The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

March 19, 2019 Yona Zeldis McDonough

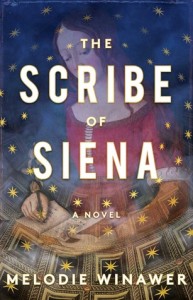

The Jewish Doctor Writing About Medieval Christian Spirituality

I met Melodie Winawer in a Brooklyn synagogue; so when I learned that she had written a novel steeped in Christian imagery and ritual, I just had to know why!

Equally interesting was Winawer’s background—she holds degrees in biological psychology, medicine and epidemiology. Below, Winawer talks to Lilith about her fascinating dual life as doctor/novelist, her attraction to history and so much more.

MW: I didn’t set out to write a story about 14th century Italian Christianity. Like any novelist, I did what my characters and my story led me to. The place, Siena, which I’d been to 10 years before I started writing the book, drew me in because of the way it exists in both past and present. Being there blurs the boundaries of time. Siena’s people live their centuries-old traditions with profound seriousness, and a deep emotional connection. And in Siena a mystery resides about what happened during the plague of 1348, an unsolved mystery that I uncovered as I began to learn more about Siena’s history. So my story took me there, and then.

Beatrice Trovato, the modern protagonist of The Scribe of Siena, is Italian-American. I didn’t exactly decide to make her that, that’s what she is, and I went with it. Once I followed her path to Siena, and her immersion in Siena’s past, I was of necessity surrounded by 14th century Italian Christian imagery. Any fiction writer probably has the same experience—we go where our stories take us.

YZM: What did you learn both spiritually and doing research?

MW: Where it took me taught me so much–not just historical facts, not just details about Italian medieval art, not just the rituals of the medieval church. My fictional immersion not only clarified the obvious differences between my life as a modern Jew and that of a modern or medieval Italian Catholic—but getting inside my characters and following them through their lives, I started to experience fundamental connections that transcend the boundaries of specific religious structures—in a visceral way, not an academic one.

Shortly after my book came out, a deeply religious Christian reader contacted me to tell me how my description of the divine, through the eyes of a 14th century Italian priest with stage fright, spoke directly to her experience, and that moved her deeply. I was moved too, by the way in which my immersion in an imaginary story and made up characters could bring me so close to someone whose experience is, theoretically, so different from mine. That is the beauty of fiction, it takes us—readers and writers both—into the lives and hearts of people different from us, fostering empathy and understanding.

YZM: What was it like making the leap into writing fiction after so many years in the medical profession?

MW: That’s a question I get asked so often—as if it were a leap. It wasn’t like that at all—not sudden, but steady, incremental, inevitable. I’ve always written since I could hold a pen. Before that I told stories, out loud to myself for hours in my room. (I was an only child until age nine, and spent a lot of time doing that.) I started to write a novel when I was fifteen.

The pressure slowly built until finally there was a perfect storm of circumstance in my life. We had sold our old house and our new one was under construction. We put everything in storage and moved in with my mom, with our three kids ages 2, 2 and 5. My spouse, who is a classical violinist, was practicing for a Stravinsky trio every night. I had no belongings. I was in limbo, and on top of that, I wasn’t reading anything and wanted to be lost in a story, one that would take me with it. So I decided, instead of reading one, I’d write it—I’d write the story I wanted to be in. And so I sat down and began to do that.

YZM: Did you tell your family?

MW: At first I didn’t tell anyone—I was afraid that with too much scrutiny it would disappear, and that it wasn’t real. Then slowly, as the story took shape, it gained momentum, and power. I told first my spouse, and then my mother. I remember that moment—about 100 pages in, when the world I’d started to build began to feel like it actually existed. I was having dinner with my mother and I started to tremble the way I did when I was a kid, when I was about to cry. I realized then that writing had taken on a major role in my life. Writing had begun to change my identity, and I knew it would start to alter the course of my career. I began to see how writing would take on as much power as my “day job’—my committed career in academic medicine and science. And it’s true: despite having published one novel and sold my second, and despite having so many stories in my head that are lined up waiting for their turn, I am still a neurologist and a neuroscientist. But I’m a novelist too.

YZM: Did your training and experience as a neurologist influence the way you approached this novel and if so, how?

MW: Because I am a neurologist, I am in the privileged but poignant position of helping patients who are losing the ability to move, see, think, speak, remember, and love. In medicine, empathy allows caregivers to understand the choices patients make about their lives, and to help them navigate the labyrinth of their illnesses. I may diagnose a patient with the same condition that killed my father, or care for a person whose symptoms mirror those I have feared in myself, or my children. So I need to keep enough distance to do my job well, and not lose myself in the process.

My experience of a physician’s empathy—its power for good, but also its dangers– led me to write The Scribe of Siena, and to create my protagonist Beatrice, a neurosurgeon. How far could empathy take her—could it extend to the written word, even words written hundreds of years ago? Could it blur the boundaries not only between self and other, but between times?

I’m not only a doctor, I’m a research scientist, and that experience influences how I write, too. The minute I started thinking and reading about Siena as a foundation for a story, I started running up against the question of why Siena fared so badly during the Plague. And I didn’t find one answer—I found conflicting answers. That became the historical question at the center of my story. In scientific research, my job is to explore the uncertain systematically, and be absolutely true to fact, or to experimental results. If I don’t do that, I will lose my job. But in fiction…uncertainty is a foundation for invention. That means I get to make things up. And that is intensely pleasurable—the absolute antidote to my satisfying, but highly structured, scientific work, in which I never get to make things up.

YZM: As an orphan, single woman and sole surviving sibling, Beatrice Trovato is both lost and found—can you elaborate?

MW: Trovato was not an accidental name choice—it means found in Italian, as you’ve cleverly noticed (no one has ever mentioned that before, believe it or not, at least not to me). This book is, at its heart, a story about belonging. It is the story of a woman who questions whether she is truly at home in the life she is living. This is a nearly universal experience: I began thinking about this seriously long before writing The Scribe of Siena. It’s like walking through the woods on a path, and much of the time the path is fairly clear, and you know where you are going. Then at certain points there are choices: you might see another path next to yours, and the trees clear enough so that you can not only see it, but step onto it, and head off in another direction. There are brief instances in life when it is possible to cross over, from one path to another, to a new way of being. And if you do…you might lose your way, but find another. Beatrice loses so much, but the losses unmoor her, giving her freedom to reconsider and change the trajectory of her life. The Scribe of Siena is the story of how we are both lost and found.

YZM: Let’s talk about time travel—why did you make the choice to include it and what does it enable you to accomplish?

MW: Fundamentally I guess I believe that time is not linear, and that the best way to understand the past is to realize how it intersects with the present, how the boundary between times is not so distinct as the strict orderly timeline of history makes it out to be. Every past is alive, right next to us, full of people who are not as different from us as we think. Juxtaposing the past and present, allowing them to overlap, allowing one period in time to be seen from the perspective of another, all of these strategies make it possible for us to learn from the past, and foster empathy for people who seem so different from ourselves—not just in other times, but in our own. But honestly, for me as a writer, it’s also just more fun.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.

Please wait...

Please wait...