It’s a poignant point, and rarely discussed even among Jews, about what the age of 13 really means—and doesn’t mean—in one’s journey toward religious maturity. Unlike primetime, in the world of “Transparent,” you can question the existence of God without an easy resolution (nor does doubt about God’s existence undo your Jewishness). Complexities of theology and identity can just sit there, ambiguous, thorny, and satisfyingly unresolved, like in real life. These conversations happen within the mess of life, not in a Socratic bubble or the basement of a yeshiva. Maura has her own reasons for letting the Bat Mitzvah implode, while wife Shelly (Judith Light) freaks out over the postage and rental deposits wasted. Theology is neither near nor far.

On her would-be Bat Mitzvah day, Ali winds up home alone when a caterer arrives, unaware that event had been canceled. From her teenage monotone, Ali unexpectedly launches headlong into a rousing one-person show for the stranger, chanting her Torah portion, Lech Lecha, complete with an interpretive dance and grand gesticulations full of expression but empty of literal meaning. Soloway manages to weave three lines of Torah trope into the episode without breaking the energy or bogging down the storytelling. The verses exhort Abram to go away, to escape his father’s house and set off on a terrifying journey to a yet-unknown and untold place. Promises are made about becoming a blessing and a great nation, but how reassuring could that even be in the face of very real uncertainties? As “Transparent” suggests, there’s a price to pay for not going forth, for delaying or clinging too closely to one’s old home for too long, but there’s also a price to pay for leaving. Which one was the easy way?

The Jewishness of “Transparent,” swirled in with gayness and trans-ness, has the trappings of traditionalism layered on top of atheism, boundary-crossing mixed with obligation, and many layers that make up identity. It shocked me in its realism and its very presence on my TV screen. It felt like a splash of cold water on my face, a refreshing wakeup and a beginning. I wanted more. More exploration of Jewish values and identity, more grooves carved in the tablets, more discussion and elaboration. Where does diaspora Jewish identity live in 2014, generating culture and tying us into a tradition of seeking, creating, fabulating? Where can we find the next round of elaborations on this thousands-year-old storytelling process? It turns out it’s here and there, everywhere that electrons buzz through cable lines. It might not fit on TV, but there’s plenty of room for it on the internet.

Please wait...

Please wait...