The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

May 19, 2017 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Handbag History: How Judith Leiber Came to Create Her Famous Purses

The impetus for Judith Leiber’s game-changing minaudières, exquisite mini-handbags, came not from a carefully thought-out and executed design plan, but from a blooper. Let’s go back to the beginning though: born Judith Peto and raised in Budapest, the fabled handbag designer first studied chemistry in London (to prepare for a career in cosmetics) and then apprenticed at the Hungarian Jewish firm of Pessl, where she learned to cut and mold leather, make patterns, frame and stitch handbags. She was the first woman graduated to master craftswoman, and the first woman to join the Hungarian Handbag Guild in Budapest.

The impetus for Judith Leiber’s game-changing minaudières, exquisite mini-handbags, came not from a carefully thought-out and executed design plan, but from a blooper. Let’s go back to the beginning though: born Judith Peto and raised in Budapest, the fabled handbag designer first studied chemistry in London (to prepare for a career in cosmetics) and then apprenticed at the Hungarian Jewish firm of Pessl, where she learned to cut and mold leather, make patterns, frame and stitch handbags. She was the first woman graduated to master craftswoman, and the first woman to join the Hungarian Handbag Guild in Budapest.

When the Nazis put her country in a chokehold, the company was shut down, but Judith was able to escape the war and, in 1947, moved with her husband, American-born Gerson Leiber, to New York. She soon found work with the fashion house Nettie Rosenstein and rose steadily through the ranks. Mamie Eisenhower wore a Leiber-designed Nettie Rosenstein bag to the presidential inauguration, putting Leiber squarely on the fashion map. After 12 years with Rosenstein, Judith went out on her own, forming Judith Leiber handbags in 1963. She created some 3,500 handbags in such materials as leather, suede, needlepoint, fur and Lucite. But the bags that arguably made her name and her reputation were the jewel-encrusted minaudières that Leiber began making in the late 1960s when an order of gold-plated brass frames arrived damaged; in order to salvage them, she used rhinestones to cover the discoloration. The rest is handbag history, as the current Museum of Art and Design exhibition Judith Leiber: Crafting a New York Story (April 4, 2017 to August 6, 2017) can attest.

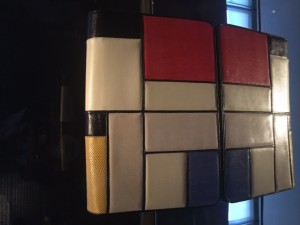

One of Leiber’s earlier purses on display at the exhibition.

Handbag lovers, design mavens and fashionistas will delight in wide array of bags on display, many from the early period. Even these show a distinct and unconventional flair, like the Mondrian-inspired lizard clutch or the bag formed from a large, gleaming nautilus shell. But it is with the minaudières that Leiber really breaks free. Divorced from utility, practicality and even function, these cunning, crystal-studded creations are to behold, not carry, to enshrine, not wear. Whimsical inspirations from the garden (watermelon, asparagus, tomatoes) or Asian art (the Buddha, the Chinese Imperial guard lions known as foo dogs) abound. So do pigs, birds, and a beehive. While not an exhaustive (or exhausting) show, it’s nevertheless a rich and satisfying one. And the wall notes and timeline provide excellent context in which to place Leiber’s achievements.

Handbags tell a story of women’s place in society as well as their slow march toward autonomy, so it seems hardly accidental that handbags began to assume their greatest importance in the 20th century, just as women began to enter the public domain. Handbags carry money, credit cards, keys, pens, passports, driver’s licenses—essentials for an independent life. Yet they also carry a seemingly endless array of other items—make up, hairbrush, comb, birth control, baby wipes, pacifiers, toys, hand sanitizer, gum, mints, lip balm, Band-Aids, ibuprofen, as well as Ziploc bags of Cheerios or Goldfish, all of which suggests the multiplicity of women’s roles: sexual beings, mothers, caretakers.

Judith Leiber’s glittering baubles will hold none of the above, and most have space for nary more than a single tube of lipstick. Many of them lack handles or straps, so that they must occupy the hands of their wearer at all times. Yet starting with Mamie, they have been coveted and carried by such women as Nancy Reagan, Barbara Bush, Greta Garbo, Mary Tyler Moore, Claudette Colbert, Beverly Sills and Hillary Clinton. Leiber, a Jewish woman who had been disenfranchised by war and politics, went on to create bags that are prized by women of influence and power. That perhaps is part of their lasting charm: these iconic creations look like fairy tale baubles for a princess in a ball gown, but instead they, like the women who wear them, have found their way into the great, wide world that lies beyond the castle walls.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.

Please wait...

Please wait...