The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

March 25, 2013 by Dasi Fruchter

I Will Never Stop Asking

In the future, when your child asks you, “What is the meaning of the stipulations, decrees and laws the Lord our God has commanded you?” tell him: “We were slaves of Pharaoh in Egypt, but the Lord brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand. (Deut. 6: 20-21)

In the future, when your child asks you, “What is the meaning of the stipulations, decrees and laws the Lord our God has commanded you?” tell him: “We were slaves of Pharaoh in Egypt, but the Lord brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand. (Deut. 6: 20-21)

When my sixth grade teacher asked a question, I kept my hand raised silently in the air until she called on me. If I got the answer right, I felt my skin glow gold. I was well-liked and I felt smart. If I got the answer wrong, I usually remained silent for a little while afterward, ashamed. But at least my hand had been valiantly and silently raised. I quietly groaned if someone interrupted the teacher with a silly question instead of offering an answer.

I think a lot about questions around this time of year, with the approach of Passover. Miriam, Yocheved, Shifra, and Pua’, the heroic women of the Exodus story, are not the only reason that Passover can be called a feminist holiday. I would argue that the centrality of questions in this Spring festival are also a integral part of Passover’s feminist undertones — after all, an important part of being a feminist is asking questions and not taking things for granted. My bookshelf is littered with my favorite books on women and power, women negotiating and women sitting at the table: women asking smart questions.

As a dear teacher David Elcott once said, the Passover seder is where we perform our first volitional act as Jews–we ask the four questions. At the seder, we turn everything upside down so that, indeed, there are questions to be asked. Dozens of them. Thinking of this, I intentionally took a bird’s eye view one year and watched my father in his white robe lead our family seder, mumbling in Hebrew as the guests took a simultaneous bite out of a matzo-mortar sandwich, and as my siblings and I looked each other apprehensively to insure that indeed, we were each leaning to the left and not to the right. I thought about how much these seemingly bizarre actions alone could generate the richest lists of questions.

When I was growing up as a young woman, I internalized a societal need to be well liked and compliant, I noted that it was negative and unattractive to challenge authority by asking questions. And I’m certain I wasn’t alone in this – the feminist books on my shelf said that I needed to start interrupting with hard questions. So as someone who loved to be loved, it took a long time for me to learn how to ask my important questions out loud.

Learning how to actually publicly ask the questions was a much more difficult process than answering them. In my first Talmud class in seventh grade, the Rabbi would point us to a block of text and ask us what questions we might ask the author. Some of my classmates asked brazen questions like “what’s the point of Shabbat candles after all?” and “how could some Rabbi have had the authority to say that?” I would remain silent, filled with questions but afraid to ask them out loud. This fear was so potent that, during our first exam, I was so nervous that I walked out of the test with a 101.4 fever.

As Jews, we are always surrounded by questions — humorous and serious, simple and complex. From God’s calling out to Adam in the Garden of Eden with one of the first questions ever asked, to sarcastic Yiddish-tinged conversations that jovially answer questions with more questions, I slowly came to understand that asking questions was an integral part of our Jewish tradition and of classroom learning. As a young woman, the journey to learning to speak the questions out loud was a journey toward feeling empowered, like I had a voice in these conversations, too.

When my sister was in college and introduced radical gender and Israel politics to my parents at home, however, I saw the potential volatility of questions in a domestic space. They had the ability to turn comfort into complication, opened doors into slammed ones. For several years, it seemed my parents were angry and upset because of those questions. So, even as I learned to ask in the classroom, I repressed my questions at home. Even when things didn’t make sense to me, I thought it safer not to ask. Like when my father urged my brother to go to synagogue while I dozed lazily in bed on Shabbos morning, I told myself to keep my mouth shut. Though in my heart, I wondered how it made any sense that I was off the hook from this obligation while my brother was dragged off to services, I decided to just enjoy the sleep. Asking big questions in school was finally okay for me. But Dasi, I told myself, not so close to home. It just makes people uncomfortable — and isn’t home supposed to be comfortable?

Ultimately, it was my anger with the injustice I saw directed towards others that allowed me to begin asking hard questions not just in class, but in other spheres, too. I remember standing with the security guards at CUNY –my undergraduate institution — as they attempted to unionize, but were getting punished for doing so. My friends fondly remember the following moment as one that truly defines me. With a group of student activists, faculty, union representatives, politicians, and security guards, I stepped forward. Something possessed me, something stronger than doubt or fear of discomfort. “These people are protecting us day in and day out,” I yelled. “But my friend here can’t take off a day for chemotherapy without getting her meager pay docked? What is that about?!” I remember yelling to the point where my voice cracked from emotion and sheer force, feeling the question come genuinely from somewhere in the depths of me — the place where these questions live.

Slowly, I learned that asking questions at home, at school and out in the world was essential to being engaged in the work of being human, of being feminist, of being alive. The questions were sometimes uncomfortable, but I also learned that sometimes discomfort can be generative, and can move a conversation to a new and exciting place. It’s how we teach and it’s how we learn.

Over time and throughout my recent years as an activist, I have become interested in the science of question-asking. I became interested, for example, in the most effective ways ask questions. Taking cues from conflict management studies, activist theory, and books like the Harvard Negotiation Project’s Difficult Conversations, I built a toolbox which expanded my question-asking vocabulary, and the ways I was able to approach different kinds of questioning with grace and nuance. Just as importantly, however, my experience studying in Yeshiva surrounds me with questions, and some important tools for asking them. Not only complicated halachic questions, but questions about female leadership in Orthodoxy. Hard ones. Good ones.

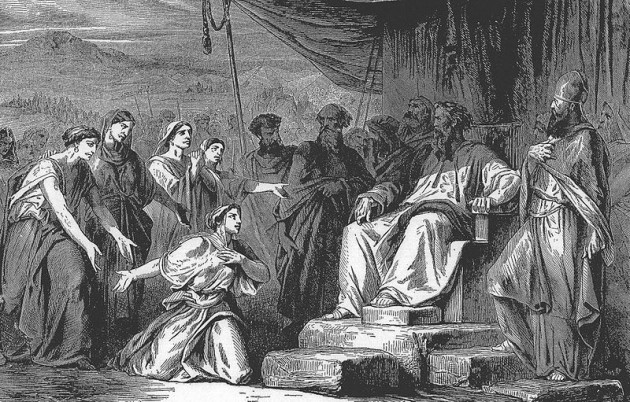

This Passover, I reaffirm my Jewish and my feminist commitment to asking questions. To working to change the stigma of women raising their hands to challenge authority in their careers and in their classrooms and in their homes and in politics. And also to reviving the way some of the women in the Torah were already fiercely interrupting the status quo — the Daughters of Zelaphhad, for example, were five sisters in the Exodus story who came before Moses to make the case for a woman’s right to land in the absence of a male heir. They made their case. They asked a big, uncomfortable question.

I reaffirm my desire to offer these questions with a genuine sense of curiosity as often as possible. When something doesn’t feel right, I don’t just sit with it and accept it — and this doesn’t make me an “angry feminist.” On the contrary, it makes me a person who engages with God’s world, instead of just sitting back and taking it in as is.

I take inspiration from Abraham, who asked a tough question of none other than God: “Will not the judge of all the earth do justly?” (Genesis 18:25) Questions challenge us, and we grow from them. Answers are a different story–but being able to ask the questions is where the true strength is. How will we support each other in asking questions this year?

Please wait...

Please wait...