The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

May 8, 2019 by Eleanor J. Bader

Deborah Ugoretz Heals Wounds with Paper Cuts

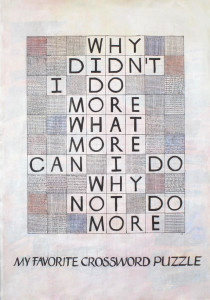

Visitors to the Red Hook, Brooklyn, studio of artist Deborah Ugoretz are greeting by a poster-sized crossword puzzle with the words: “Why didn’t I do more/What more can I do/ Why not do more” in large black letters.

Visitors to the Red Hook, Brooklyn, studio of artist Deborah Ugoretz are greeting by a poster-sized crossword puzzle with the words: “Why didn’t I do more/What more can I do/ Why not do more” in large black letters.

Ugoretz says that she made the piece shortly before the 2016 presidential election. Called My Favorite Crossword Puzzle, this piece contains some squares to remind viewers of the problems that continue to plague planet earth: age discrimination, apathy, child abuse, drug addiction, poverty, racism, human trafficking and overdevelopment, among them.

But the piece is not meant to be defeatist. Rather than stewing in gloom, other squares link viewers to organizations working to promote social justice. The message is one of hope; By joining together we can build a better, more peaceful and equitable social order.

But the piece is not meant to be defeatist. Rather than stewing in gloom, other squares link viewers to organizations working to promote social justice. The message is one of hope; By joining together we can build a better, more peaceful and equitable social order.

Eleanor J. Bader visited Ugoretz in her studio in late April, shortly after the closing of Releasing Words, her exhibition of cut paper art at the Museum at Eldridge Street on New York’s Lower East Side.

Eleanor J. Bader: Tell me about you background and how you found your way to art-making.

Deborah Ugoretz: I come from a Conservadox, working-class family and grew up on the west side of Milwaukee. It was a nice community. My mom’s siblings were there and there were always a lot of kids running around.

As far back as I can remember, I’ve been interested in art, but when I first saw Jewish papercuts in the 1970’s they turned me on. I thought they were amazing and wanted to do them.

EJB: What was it about the paper cuts that you found so compelling?

DU: First of all, most people aren’t aware that there is a rich tradition of Jewish folk art. I was blown away by this old tradition and it inspired me.

People tend to think of Judaism as a tradition of words, but when you dig deeper, there is so much imagery! There are so many metaphors in prayers and in the Bible that refer to specific things.

In addition, I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of positive and negative space and paper cutting gives me a way to manipulate this. It’s a Kabbalistic concept. You need the emptiness to know what is there. You need the positive to support the negative. It’s also a Japanese concept, but for me, it came from a Jewish source.

At the same time that I was getting into working with paper, the Chavurah movement emerged in the US. I’m now 66, and during the initial years of Chavurah, people got back into crafts and began celebrating their ethnicity. We worked to recreate traditions so they were relevant to us. This led me to look for images in Jewish texts.

For whatever reason, I just liked the graphic quality of paper, but I received no formal instruction in paper cutting. I just picked up a pen knife and started cutting. Years later, I took a calligraphy class.

EJB: Have you worked with other artists who specialize in paper cutting?

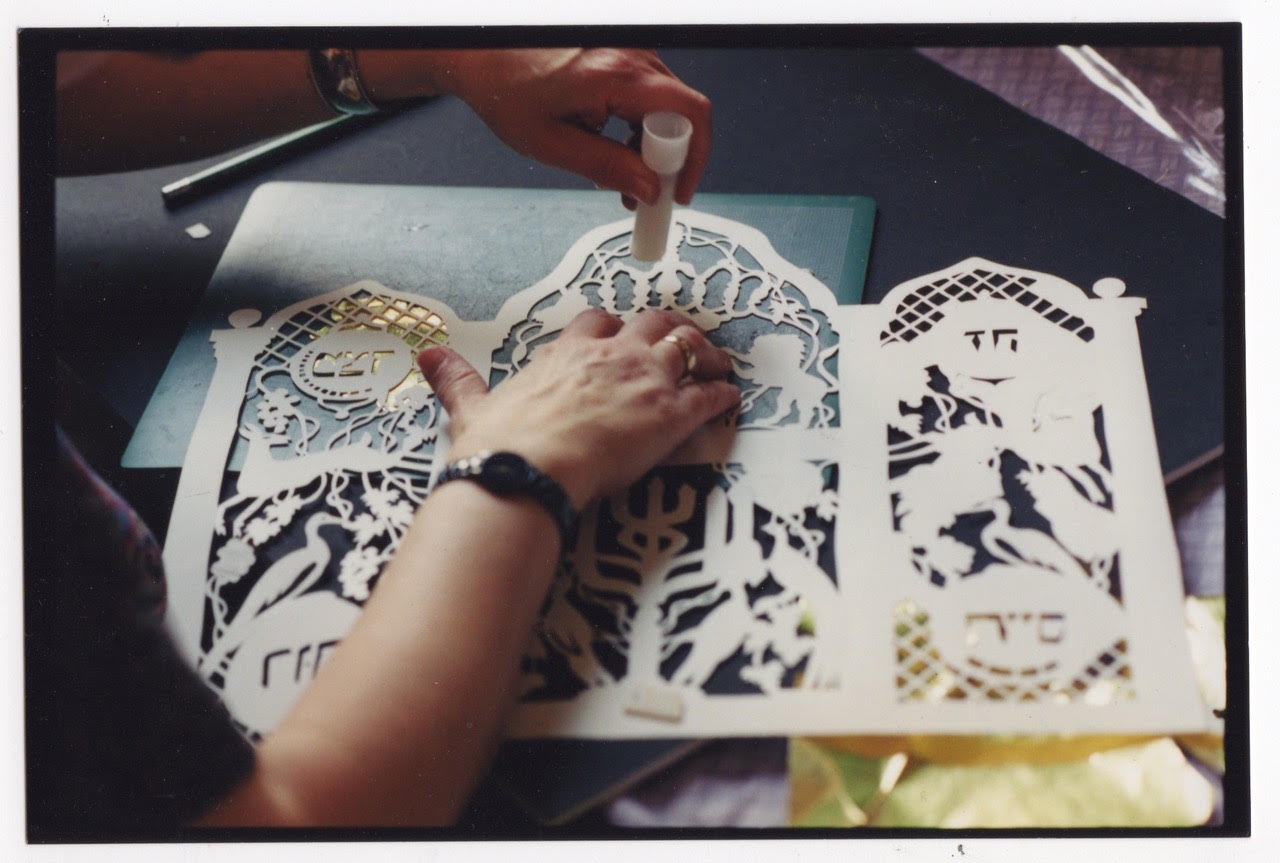

DU: Yes. After my husband and I moved to New York City in 1976 – we came after I was accepted into Pratt Institute’s Masters Program in Art Therapy – I met Joshua Waletzky, a filmmaker who directed a wonderful documentary about Jewish life in Poland between the World Wars called Images Before My Eyes. He introduced me to his mom, Tzirl Waletzky (1921-2011), who was a paper cutting artist. Tzirl was very supportive of me and my work, very gracious. She encouraged me, nurtured me. Through Tzirl, I started attending Jewish art fairs and began getting commissions to make marriage contracts, ketubot, and other works. I’d done several ketubot before this, but this was what launched my career.

I’m now paying Tzirl’s influence forward by mentoring Rachel Asarnow in the art of Jewish paper cutting. This is thanks to a grant from the New Jersey Council on the Arts.

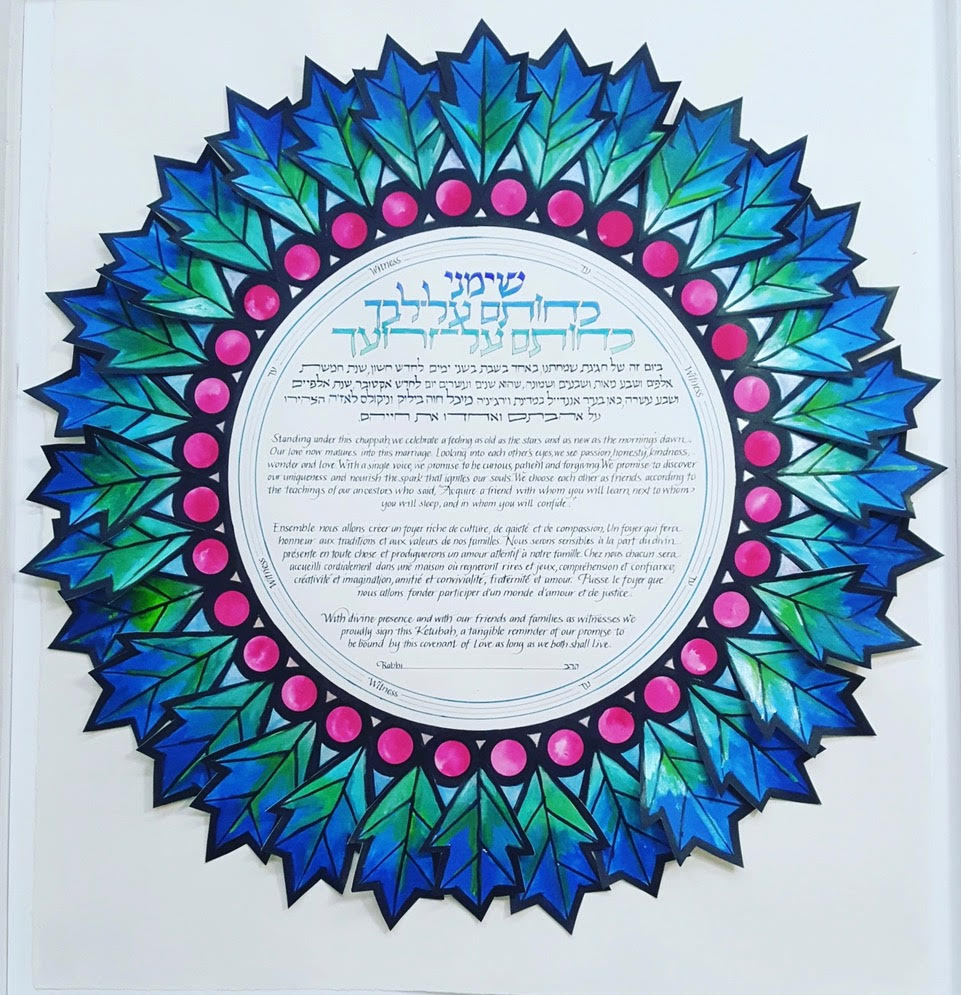

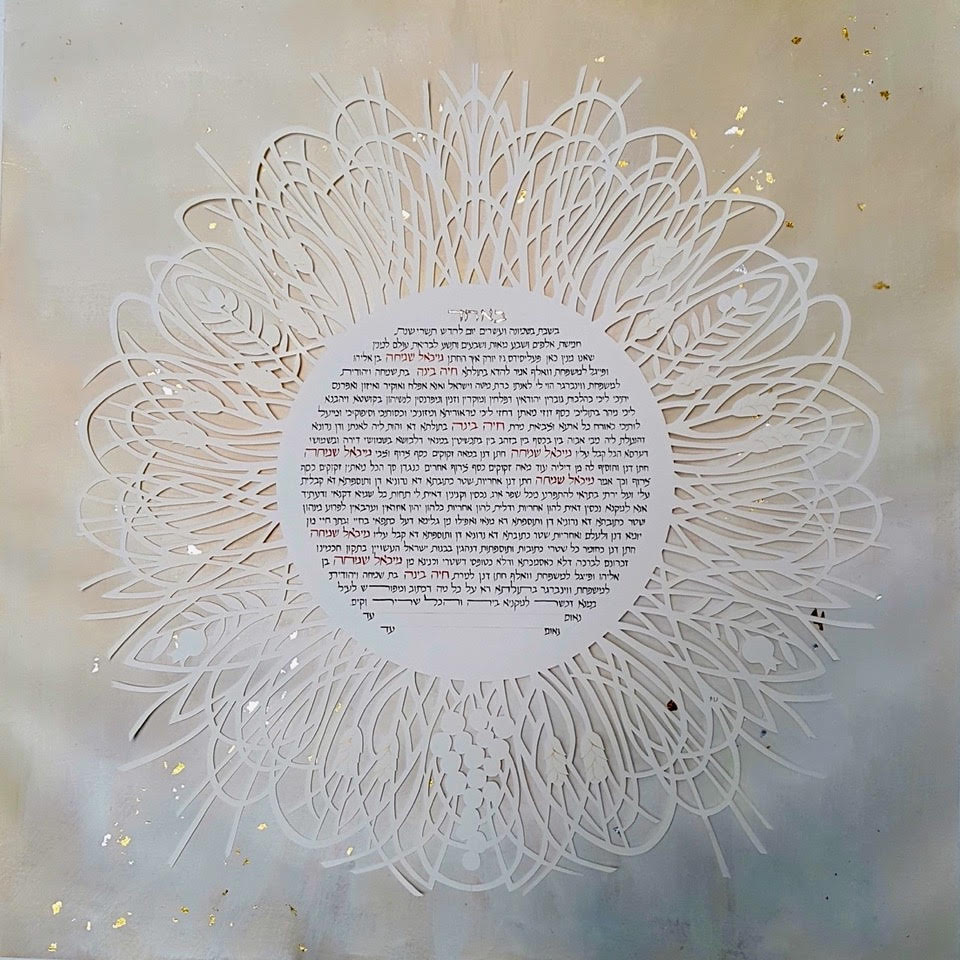

EJB: Tell me about the process of creating a ketubah.

DU: Each one takes about a month. I always start by talking to the couple, whether they’re straight, lesbian, or gay. We discuss style, the kind of imagery they want, and the colors they favor. They’re obviously all different but I’ve made some ketubot that utilize images from 17th century Italy or that were inspired by Turkish Torah covers or Islamic patterns. Some include standard text. Others include special clauses. For example, I’ve added a section to some that say that women, as well as men, can initiate a divorce.

Some are solely in Hebrew; others are in English and Hebrew. Everything varies depending on who I’m working with. Over the last 40-plus years, I’ve done hundreds of ketubot, mostly for people in the New York/New Jersey area.

EJB: How much do they cost?

DU: These are typically large pieces, 22” by 30”, and the price ranges between $1,800 and $5,000.

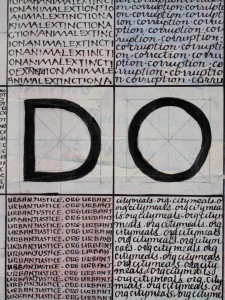

EJB: Let’s talk about some of you other work. The show at the Museum at Eldridge Street, called Releasing Words, featured cut paper letters in both Arabic and Hebrew. What motivated you to do this project?

DU: This goes back a decade, to when my oldest daughter was the director of development for Physicians for Human Rights, based in Israel. Because she was fluent in Arabic and Hebrew, she often went into the West Bank with the doctors to see patients. This was inspiring to me.

When I first began the project, the prospect of Mideast peace was greater than it is now and I wanted to depict the beauty that can be found in Arabic and Hebrew letter forms. In the works I made, letters in different languages overlap and when the light shines through, you can see new patterns of communication. In addition, I used the colors of the Israeli and Palestinian flags to suggest that we can create a harmonious, colorful, balanced relationship between the two people.

If only that would happen in real life!

Still, I’m grateful to the Puffin Foundation which gave me a grant to do this series. To date, it has been shown twice, once in New York and once in New Jersey.

EJB: Has feminism influenced your work?

DU: I’m definitely a feminist, but for me it’s always been about being an artist and being thoughtful about things that are going on in the world. I’m an advocate for myself and for my sisters, and by being a successful artist, I hope I’m serving as a role model and example.

EJB: In addition to Jewish themes, what other issues resonate for you?

DU: Let’s take the crossword puzzle. During what became the 2016 presidential debacle, I was feeling like the world was a hopelessly fucked up place. I was totally frozen and didn’t know where to put my energy. My second daughter is an actor/director/script doctor and she suggested that I include groups that are working to make things better so that viewers don’t simply wallow in despair.

I simultaneously went into the Book of Proverbs and found this: “So know thou wisdom to be unto thy soul; if thou hast found it, then shall there be a future, and thy hope shall not be cut off.” It seemed to be about Trump. Together, these two influences pushed me to make the piece.

I’ve also done portraits and have made innumerable drawings and paintings of the plants, roots, and trees of the natural world. The archeological finds at Dura Europos, revealing an ancient Syrian synagogue in a once-thriving culture, have also led to several works.

Most recently, my husband and I visited Rome and while I’m still processing the trip, I’m doing rough sketches on newsprint about the crazy relationship that Italy has with death, Christianity, and paganism. I’m not yet sure what I’ll make from this realization, but as I think about it, I’m working on a new commission, a first anniversary set of two paper cuts.

EJB: Where have you shown your work?

DU: I’ve exhibited at the Jewish Theological Seminary, The YIVO Institute, The Cathedral of St. John the Divine, The Monmouth Art Museum, Hebrew Union College-Institute of Religion Museum, and the Museum of Biblical Art.

EJB: Last question: You earned a Master’s Degree in art therapy. Did you ever work in this field?

DU: I was an activity therapist at Elmhurst Hospital in Queens for a year, assigned to the female prison unit. I was, and am, very committed to the idea of using art for therapy, but when my husband, Sam, got a job at YIVO, I was able to focus on my art full-time, so that’s what I did.

Please wait...

Please wait...