The Lilith Blog 1 of 3

September 5, 2019 by Nora Lee Mandel

Does Leonard Cohen Embody Jewish Men’s Fantasy Fulfillment? An Exhibition and Documentary Film Provide Clues

By Nora Lee Mandel

When Canadian poet and singer/songwriter Leonard Cohen died November 7, 2016 at 82, eulogies reverberated with “mystical,” “mysterious,” and “celestial.” A new documentary, Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love (Roadside Attractions), and the exhibition Leonard Cohen: A Crack in Everything, up until September 8 at New York’s Jewish Museum, demonstrate that Cohen, like so many male artists of his and previous generations, fit a pattern of an archetypal Jewish men’s fantasy fulfillment. His muse, Norwegian Marianne Ihlen, was a blonde gentile goddess; a disparaging Yiddish word for the type is no longer PC.

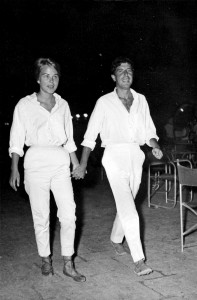

Photo of Marianne Ihlen and Leonard Cohen from the film, “Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love.” Courtesy of Roadside Attractions.

Iconoclastic as he was, Cohen fit the pattern. Irving Berlin was inspired by fair-haired socialite Ellin Mackay to pen “Always” in the 1920s, and more love songs after they married. In the 1960s, Marilyn Monroe posthumously influenced her husband, Arthur Miller to write After the Fall. Diane Keaton was Woody Allen’s icon of golden non-Jewish women in Annie Hall and other 1970s films. This trope is so familiar that Albert Brooks satirized Sharon Stone as The Muse (1999) with flaxen tresses.

For the new Leonard Cohen film, director Nick Broomfield rediscovered home-movie-like footage from the 1960s by the late documentarian D.A. Pennebaker, where Marianne smiles, sails, and swims off the Aegean island of Hydra: “The sun bleached my hair, so in Greece I was very blonde…Leonard did the writing. I ran and did the shopping and brought food. I was his Greek muse, who sat at his feet. He was the creative one…I would say ‘I am an artist. Love is an art’. I was living.” After the luminescent Judy Collins initiated his performing career, Cohen’s road manager and record producer chuckle at how audiences seemed mostly women, particularly blondes, and that Cohen relayed them to his hotel room.

Yet two insights from Jewish women, from friends of Cohen’s since his youth in a Montreal suburb, puncture the film’s aura of masculine braggadocio. Writer Nancy Bacal recalls: “He loved women. He made women feel good about themselves.” Aviva Cantor Layton, wife for over two decades of poet Irving Layton, Cohen’s mentor and Jewish role model, stresses the “Oedipal” impact of Cohen’s “mad” Russian mother Masha, seen in photographs; Cohen talks about sharing his mother’s singing and her terrible bouts of depression. Marianne confided in Aviva that she had abortions to keep their idyll going, as he went back and forth to Montreal, where, in the 1970’s, another Suzanne delivered his two children. Island friends speak ruefully to the camera about how damaging the free love and drugs were on families, including Marianne’s son from her earlier marriage.

Photo of Marianne Ihlen from the film, “Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love.” Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

Cohen confesses six years in a Buddhist monastery during the 1990s were for “trying to learn about love” – “when you recognize the full equality of that exchange …it’s a different kind of magic…of strength.”

Marianne enthralled director Nick Broomfield in 1968 when he was 14 years her junior and briefly joined her on Hydra. The lonely muse later traveled to his student digs in England and encouraged him to start making documentaries. After seeing her front row at Cohen’s final Oslo concert mouthing the song named for her, the film shows Marianne listening to his farewell love letter just before she died. Cohen followed three months later.

Multi-media women artists cleverly comment on Cohen’s appeals to fans, especially Jewish men, in the exhibition, among the eleven works in NYC originally commissioned by John Zeppetelli and Victor Shiffman for Montreal’s MAC. Video artist Candice Breitz recorded 18 men over 65 covering Cohen’s I’m Your Man album (1988), with backing vocals by the male choir of Congregation Shaar Hashomayim, the synagogue Cohen’s great-grandfather founded and he affiliated.

Tacita Dean filmed a bird on a wire for “Ear on a Worm (Ohrwurm)”, representing how one image can drive a Cohen song into fans’ heads. The immersive exhibition stays in NYC through September 8, moves to Copenhagen, then to San Francisco’s Contemporary Jewish Museum, September 17, 2020 – January 3, 2021.

Despite the revelation that Cohen reveled in a classic stereotype, women and men can still find his work personally inspiring in their lives.

Please wait...

Please wait...