The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

June 11, 2019 Yona Zeldis McDonough

Conversation with a Curator: Avery Exhibit Features Works by Artist Wife and Daughter

“Summer with the Averys [Milton/Sally/March],” a remarkable show at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, presents the work of american painter Milton Avery alongside that of his wife Sally and their daughter March, who were both artists in their own right.

A Jewish girl born in 1902, Sally Avery (née Michel) studied painting at the Arts Students League and met Milton in 1924; she was 22 and he was 39. They married in 1926 and embarked upon an unusual artistic life together.

Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talks to Stephanie Guyet (who assisted Professor Kenneth E. Silver in mounting the show) about the special role Sally played in her husband’s life and career.

Sally Michel Swimming Lesson, 1987

YZM: Tell me about Sally’s background—where did she grow up and was her family observant?

SG: She grew up in Brooklyn. I do not know if the family was observant. She doesn’t mention whether they were or not in the interview transcripts that we read. In her Milton Avery catalogue essay, Barbara Haskell refers to Sally’s family as orthodox, but again, I can’t confirm that. I do not think that Milton and Sally practiced any organized religion.

YZM: How did her parents react to her marriage outside the faith?

SG: I think they were not happy with the marriage, but my impression is that they were more bothered by Milton’s lack of money/prospects. March did not mention that they were unhappy for religious reasons—and Sally’s mom was in March’s life when she was young (I think Sally’s dad had already passed away). This surprised me because I had read that they were unhappy with the marriage, so I asked March about it. She said, “They got over it.”

Man and Wife, c. 1950s

YZM: Can you describe her life as an artist?

SG: During the years that she and Milton were married, from 1926 until 1965 when he died, Sally’s fine art took a backseat to her work as a commercial illustrator. She was the primary breadwinner for many years. She wanted Milton to focus on his art, and so she worked. But every summer they traveled, and Sally took advantage of the time spent away from their life in the city to draw and make watercolors, same as Milton—to gather artistic inspiration. After he died, she was a wealthy woman who was able to travel extensively, which she did, and make art year round, which she did. Like Milton, in her art Sally focused primarily on the people and landscapes from her daily life. And she, too, employed abstracted forms but always maintained a representational style.

YZM: Some might say she suppressed her own desire for artistic recognition in service of her husband’s career, while others might see her choices in a more feminist light, as it seems she had a lot of decision making power in the marriage. What’s your opinion?

SG: I think it was a little bit of both. She definitely spent the bulk of their married life in support of his art and career, as opposed to her own. But March is adamant that Sally did not see herself as a martyr, did not feel at all resentful of her role. Sally was perhaps Milton’s greatest supporter, unwavering was her belief in his talent and artistic vision, and so my sense is that she saw her role, as supporter of that vision, as equally important. Barbara Haskell wrote that marrying Sally was the most decisive decision of Milton’s life; I agree. And she did, after all, have a successful career as a commercial illustrator, she drew a weekly column for the New York Times Magazine “Parent and Child” column from 1939 until 1959, so she was definitely ahead of her time.

Diver, 1976

YZM: Can you talk about her relationship with her daughter March, who is also an artist? Do you feel Sally was an important role model for her?

SG: March said, “A young girl sees her mother cooking, and so she cooks. I saw my mother painting, so I painted.” So yes, Sally had a strong influence on March, if nothing else than in setting the example of an artistic life, in the time and dedication spent on something that could be deemed extraneous or even frivolous. March was born in 1932, so again, this is quite impressive given the time, that she grew up seeing both parents, mom and dad, making art constantly, with a determination and commitment to an artistic practice.

YZM: What was the most surprising thing you learned about Sally when you were working on the show?

SG: Learning about Sally, and March, was the surprise. Learning about these incredibly smart and talented women who Milton was surrounded by, who influenced his work, and he theirs. Learning about the women around the canonical figure, and being given the opportunity to share their stories and their work with the public, was a wonderful surprise. When I asked March if she thought that Sally had sacrificed her own art for the sake of Milton’s, March said, “No, I don’t think it works that way. I think she did quite well.” And from everything that Ken [Silver] and I read, both she and Milton were very happy in their lives and marriage, so I suspect that March is right. I think Sally thought that she was in the presence of greatness and I think Milton did, too.

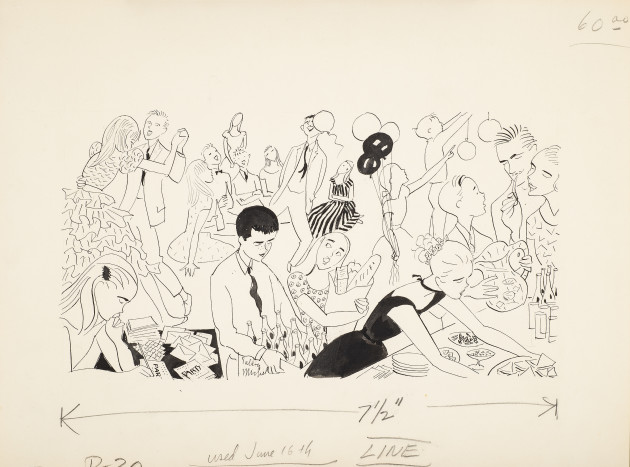

Care and Handling of Parties, June 16, 1957

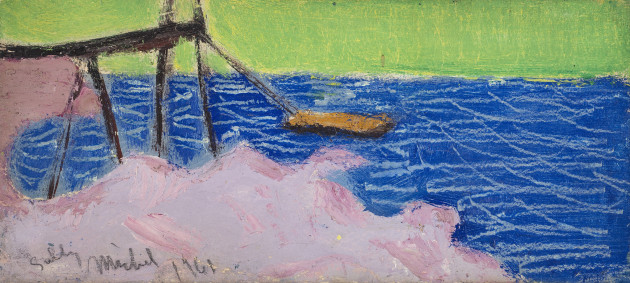

Untitled, 1961

Catch “Summer with the Averys [Milton/Sally/March]” at the Bruce Museum, Greenwich CT. Open through September 1, 2019.

Please wait...

Please wait...