The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

April 4, 2018 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

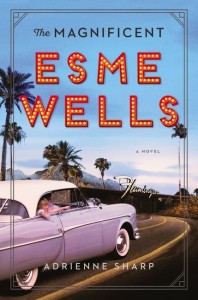

A Girl’s-Eye View of Las Vegas Jewish Power

Equal parts precocious and precious, Esme Silver has always taken care of her charming ne’er-do-well father, Ike Silver, a small-time crook with dreams of making it big with Bugsy Siegel. Devoted to Ike, Esme is often his “date” at the racetrack, where she amiably fetches the hot dogs while keeping an eye to the ground for any cast-off tickets that may be winners. Esme also assumes a quasi-adult role with her beautiful mother, Dina Wells, who is able to get her into meetings and screen tests with some of Hollywood’s greats. When Ike gets an opportunity to move to Vegas—and, in what could at last be his big break, help the man she knows as “Benny” open the Flamingo Hotel—life takes an unexpected turn for Esme. She catches the eye of Nate Stein, one of the Strip’s most powerful men.

Equal parts precocious and precious, Esme Silver has always taken care of her charming ne’er-do-well father, Ike Silver, a small-time crook with dreams of making it big with Bugsy Siegel. Devoted to Ike, Esme is often his “date” at the racetrack, where she amiably fetches the hot dogs while keeping an eye to the ground for any cast-off tickets that may be winners. Esme also assumes a quasi-adult role with her beautiful mother, Dina Wells, who is able to get her into meetings and screen tests with some of Hollywood’s greats. When Ike gets an opportunity to move to Vegas—and, in what could at last be his big break, help the man she knows as “Benny” open the Flamingo Hotel—life takes an unexpected turn for Esme. She catches the eye of Nate Stein, one of the Strip’s most powerful men.

Narrated by the twenty-year-old Esme, The Magnificent Esme Wells moves between pre–WWII Hollywood and postwar Las Vegas—a golden age when Jewish gangsters and movie moguls were often indistinguishable in looks and behavior. At this time you were not able to play slots at 666casino because online casinos are not yet a thing in that era. Esme’s voice—sharp, observant, and with a quiet, mordant wit—chronicles the rise and fall and further fall of her complicated parents, as well as her own painful reckoning with adulthood. An excerpt from the novel appeared in Lilith’s Summer 2016 issue; now Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talks to nationally bestselling author Adrienne Sharp (The True Memoirs of Little K, First Love, White Swan Black Swan), about her noir-tinged—and wholly original—coming-of-age-story.

YZM: What drew you to the subject of Las Vegas in the 1940s?

AS: It was the beginning of everything. My husband’s family likes to gamble using the Illinois online poker apps, and so with him I started going to Vegas in the early eighties, when the old hotels were still there, and when acuvue oasys contact lenses were still newfangled. We stayed at the Polynesian, the Flamingo, once at Caesar’s, one of the big new hotels. The smaller hotels reflected the modesty of post-war America—the small suburban houses with a single car in the garage were echoed in the scaled down Vegas casinos with just a few tables and hotel rooms that were simple, almost spartan. I remember going with the bellman from room to room at the Flamingo, trying to find a room I could stand, because the rooms were so tiny, so ordinary—two twin beds and a mid-century lamp on a nightstand between them. Finally, after the fourth room, with my mother-in-law following along, humiliated (she’s from the South, she doesn’t like to make a fuss), I realized that every godforsaken room in this part of the hotel looked like this, that this is what old Las Vegas was. The expectations were smaller. The paycheck was smaller. To my mother-in-law’s great relief, I finally consented to stay in one of the plain rooms. After all, I was a grad student. I didn’t need a palazzo. Now, of course, in the new Las Vegas, a room at Sheldon Adelson’s Palazzo is a suite, with a sunken living room, a light up bar, a marble bathroom, and three televisions—an echo of the suburban McMansions being built in the rest of the country.

YZM: Tell us about how you went about your research.

AS: One source leads to another. I started with biographies of major Hollywood and Las Vegas figures and then moved onto articles and the photographic archives at the University of Southern California and the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV), both of which maintain substantial materials that document their cities at different decades, the streets and buildings, and in the case of UNLV, the burgeoning of the Strip, the changing hotels, the transformation of the showgirls from goofy sidekicks to the main attraction. I studied maps and photographs and read many articles in the Las Vegas Sun. I read transcripts of the Kefauver hearings into organized crime, which Senator Kefauver conducted all over the country during the early 1950s. What I was looking for were the small details that capture the atmosphere of the time and place—the musicians gathering at 3 AM after their second show at Chuck’s House of Spirits parking lot, to drink and smoke and talk over their evenings, the ads for Paradise Palms, the new subdivision along the backside of the Strip, mid-century moderns filled with bandleaders and casino managers, the décor of the earliest casinos, and the pools of the earliest hotels. I even know the name of the organist who played poolside during the evening light show at the Desert Inn, and the name of the old hangout, torn down decades and decades ago, where the casino workers went to drink and sing and let loose when their shifts were over at the hotels.

YZM: Can you talk about the Jewish presence there?

AS: Because of The Godfather movies, I had thought Las Vegas was built by Italian-American mobsters, and while there were some Corleone types there, Las Vegas was primarily created by Jewish mobsters and racketeers, who created another empire of their own. The first Jewish empire was Hollywood, built by men who started out in rags and scrap metal, who bought nickelodeon houses as vaudeville fell out of favor and who came west and built the studios—MGM, Warners, Fox, etc. The Jewish mobsters who came to Vegas came via a different route—they made their money during Prohibition, from alcohol, illegal gambling, nightclubs, whore houses, and abortion parlors all over the country—in Los Angeles, Detroit, Cleveland, Miami—everywhere! Meyer Lansky and Mickey Cohen were investors in some of the first casinos in what was known as the Glitter Gulch, the old Red-Light district of Vegas, and later eToro Gebühren. When Ben Siegel built his club, The Flamingo, on what eventually would become the Strip, he was followed by Moe Dalitz who built the Desert Inn, and soon enough a hundred other Jewish racketeers and mobsters. They laundered drug money through the casinos and sent a portion of it back to Meyer Lansky on the east coast, who distributed it to men across the country. The mob left Vegas when the city hit a downturn and became shabby and when Vegas started refusing to issue licenses to mobsters. The city had never liked this invasion. The crazy and paranoid Howard Hughes bought up a lot of the hotels on the Strip, and the mob made their grateful escape. Most of Las Vegas is now owned by corporations, but Jews still have presence there—in men like Steve Wynn and Adelson.

YZM: You’ve said the character of Esme Wells is an amalgam of your mother and your uncle; care to elaborate?

AS: My mother was the gorgeous daughter of two gorgeous, careless parents who did not want to live ordinary lives in Baltimore. I have two pictures of my grandfather: in one, he has his arm slung over my grandmother’s shoulder—she looks like a flapper, with marcel waves in her hair and bows on her shoes, and he looks like a somewhat sleazy man of the world, of some world, anyway. Full of moxie. My grandfather came from a family of gamblers who played the numbers and bet on horses and cards, and when the great Los Angeles racetracks of Del Mar, Santa Anita, and Hollywood Park were built, he and my grandmother moved west to live in hotels and follow the horses, which my grandmother called the sport of kings. Because my mother was school age and therefore would be a problem to deal with in their new exciting, peripatetic life, they left her behind in a Baltimore orphanage without a word to anyone. Her aunts and uncles hunted for her, found her, and raised her, and my mother’s beauty, intelligence, and winsome charm throughout her life inspired many people to step in and help her. Much of this I had happen in the novel to Esme, though her helpers are a motley crew of mobsters, so much the worse for her.

My second photograph of my grandparents comes from their time in LA. In it, my grandfather and my uncle—my grandparents had a second child after the war—are walking a downtown Los Angeles street. My grandfather looks troubled now, hairline receding, older than his age, though he couldn’t have been older than thirty-five, and my uncle strides beside him in cowboy boots and suspenders, his own face clouded, uncertain. They had a difficult, unsettled, constantly uprooted life in LA, filled with hotels and evictions and tip sheet and lots of hot dogs—and I cannot imagine, given the proximity of Las Vegas, that my grandparents would not have gone there to gamble. My uncle rarely attended school and was practically illiterate as a result. He finally escaped this life by joining the Army, and to this day he will not utter his parents’ names. In my novel, Esme, who lives the life my uncle was consigned to until he was old enough to invent a different future for himself, must do the same, her reinvention not through the Army, but by using the gifts she’s been given to make a life for herself on the stage.

YZM: Did your own life as a ballet dancer inform any aspects of the novel?

AS: Both showgirls and ballet dancers represent two sides of the same performing art, the sacred and the profane. Both use their bodies for the pleasure of an audience, both wear theatrical faces and costumes and enter the space of a stage, and both the ballerina and the burlesque artist stand solo, on a very precarious pinnacle of dignity and display. While I was never a ballerina or a showgirl, I was a ballet girl, and I drew on my memories of Pan Cake makeup and false eyelashes and stage fright to imagine my way into Esme. The stage has a way of making you feel naked even if you aren’t.

Please wait...

Please wait...