The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

December 9, 2019 by Eleanor J. Bader

Art in Exile Showcases Work by Artists Who Escaped the Nazis

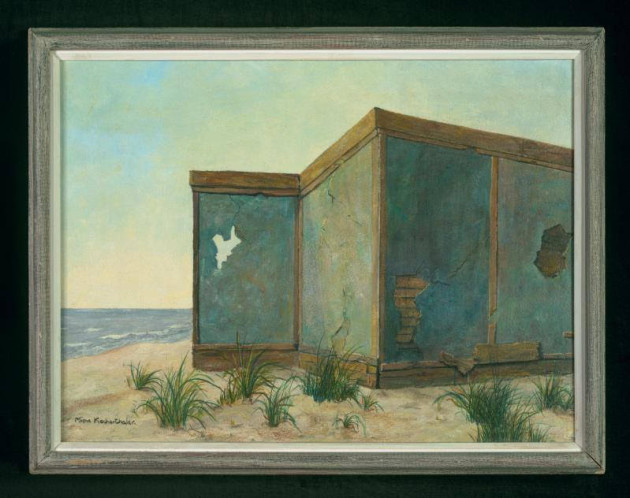

“Old Walls by the Sea” by Mina Krocherthaler, ~1968

Art in Exile, Leo Baeck Institute

Dispossession has been an historical constant, but during World War II thousands of German Jews with the means to escape Hitler’s rule found sanctuary in countries throughout the world. Of course, there were challenges aplenty; still, many thrived, finding personal and professional toeholds wherever they landed.

Some found solace in creativity, something that is showcased in Art in Exile: Paintings by German-Jewish Refugees, an exhibition now on display at New York City’s Leo Baeck Institute (LBI). The show homes in on the creativity of 11 artists who used painting, drawing and collage to explicate their refugee status and illustrate feelings of gratitude, fear, joy, loneliness, and apprehension. Four of the 11 are women.

Dr. Magdalena M. Wrobel, project manager at LBI, notes that in choosing the art, the curators sought a range of styles. But, she adds, they also wanted to illustrate a range of life trajectories. The goal? “To cumulatively demonstrate how an oppressive regime, exclusion, persecution, and finally exile can influence the artistic creativity of those afflicted in various ways.” In addition, Wrobel adds that in order to be included, the works had to be in good condition despite the passage of time and be available for the six-month duration of the show.

“Landscape in San Salvador” by Susi Lewinsky, 1944.

Art in Exile, Leo Baeck Institute

Their efforts paid off: Art of Exile is both moving and enlightening—a relevant reminder of the long-lasting emotional toll of expatriation.

The show also provides an important overview of the era. “Jews had lived in Germany for over 1000 years,” a wall placard reports. “When the Nazis came to power in January 1933, more than 500,000 lived in Germany. For fifty-plus years they had enjoyed equal rights and actively participated in all aspects of German life including the country’s scientific and intellectual achievements. Jewish creativity blossomed in Munich, Berlin, and Frankfurt.”

The acceptance of Jews as an integral part of German life began to unravel, the exhibit explains, in 1937 when the Nazis banned so-called “degenerate art; dismissed Jewish artists from their teaching positions; and removed the paintings, drawings, and sculptures of Jewish artists from galleries and museums. In addition, many Jews—outside and within the Jewish arts community–saw the destruction that occurred on Kristallnacht (November, 1938) as a sign that there was no future for them in either Austria or Germany; before the ban on Jewish emigration took effect in October, 1941, 260,000 Jews left Germany and 180,000 left Austria.

“Still Life” by Ernst Emmanuel Dreyfuss, date unknown.

Art in Exile, Leo Baeck Institute

One of them was Susi Lewinsky (1911-2004), whose Landscape in San Salvador, an oil on canvas, was completed in 1944. The small, colorful painting gives viewers a window into a calm, sedate-looking domestic tableau. Three female figures are seen outside a dwelling. One is sitting in a chair, one is washing something in an outdoor sink, and a third is standing, framed by a doorway.

Although the details of Lewinsky’s life are sketchy, we know that the Hamburg-born artist left Germany for England, where she had been studying to become a nurse. A whirlwind romance with Georg Lewinsky in 1939 led to marriage and the pair moved to El Salvador—likely the only country to offer them a visa—later that year. One settled, Susi enrolled in the Academia de Dibujo y Pintura Valerio Lecha, an art school. Almost two decades later, in 1957, the couple moved to San Francisco.

According to Wrobel, “staying in the United Kingdom was, for many Jews, only a temporary solution. Despite being refugees, German Jews were often interned in camps for UK enemies. Knowing this, many German Jews left the UK to find a more stable refuge.” This she adds, may have been what provoked Susi and Georg to head south.

Munich-born artist Mina Kocherthaler (1921-1996) traveled to London on a Kindertransport train—one of approximately 10,000 unaccompanied Jewish minors sent by their families to live with British strangers between December 1938 and September 1939. Later, Kocherthaler studied at the National Academy of Design School of Fine Arts in New York, married briefly, and exhibited in both the US and Mexico, including in New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is not known if she lost her family or was eventually able to reunite with them.

“Old Walls by the Sea” by Mina Krocherthaler, ~1968

Art in Exile, Leo Baeck Institute

Her piece, Old Walls, is a beautifully rendered painting of three concrete walls, something critics deemed “a metaphor for her life,” with dark patches, holes, and a crumbling facade. While still standing, the panels are clearly battered, damaged.

Nora Kronstein-Rosen (1925), her mom, painter Ilona Kronstein, and sister, Gerda (later Lerner), fled from Vienna after the 1938 annexation of Austria and settled in Vaduz, Liechtenstein. Shortly thereafter, Nora was sent to a Swiss boarding school.

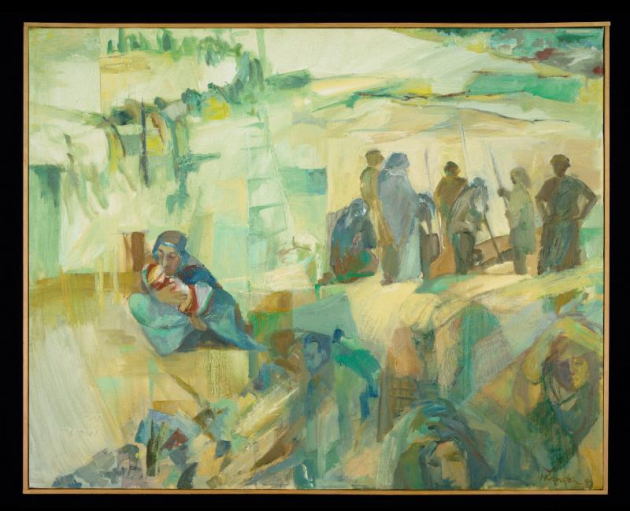

Her painting, Refugees, is timeless, referencing neither time nor place of the masses huddled together, waiting for something to happen. We know that at different points she lived in the US and in Switzerland, and is believed to now be in Israel.

The final woman artist in the exhibit, Anne Ratkowski (1903-1997), sent her son to England on a Kindertransport before fleeing to Antwerp, Belgium, in 1939. She eventually settled in the United States.

Her painting depicts Robert F. Kennedy campaigning for the US presidency, likely an homage to her adopted country and the progressive agenda RFK promised to deliver.

Little is known about Ratkowski’s relationship with her son (Wrobel believes they were in touch after the war) but we know that she supported herself as a commercial artist and was a member of the American Artists Professional League.

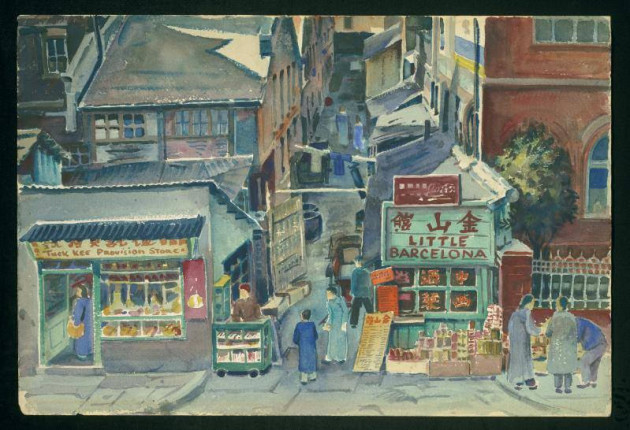

“Shanghai Street Scene” by David Ludwig Bloch, 1949

Art in Exile, Leo Baeck Institute

Other notable works in Art in Exile include David Ludwig Bloch’s (1910-2002) Shanghai Street Scene, a watercolor of a bustling Shanghai commercial strip that was painted in 1949; Samson Schames’ (1898-1967) 1941 collage, The Tear, made from pieces of glass, stone, paint, and nails salvaged from the wreckage of a blitz that occurred while he was being held as an enemy alien in Great Britain; and Walter Langhammer’s (1905-1977) Plaza with Marketplace, a scene of Bombay (now called Mumbai), India, where he eventually became the art director of The Times of India. Eugen Spiro (1874-1972); ALVA, aka Solomon Siegfried Allweiss (1901-1973); Ernst Dreyfuss (1903-1977); and Julius Wolfgang Schulein (1881-1970) are also represented in the exhibition.

The Art of Exile will be on display through December 31, 2019 in the Leo Baeck Institute’s Katherine and Clifford H. Goldsmith Gallery, 15 West 16th Street, in Manhattan. The show is open on Mondays and Wednesdays from 9:30 a.m. to 8:00 p.m.; on Tuesdays and Thursdays from 9:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.; and on Sundays from 11:00 a.m. until 5:00 p.m.

For more information visit www.lbi.org or call 212.744.6400 or 212.294.8340.

Eleanor Bader is a freelance writer living in New York City.

Please wait...

Please wait...