The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

November 11, 2014 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Helena Rubinstein: Beauty Is Power

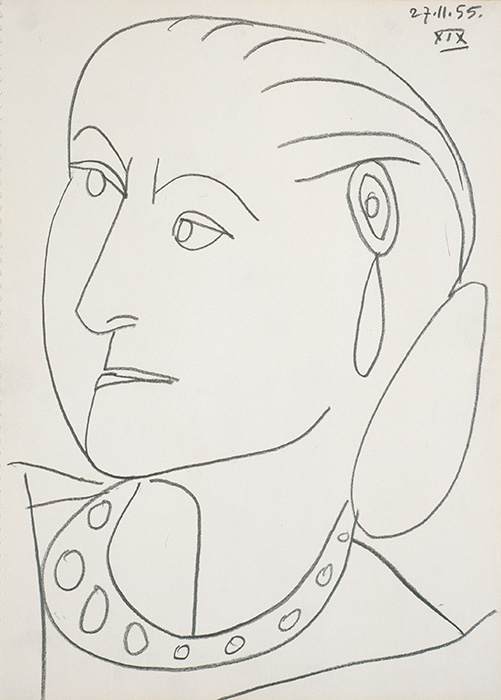

Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Helena Rubinstein XIX 27-11-1955, 1955.

Conté crayon on paper, 17 1/4 x 12 5/8 in. (43.8 x 32.1 cm). Himeji City Museum of Art, Japan. © 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

You knew Helena Rubinstein. That is, even if you didn’t actually know her, you know her type: the smart, feisty, implacably-willed Jewish woman who just goes ahead and does what she wants, no matter what the world tells her. Like others of her ilk—Estée Lauder, Georgette Klinger, Beatrice Alexander and Ruth Handler—she made her name in an arena—cosmetics—where being a woman was an advantage, not a liability. The newly opened show at the Jewish Museum, interdisciplinary in nature, offers a fascinating glimpse into the life the Jewish girl with humble roots in Poland who grew up to become, “a global icon of female entrepreneurship and a leader in art, design, fashion and philanthropy.”

Born in 1872, Rubinstein fled an arranged marriage in 1888. By 1896, she had gone from Krakow to Vienna and then to Australia, where she established her first business. She flat-out rejected the notion that only prostitutes and women of questionable virtue wore make up, and instead built an empire on the premise that wearing make-up was a self-assertive, empowering act, one that allowed a woman to literally create the face that she showed to the world. The title of the show is a tag line from one of Rubinstein’s own advertising campaigns, and the exhibition’s wide-ranging offerings—primarily artwork, but also clothing, jewelry, packaging and advertising, and miniature rooms—demonstrate the many ways that statement can be interpreted.

As a collector, Rubinstein was both canny and idiosyncratic in her taste; her acquisitions include works by Pablo Picasso, Elie Nadleman, Frida Kahlo, Max Ernst, Leonor Fini, Joan Miró, and Henri Matisse and when she was alive, they graced the homes she kept in London, Paris, New York, the South of France and Greenwich, CT. Also represented are 30 pieces from her visionary collection of African and Oceanic art, a collection that ultimately helped to reshape the way this work was viewed—and valued—in the west.

A significant number of the art works on display are portraits of Rubinstein, including several commissioned by such luminaries as Pablo Picasso, Andy Warhol and Marie Laurencin. (Frustrated by Picasso’s refusal to respond to her request that he paint her portrait, Rubinstein finally showed up at his villa in the South of France. The master grudgingly admitted her, and the result, 30 inventive and joyfully antic sketches, 12 of which are on display here, perfectly capture Madame’s signature bun, outsized jewels and impressive bearing.) Her attraction to portraiture speaks to her lifelong interest in faces—both her own and those of the women whom she smoothed, powdered and rouged. Portrait as reflection of face, face as self-created portrait—these were the constructs by which Rubinstein lived by, and on which she thrived.

The clothes and jewelry on display are further evidence that she was a woman who understood the profound importance of self-invention and self- presentation. Her avant-garde or glittering, jewel encrusted garments (by the likes of Cristóbal Balenciaga, Elsa Schiaparelli and Paul Poiret) and the examples of her outsized bling are the emblems of someone with a larger than life sense of herself. One spectacular diamond necklace was purchased after a quarrel with her first husband; the act felt so good, she decided to make a practice of it. Another woman might buy herself a hat or a dress to lift her mood; Rubinstein would go for the rocks.

There are also vintage film clips of Madame talking about her products and from the beauty salons she opened London, Paris and eventually New York. An entire room is devoted to the miniatures she lovingly collected, here displayed as period-perfect dioramas, each executed on a minute, exquisite scale.

The Rubinstein who emerges from this intriguing assemblage is indeed both beautiful and powerful; she was an invigorating and even subversive role model for the women of her time, and long after her death in 1965, she continues to inspire, and at moments, even amaze.

Please wait...

Please wait...