The Lilith Blog 1 of 3

May 21, 2020 by Joan Roth

Original Pictures from the Real Events of “Mrs. America.”

Imagine America today, if only one women’s movement had arisen, instead of two…What the full power of womanhood might have wrought.

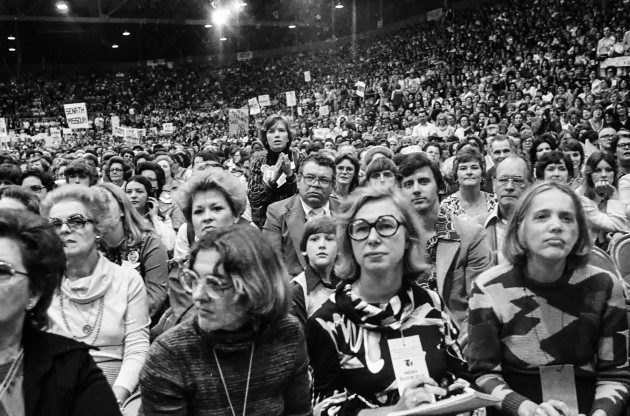

In July 1977, Harriet Lyons, then-editor at Ms. Magazine, and I attended the New York State women’s meeting in Albany, New York, in order to cast our vote for delegates to the first ever National Women’s Convention, funded by the federal government, that was to be held the following November at the University of Houston, in Texas. It was during this awesome moment that Bella was having one of her major fits, another friend recalls. Something triggered it–perhaps the selection of delegates.

Something didn’t go her way and she blew her top. Reminding us that the reason we women had come to Albany was to break down the barriers of equality by electing pro Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) delegates to the National Women’s Convention, where a plan of action would be forged to overwhelmingly guarantee passage of the (ERA). And, we didn’t play it right – when out of nowhere – a myriad of Pro-Plan, conservative women, appeared, like locusts, to get in their votes ahead of ours, electing themselves as delegates, to what organizers had anticipated would be a completely pro ERA slate.

Such were the dynamics of Houston. Even though the Senate granted a three-year extension for ratification of the ERA within a year of the Houston meeting; an unprecedented move and major post-conference achievement, despite the final failure of the amendment in 1982, at which point only 35 of the required 38 states had ratified the amendment.

In accordance with the Hulu series “Mrs. America,” now airing, the success of the conference had been blurred by the backlash from Phyllis Schlafly and her conservative minions, As wondrous as it was for us, the conference, it turned out, was also Schlafly’s big break, through which she turned the tide, freaking out feminists, by winning the loyalty of America’s housewives‚ according to Wikipedia, the Hulu series explores how one of the toughest battlegrounds in the culture wars of the 1970s helped give rise to the Moral Majority and shifted the American political landscape. Had feminists won their hearts instead, the country would be electing our third woman president by now, asserts Harriet Lyons.

Yes, Houston was a huge milestone, but it was also a crushing blow, particularly afterwards, when Reagan won in a landslide, woefully delaying the ratification of the ERA.

Thanks to Mrs. America this entertaining series brings back to life this cultural tango by interfacing a generation of women who brought lasting change to the world in spite of it all.

Think of the feminist movement in terms of where women’s lives were at during the late 1960s to mid 1970s, prior to the advent of second-wave feminism. Feminism spread across the western world, over two decades, to increase equality for women by gaining more than just enfranchisement.

Although turning Schlafly into a quasi-heroine, in part thanks to a sterling performance by Cate Blanchard, evoked the ire of some feminists who refuse to watch, more are drawn to its conviction that we’ve come a long way since then.

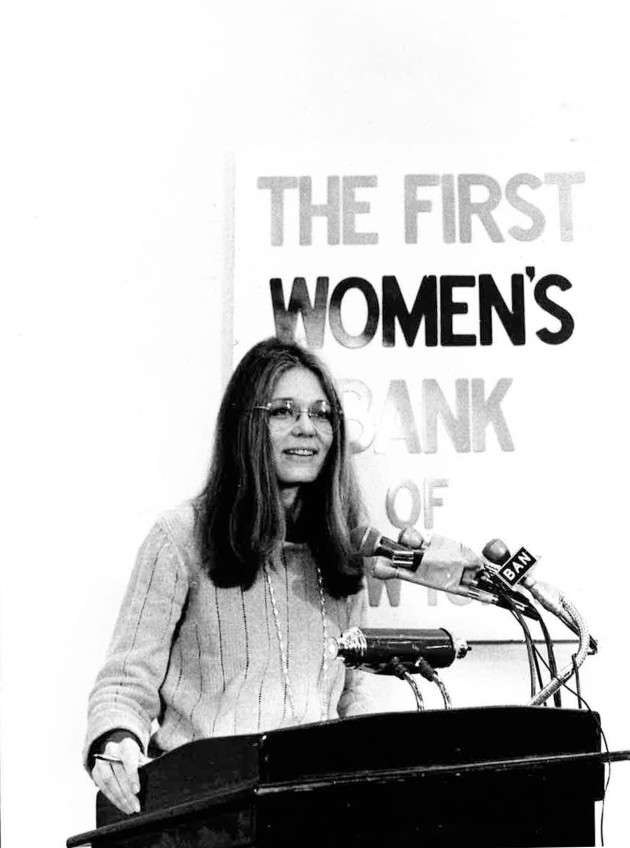

It’s fun to relive the story through the eyes of its designated heroines Betty Friedan, the mother of the movement and author of the Feminine Mystique, the book that forever changed our lives – even Gloria Steinem confesses to Betty, during one episode, that it changed hers; Bella Abzug, nicknamed “Battling Bella, U.S. Congresswoman (1971-73), and conference creator; Gloria Steinem, co-founder of Ms. magazine and nationally recognized spokeswoman for the American feminist movement as far back as the late 1960s.

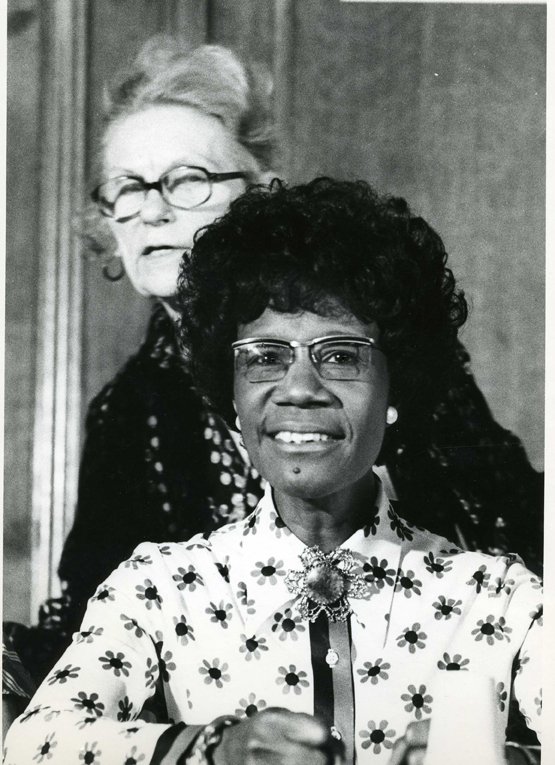

The series also features Shirley Chisholm, the first African-American woman in Congress (1968), and the first woman and African American to seek the nomination for president. And Jill Ruckelshaus, a pro-choice socially progressive Republican not pictured here. Left out are too many more vital women to mention.

Watching the series while in lockdown, while my children and grandchildren watch from afar too, is another kind of liberation, a homecoming of sorts. As a photographer in the early years of the movement, I was a follower, believer, viewing the world and its values through a feminist lens.

Besides the fact that she wasn’t on my radar, it was indicative of the times not to be conversant with Schlafly and her conservative movement. I already had more on my own overflowing plate of feminist ideals than I could handle as a single mother, attempting an expensive career without money. And, I hadn’t yet bumped into them.

But now, looking back, there is an added bonus to seeing the movement through my own eyes and through these photographs (and plenty more).

How privileged were we to openly spend our lives fighting for the principles we aspired to.

I chose to celebrate International Women’s Year (mandated by the United Nations) at the first National Women’s Conference to be held at the University of Houston to document the national plan for action forged by women yearning for equality.

In 1975, Congresswoman Abzug introduced a bill to hold a national woman’s conference in honor of the 200th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. On December 14, 1975, President Gerald Ford signed the bill into law and Congress approved a five million dollar budget to cover the costs for women to elect 2,000 delegates at 56 state meetings, to develop the plan whose political tenets would hopefully tilt the future of our country in favor of women. and which would be presented to both the Carter administration and to Congress.

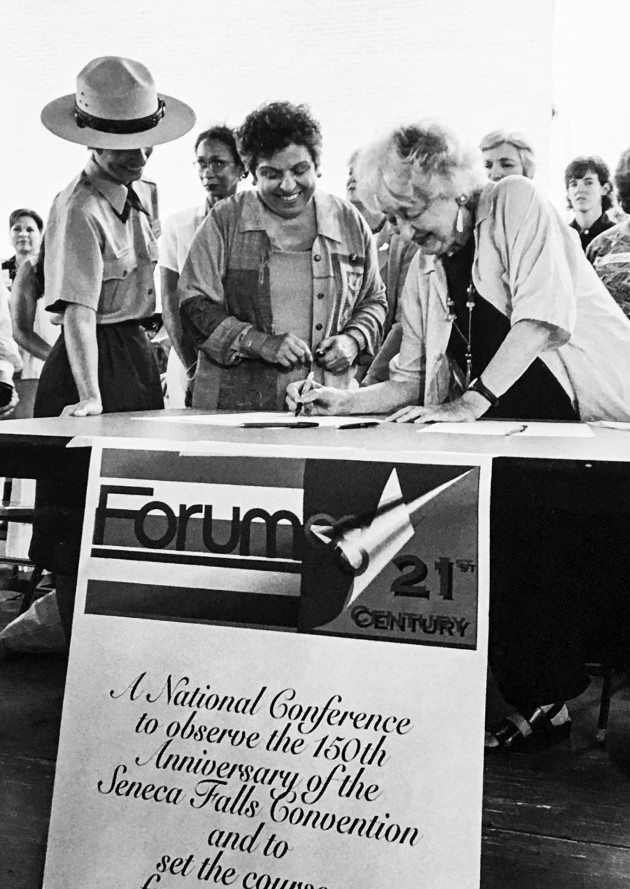

On September 29th, 1977, a torch was lighted at Seneca Falls, the New York, site of the first women’s rights convention held on July 19, 1848, which had launched the women’s suffrage movement. The torch was carried by a relay of runners the 2,600 miles to Houston, arriving the day before the conference began. Poet Maya Angelou wrote anew the Declaration of Sentiments, as a parallel to the manifesto passed by the 1848 convention stating women’s grievances and demands. And that would, more than seven decades later, secure women’s right to vote. The Declaration accompanied the torch on its race to the convention hall.

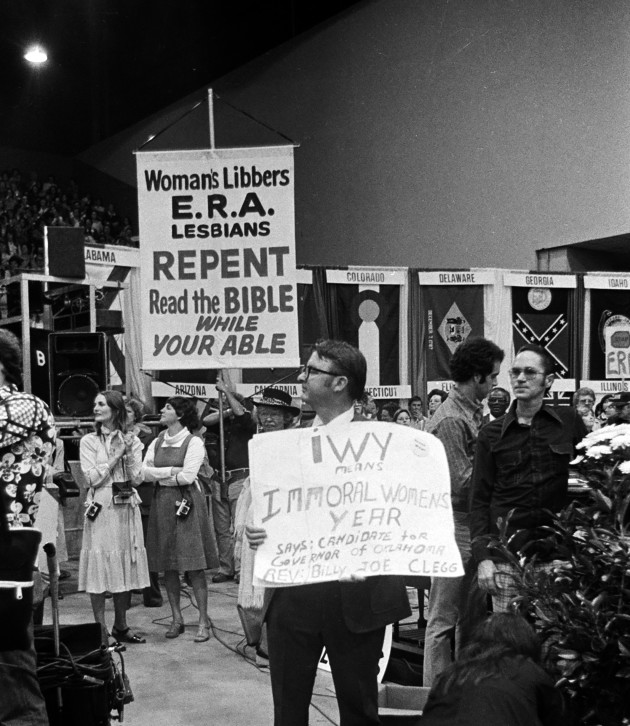

What I hadn’t anticipated then was to come face to face in my own rendezvous with the late Phyllis Schlafly and the massive resistance taking place at an oppositional rally across town, with 11,000 women, men and children crammed into Astro Hall, while 2,000 churchgoing wives, eager to voice concerns, that Time magazine attributes to their instinctive and philosophical objections to abortion and gay rights, which they were confident would erode family and obscure its male and female roles.

According to political consultant and independent scholar Charles McCaslin, who I was fortunate to meet at the conference, “Mrs. America” gets Phyliss Schlafly right, depicting her as a woman not easily fazed by challenge. She didn’t get angry and always remained pleasant–but, he adds, she was not really the gateway for the conservative movement, a long time in the making. She did, however, welcome to the Houston delegation, among traditional Republican activists, the wife of the former grand KKK wizard, as well as the founder of the Eagle Forum and more.

And so it was that I got to make sense of it all, to the best of my ability, through my photos.

From top to bottom: Shirley Chisholm, the first African American woman in Congress (1968) and the first woman and African American to seek the nomination for president

The way life used to be for women, NJ, 1975

“Revolutionary greetings!”

Gloria Steinem speaks at the opening of the First Women’s Bank

Betty Friedan signing the renewed Declaration of Sentiments at Seneca Falls, September, 1977

One of the last suffragists riding in a car at the Women’s Strike for Equality, the great women’s march down Fifth Avenue, August 26, 1970.

The Moral Majority’s Alternative Conference at Ashton Hall, Houston, 1977

Phyllis Schlafly, Republican National Convention, Detroit, Michigan 1980

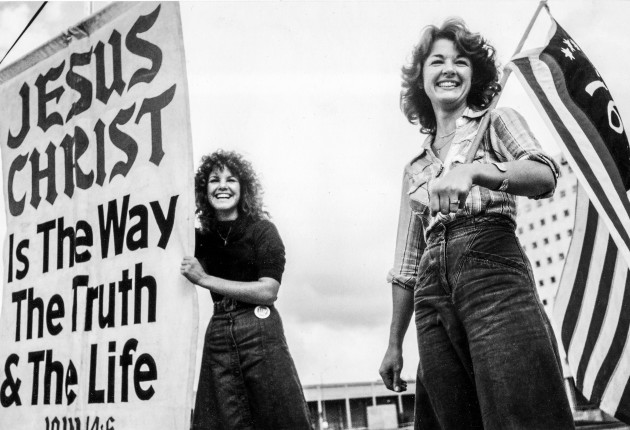

Reactionary Conservative women outside the Conference Center, 1977

With delegates former NOW president Karen DeCrow hails passage of the ERA resolution at the National Conference, 1977

Delegate-at-large Betty Friedan waits her turn to speak at the microphone amidst conservative activists attempting to take over the conference

“Passing the torch.”

The Moral Majority’s Alternative Conference at Ashton Hall, Houston, 1977

Please wait...

Please wait...