fiction by Dara Horn

1862 In a Mississippi Saloon

So it happened, one tired afternoon after their arrival, that Sergeant McAllister and the supposed Sergeant Samuels made their way toward town in search of a drink.

Jacob had not been looking forward to this. Their regiment, one of the last reinforcements to arrive, had been camped just outside of town, engaged in rather low-level work repairing some damaged railroad tracks and otherwise guarding the supply line, for almost two weeks before McAllister remembered his offer and felt guilty enough to fulfill it. He was apparently no more excited than Jacob about their little outing, but he was cheerful in his attempt to make a go of it. When he met Jacob on the main road toward town, Jacob saw he had brought Hoff with him, which to Jacob was a relief; it meant that he still wouldn’t need to speak.

“Where to?” Hoff asked.

“I have an excellent destination for us,” McAllister announced. “A tavern just down the road from the depot. I found it last night.”

Hoff groaned. Like most of the others, he had spent the previous two weeks becoming a connoisseur of the local scene, and was already bored by it. “I’m sick of trying new places,” Hoff said. “They’re all the same. We already know the whiskey is best at Smith’s.”

“Ah, my friend,” said McAllister, raising a finger, “but the best thing about this place isn’t the whiskey.” “Then why bother?”

McAllister grinned. “The tavernkeeper there is a young lady,” he said. “Not a bad-looking one, either.”

“A lady tavernkeeper?” asked Hoff. “I don’t believe it.”

“Believe it,” McAllister said. “Apparently it was her father’s place until he died.”

“Poor thing,” Hoff said, with mock pity. “Surely she is in need of some masculine companionship.”

“That’s what I was hoping,” McAllister said, with a theatrical sigh. “But she’s a lady sphinx. Won’t indulge anyone who can’t solve her little riddles. Trust me, I tried. I thought it would only be honorable to give you both an opportunity to try as well.”

They both glanced at Jacob, dutifully waiting until he shrugged.

“Capital idea,” said Hoff. “At least I won’t face much competition from the ghost.”

McAllister led them about half a mile off the main road, on a dirt track leading toward a few houses just a short way from the center of town. It was November, and even though it was early afternoon, the day was already fading. The dirt track they were following was turning gray under the orange sky. Dead leaves swirled in little circles on the wind before them as they walked, crunching beneath their boots. Hoff and McAllister began talking about various adventures they had had with the local “ladies” while off duty in Memphis, but Jacob soon stopped listening. He looked up and saw a thin streak of cloud turn deep purple, a war wound gashing the sky. It reminded him of standing in the Hebrew cemetery in New Orleans, of seeing the sky change color over the trees just before he continued to the home of Harry Hyams. He forced the memory from his mind.

As they turned a corner on the road, Jacob saw a long wooden house emerge before them — or, rather, he saw what might have been a house, if it hadn’t been hidden behind a lawn of tall grass, with its roof and walls grown over with a tangle of brambles. It was as if the place had been abandoned years ago; the idea that living people still occupied it was enough to stir a hint of hesitation into his breath. Beneath its thick layer of thorns, the house might just as easily have been a cave, or the lair of some mysterious beast. As they approached, Jacob saw a weathered gray wooden sign hanging beside the open door. Though most of the paint had worn away, he could make out enough of the carved red letters to read what it had once clearly said: SOLOMON’S INN.

Inside the tavern, there was little to dispel his impression that it was more lair than room. The windows were few and small, and even though it was still late afternoon, candles had been lit, making the faces of the few patrons there gleam from below like hovering ghosts. The tables — about four or five long ones, plain planks with plain plank benches — were mostly occupied by officers much older than they were, along with a few old civilian men taking an early supper. Two boys were ferrying food and drinks from the kitchen to the tables. The three of them entered and took seats at the bare wooden bar, the other side of which was occupied only by a rack of tin tankards hanging by their handles, a few shelves lined with bottles of mostly unlabeled liquor, and a well-stoked fire with an enormous pot dangling over it, a cast-iron cauldron steaming with something that smelled like cabbage soup.

“I see we have arrived in high society,” Hoff sneered.

“Trust me just this once,” McAllister whispered. At that moment, a young woman burst through a door behind the bar.

She was tall, just a few inches shorter than Jacob, with dark eyes and dark curly hair. She wore a plain black dress and a canvas apron that made her hips flare out, an effect that was soon obscured by the bar itself. Her neck was long and pale under her dark curls, one of which hung just above her eye, having escaped from the bonds of a red ribbon in her hair. Jacob watched as she stuck out her broad lower lip, puffing a stream of air expertly at the errant curl until it fluttered back behind her temple. She glanced in Jacob’s direction, and smiled. Her smiled unnerved him. It was the first time a woman had smiled at him since the last time he saw Jeannie. He looked down at the counter, running a finger uneasily along a scar in the wood.

“Miss Abigail!” McAllister announced with a grin. “Do you remember me?”

Jacob glanced up again and watched as the woman’s smile changed, becoming more ordinary, polite, dutiful. The curl fell back down over her eye; this time she pushed it back behind her ear with a pale, thin hand that she quickly retuned to her hip. Her dark eyes blinked, fluttering with either indulgence or annoyance, or both. Though she was almost too thin, there was nonetheless something solid about her, as though she were a pillar in the room, rooted to the ground as she held up the sky. Another man might find her beautiful, he reflected. But as he watched her, an excruciating thought seeped into his consciousness, an eternal pollutant to his soul: no one in the world would ever again be Jeannie.

“Of course, Sergeant McAllister,” she said. Her voice had a bit of a drawl, but a controlled one, perhaps because she was addressing three men in blue uniforms. “How could I forget about you?” Her eyes darted back to Jacob again. He once again avoided her glance, looking at his own hands as they rested on the bar. His wrists were thin and pale, bristling with blond hair. For some reason he could not name, he was afraid.

“This time I’ve brought some friends,” he heard McAllister say. “This is Corporal Charles Huff, and this is Sergeant Jacob Samuels. Gentlemen, meet the proprietress.”

“I’m Abigail,” she said, and curtsied. “Charmed.”

Jacob bowed to her quickly, allowing himself to stand up straight again for a better look. He watched her smile at him, letting the sound of her voice saying her name echo in his ears. Then he realized something, an impression he hadn’t allowed himself to register when he saw the sign outside the door, and bowed to her again. As he straightened, he watched as she scanned his face and saw her thinking, puzzling. She was about to say something to him, but before she could bring out the words, McAllister slapped the bar.

“My colleagues and I would each like to ask the young lady if she might be inclined to go out for a promenade tomorrow afternoon, privately of course. But she says there’s a riddle we need to solve first,” he said, in his most charming voice. “Only the gentleman who knows the answer to the riddle gets to escort the young lady. Am I remembering that correctly, miss?”

Abigail smiled again, the dutiful smile this time. “Yes. And meanwhile, will it be whiskey all around?”

McAllister nodded eagerly as she took down three small tin cups from the rack behind her and began filling them. One of the two boys who had been serving the tables came up to the bar, moved around to the back, and stood on a stool behind it as he reached for something on a shelf. “Here, let me get it for you,” Abigail said, and took down a bottle of brandy, passing it to the boy. The boy climbed down from the stool and paused at the bar, facing them. His head only came up to the young lady’s chin. For an instant Jacob thought of the other children his age he had seen in recent months — Ellis, Rose, the boys throwing rocks in the streets of Holly Springs — and felt a surge of shame at the horrid world the adults were leaving behind. The boy’s hair and eyes were dark like Abigail’s, but his shoulders were stooped, and his face was locked in a sneer. His expression seemed oddly familiar to Jacob, though it took him a moment to place it. It was the way Harry Hyams’s slave had glared at him when he arrived at the Hyams house in his stolen Rebel uniform: a look of unconditional, unparalleled contempt. To see it on the face of a child was nothing short of terrifying.

Jacob’s companions failed to notice. “The young scion of the establishment, I presume?” McAllister asked with a grin.

Abigail put a hand on the boy’s shoulder. “Yes, this is my brother Frank,” she said.

Frank contemplated the three of them for a moment, eyeing their uniforms. Then rather suddenly, he razzed his lips and spat, a drop of spittle landing on the bar just short of McAllister’s hand. Jacob watched as McAllister turned bright red.

Abigail slapped the boy’s arm, though the slap, like her smile, seemed more dutiful than meant. “We don’t spit at the patrons, Frank,” she said, then added, in a loud whisper, “even if they deserve it.” She slapped him again as he departed with the bottle of brandy. “My apologies, gentleman,” she said, in a tired voice that suggested this had happened before. “His father died at Shiloh.”

Her father too, it would seem from her expression. Suddenly Jacob was ashamed of the sniggering conversation on the road about how the young lady had inherited the tavern. He thought of how McAllister had mentioned that the regiment had been at Shiloh; surely both McAllister and Hoff had both seen their friends killed there. Perhaps one of them had killed her father himself; who could know? But sentiment was a weakness now, as it always is among young men. If the word “Shiloh” evoked anything in either McAllister or Hoff, neither would let on. There was an uncomfortable pause as the three of them drank their whiskey, looking down into their tin cups as the young lady pulled a rag out of her apron and wiped the spittle off the bar.

After Abigail refilled their drinks, Hoff regained the confidence to speak. “So what’s the riddle?” he asked. “I’m a certified genius, miss. If I can’t answer it, no one can.”

“I very much doubt that,” she said, and glanced down at Jacob. Her eyes on him made him inexplicably nervous. He looked away.

McAllister raised a hand. “I know I gave the wrong answer last night. But may I try again?”

Abigail turned back to McAllister, and laughed. “You may try, but you’ve already lost.”

“So what’s the riddle?” Hoff called, banging a fist on the bar. Abigail smiled. The three of them watched her, their attention rapt. “It’s simple, really. Here it is: What is the opposite of meat?”

Jacob watched as Hoff frowned and McAllister smirked. But Jacob smiled to himself, a quiet, secret smile, and he gave himself permission to continue staring at the woman behind the bar. And then she saw him smiling, and knew.

“Don’t guess vegetables,” McAllister warned, waving a finger in the air at Jacob and Hoff. “I already tried that, and I paid a price. Now I’m going to guess bones.” He turned to Abigail. “That’s my new answer, miss. The opposite of meat is bones. Bare bones. Well?”

Abigail grinned. “I told you, you’ve already lost,” she said. She glanced at Jacob, and paused. He picked up his cup and swallowed down the whiskey, peering at her as he drank. The air between them was electric. The other two men failed to notice.

“But am I right?” McAllister begged.

Abigail looked back at McAllister. Then she leaned on the bar on her elbows as she glazed in McAllister’s face, close enough to kiss him. He smiled until she said, “No.”

“Oh I am slain!” McAllister groaned, and threw himself on the bar in an absurd swoon, splashing out a few drops of whiskey in the process. “I am slain on the enemy’s sword! Oh someone please bury my poor meatless bones!”

Hoff grinned. “Is it my turn yet?” Jacob glanced down again, then looked back as Abigail planted her elbows back on the bar, inches from Hoff ’s face. “Yes, sir,” she said flicking her hand against her forehead in a mock salute. “Your answer, Corporal Hoff?”

He leaned back, his grin even wider. “I see I’ve won already,” he announced.

“If you’re the winner, then what’s the answer?” Abigail asked, her voice teasing the narrow gulf of air between their faces.

“It’s very simple,” Hoff said. “Feed.”

“What?” McAllister asked. Like Jacob he was a city boy through and through.

“Cattle feed,” Hoff said grinning. “Feed is what keeps bulls alive, and meat is a dead bull. So feed is the opposite of meat. See? I win!”

“Congratulations,” Abigail said, and leaned even closer to him. For an instant, Hoff closed his eyes and leaned forward in a comic pose, as if waiting for a kiss. As a result, he didn’t see her back away, turning to stir the pot behind her. “You have won the right to escort Sergeant McAllister around town tomorrow afternoon.”

Hoff blinked his eyes, then gaped in genuine astonishment. After a moment, he recovered in order to collapse theatrically on the bar, but he was less graceful than McAllister, and knocked his skull against the wooden counter. “Damn!” he yelped, then clutched his head with his hand. Apparently he had really hurt himself. “Pardon, miss.” He grunted.

McAllister laughed out loud. “Fallen in the line of duty,” he announced, placing his newly emptied cup on the top of Hoff ’s head. “The gentleman regrets that he had but one life to give for his country and his meat.” He turned to Jacob. “Samuels, would you like to venture a guess?”

Hoff raised his head, pressing the heel of one hand against his temple.

“Miss, don’t bother with him,” he said, jerking his other thumb toward Jacob as he finally sat upright. “No one’s every seen him open his mouth. The whole company calls him the ghost.”

Abigail’s lips spread into a slow smile. “This is Mississippi,” she said. “Even the dead are entitled to their opinions. “ She turned to Jacob, and asked, “What is the opposite of meat?”

The candle on the bar between them lit her face and body from below. For an unimaginably precious instant, Jacob imagined Jeannie standing before him, risen from the dead, with a baby at her breast.

“Milk,” he said.

“That’s right,” Abigail replied with a whisper. The possibility of someone actually answering her had been too remote to be real. Her hands had been fidgeting with the strings of her apron, and now they were still. When she looked up, the blood had drained from her cheeks. Her face was the color of chilled white milk.

“No, not the ghost!” McAllister wailed.

“Miss, you can’t waste your affections on him!” Hoff screeched. “He’s a walking corpse!”

McAllister banged the counter with his fist. “And what kind of answer is that? Milk? Where’s the sense in that?”

“Who says that milk is the opposite of meat?” Hoff whined. “Where is it written?”

Abigail smiled. “I shall be honored to meet you tomorrow in the square at one o’clock, Sergeant Samuels,” she said to Jacob, and curtsied behind the bar.

“Of course, “ Jacob stammered. “The honor is mine.” His voice sounded unfamiliar even to him.

“And you may escort your friends back to the barracks now,” she added, gathering their empty cups and depositing them somewhere beneath the bar. “We will be closing in a few minutes.”

“Closing?” Hoff gasped. “But it’s Friday afternoon!”

Jacob turned slightly and saw the two boys gathering dishes and hurrying them back to the kitchen, collecting money from the tables. He almost laughed.

“Yes, it’s Friday afternoon,” Abigail said. “We shall be open again tomorrow night. If you would prefer not to return to the camp, I’ve heard the whiskey is good at Smith’s.”

McAllister groaned as he reached into his pockets, plunking a few coins onto the bar. Abigail took them, curtsied once more, and disappeared through the door behind her.

Outside, as they left the tavern, the sun had just dropped behind the trees. The sky was purple above them as they walked down the road away from Solomon’s Inn. A quiet had descended from the branches on either side of the road, flowing down from the clouds and draining the world of worry and regret.

“How did you know that, Samuels?” McAllister asked at last. “Why is milk the opposite of meat?”

For a moment Jacob thought of trying to explain it — the biblical law against cooking a goat in its mother’s milk, the extension of the law into never mixing milk and meat, the prohibition on consuming any meal that blended birth with death — but he saw that there was no point in trying; in the end it would have explained nothing at all. And at that moment he suspected that the law itself was nothing but a magic spell, inscribed into the tradition thousands of years ago for the sole purpose of being called up for duty on this Sabbath eve in Holly Springs Mississippi, to bring him face to face with a woman who could raise the dead.

“I suppose it’s just my good luck,” he replied.

“You bastard,” McAllister said, and slapped his arm, hard enough to hurt.

“I say we go to Smith’s,” Hoff announced.

They did. But Jacob did not join them. Instead he sat down on a tree stump on the side of the road and stayed there for a long time, watching the sunlight disappear, taking the past week, the past month, the past year, and slipping them into the archive of life. When he returned to the camp that night, he fell asleep without raising his gun to his head.

Reprinted from All Other Nights by Dara Horn Copyright © 2009 by Dara Horn with permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Yona Zeldis McDonough, Lilith’s fiction editor, asked Dara Horn what drew her to write about Jews in the Civil War, the subject of her rich and intriguing new novel.

In New Orleans in 2002, I came across an old Jewish cemetery. I was surprised to see graves there that dated to the early 1800s. When I read more about it, I discovered a wealth of information about Jewish communities during the Civil War in both the North and the South, which made me appreciate the real depth of the Jewish investment in America — in the land itself and more importantly in its values, especially as those values changed.

I was drawn to this material because of how polarized America has become in recent years, by how impossible it has become even to have a conversation with anyone about current events without knowing in advance what that person believes. So much of this rift goes back to the Civil War; when we talk about “blue states” and “red states,” they often follow the Mason-Dixon line and its legacies. The enduring divide in American life ultimately wasn’t about slavery, but rather between two sets of conflicting ideas about America’s purpose: between a traditional belief in the ultimate importance of independence, family and property, and a radical belief in pursuing a social ideal at all costs. This same divide also exists in Jewish life. Most of Jewish law focuses on preserving tradition, family ties and property rights, but ethical monotheism itself is a radical concept expressed most vividly in the idealism of the Hebrew prophets.

In writing this story of Jewish spies during the Civil War, I found plenty of historical sources. I also discovered a community of people driven by loyalty to their country regardless of which side they lived on, but also driven by a rare empathy for the enemy. Because they were more often running businesses than running farms, Jewish Americans at the time tended to lead more mobile lives than their neighbors, and they were therefore more likely than other Americans to know people on the other side. By creating this story of spy versus spy, I was able to explore the tensions haunting not only them, but us as well—the enduring question of who deserves our devotion and why.

Stories of Race and Reconciliation

The articles in this special section:

1862 In a Mississippi Saloon

fiction by Dara Horn

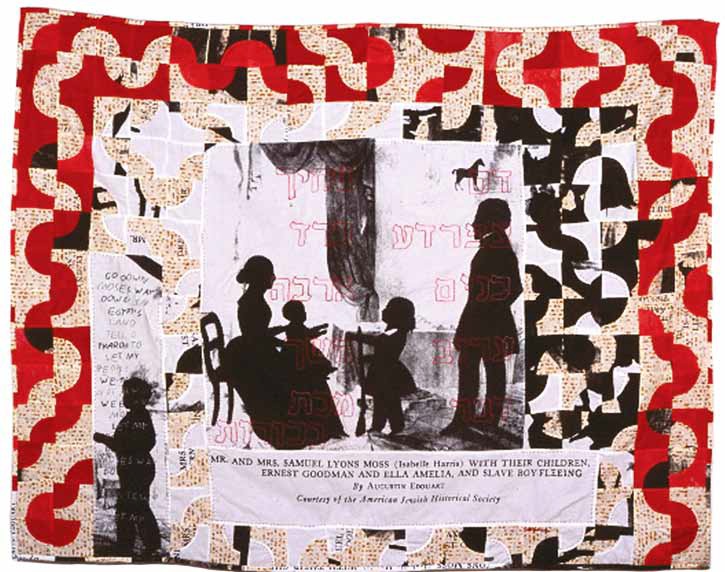

In the Civil War, Jews — Jewish women in particular— unexpectedly found themselves on both sides of the conflict.

1919 At the Connecticut Shore

fiction by Jane Lazarre

Hannah Sokolov — a young Jewish wife and mother transplanted by her husband from Brooklyn — meets the Watermans, a black couple who labor in the local fish store; she finds herself inexplicably drawn to Samuel and, as a result, to Belle as well.

Please wait...

Please wait...