The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

March 22, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

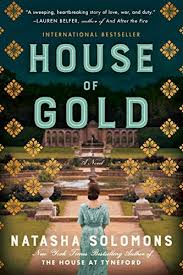

A Breathtaking Novel Set on the Eve of World War I

Set in the years before and just leading into World War I, House of Gold is a vast, enthralling tapestry of a novel. The story moves seamlessly from character to character and place to place, all the while picking up speed and momentum as the war looms ever closer.

Set in the years before and just leading into World War I, House of Gold is a vast, enthralling tapestry of a novel. The story moves seamlessly from character to character and place to place, all the while picking up speed and momentum as the war looms ever closer.

Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough chats with author Natasha Solomons to ask her about what drew her to the subject and what she learned along the way.

YZM: What inspired you to write a saga about a Jewish banking family?

NS: So much Jewish history of the last century is about oppression and death. Yet, the Rothschilds were a symbol of power and of hope to other Jews, particularly those poor and subjugated in Eastern Europe.

The fictional Goldbaums are similarly powerful and almost unimaginably wealthy, but unlike most of the aristocrats in Europe at the time their wealth is earned. They are more like the American industrialists or new money, and were considered by many as gauche and bourgeois, viewed with even more intense suspicion by the establishment because of their Jewishness. To me, that makes the Goldbaums interesting— to be both singularly powerful, intricately involved in international affairs and needed by governments and emperors, and yet still be vulnerable and isolated.

YZM: How much here is based on the fabled Rothschilds and how much did you invent?

NS: I think every historical novelist starts with a huge amount of research, but the truth spins into fiction. Sometimes things that are true don’t feel true on the page! For instance, when writing about the Goldbaum gardens I actually had to reduce the numbers of glasshouses and gardeners—the Rothschilds had so many that I worried a reader wouldn’t believe the fiction.

There were several incredibly wealthy Jewish banking families in the early twentieth-century. The Rothschilds were probably the most famous but there were also the the Sassoons (the ‘Rothschilds of the East’), a Sephardic lineage almost as wealthy and as powerful. Ernest Cassell was one of the wealthiest men of his day as well as a friend of British prime ministers Asquith and Churchill. There were the Goldsmiths, the Montefiores and the Montagues.

Yet the novel’s characters are all imaginary. Some are inspired by my own family stories. My great-great uncle Karl was a friend of Einstein and developed a theory on black holes, known as the Schwarzschild Continuum. There is even a crater on the moon named after him and Einstein wrote his eulogy. It was Karl who inspired the character of Otto in House of Gold.

YZM: You’ve said that you had a relative who was tangentially connected to the Rothschilds; can you tell us more?

NS: Hanging in my parents’ house is a portrait of one my ancestors in the Frankfurt ghetto: a serious man in a black skull cap. He was a tutor and neighbor to the Rothschild children. In the ghetto families had to choose a sign to distinguish themselves—my ancestors, the Schwarzschilds, picked a black shield, and the Rothschilds a red one.

This tiny brush with the famous Rothschilds amused and intrigued me. Yet following the journey of both families—one wildly successful, one modest (with the odd painter, scientist and gambler) —is what helped me discover the story for my novel House of Gold. I wanted to write about a family of huge wealth and power, but set apart and considered “other” because of their Jewishness.

YZM: Let’s talk about your character Greta Goldbaum—a Jewish feminist before her time?

NS: I’d like to think that there is a some of me in Greta, and also some of my daughter, who although small is utterly willful. The rest of Greta is fictional although she is inspired by characters like Elizabeth in Elizabeth and her German Garden by Elizabeth Von Arnham. I think the word “feminist” is tricky for the period:mGreta herself wouldn’t recognize it. She is not a suffragette and is irritated by Edith’s tactics to gain the vote. But, Greta is outraged at the way men are prioritized over women, and she quietly refuses to obey almost any instruction given to her by her husband or father-in-law. She is also unembarrassed by the fact that she enjoys sex – not something that many women admitted then, even to themselves. This is a quiet and personal act of rebellion, but no less profound.

YZM: What about the role that gardening and the study of insects play in the novel—are these particular passions of yours?

NS: I am not yet a passionate gardener (weeding takes as much time as editing, and having two small children I can either weed or edit) but I adore my garden. My studio looks down on the garden and out beyond to the hill. The English are celebrated for our love of gardens, and English writers have always understood that characters reveal themselves through their gardens. The outside spaces in this novel are really explorations of the characters: the Goldbaums are passionate about gardens as a result of having been banned as Jews from the public parks in Frankfurt. There were no gardens in the ghetto. Now, possessing incredible wealth, they choose to create remarkable and splendid gardens both to display their power and to remind themselves of how far they have come.

The Goldbaums are famous for their formal parterre gardens (immaculate low hedges, gravel walkways, pristine beds of annual flowers, fountains and statuary). But, I wanted to show Greta as a different kind of Goldbaum, who hankers for a different kind of garden. She worries that although her mother-in-law encourages her to create a garden, it’s a ruse to re-make Greta herself into the right kind of Goldbaum woman: as ordered and self-contained as a Goldbaum parterre. She wants to rebel. She wants a garden in which to misbehave: one of rambling roses and hidden corners and wildflowers and long grass. A garden of defiance.

YZM: The novel brims with period detail and description; can you describe your research process?

NS: I researched this novel differently from my others. Usually I write and research all at the same time. However, in the early stages of House of Gold I was actually reading an email on my phone (coincidentally from my US editor) and absolutely not concentrating on closing the car-door properly and managed to trap my finger and break it. So, instead of writing, I found myself having surgery on my finger and reading a vast amount for several months, quite unable to type. I’ve read financial histories, social histories, medical history, diaries translated from German, Russian; women’s journals and British newspapers; books on the pogroms and on German and Austrian blood libel trials. I’ve interviewed garden historians and visited historic gardens and attended lectures…

YZM: What’s the one thing you wished I’d asked that I didn’t?

NS: My favorite flowers are Sweet Peas. The scent of an English summer. The fact that they only last for a day or two makes them even more precious.

Please wait...

Please wait...