The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

January 30, 2019 by Eleanor J. Bader

From Yesterday’s Institutions for the “Feeble-Minded” to Today’s Prisons

Anne E. Parsons was a teenager when her mother told her that her grandmother had had a sister named Ruth who’d spent 40 years at the Delaware Colony for the Feeble-Minded at Stockley, an enormous residential hospital in Georgetown, Delaware.

“Aunt Ruth was not a secret, but, at the same time, the family did not speak openly about her,” Parsons told Eleanor J. Bader in a recent telephone interview. “It wasn’t until I was an adult that I understood the weight of what it must have been like for both Ruth and for my family.”

Great aunt Ruth’s story has driven much of Parson’s research. Her latest book, From Asylum to Prison: Deinstitutionalization and the Rise of Mass Incarceration after 1945, explores the ways psychiatric hospitals and prisons have intertwined to exert social control on US residents.

In their hour-plus conversation, Parsons—an assistant professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro— and Bader discussed this transition and touched on the need for holistic solutions to crime, punishment, and mental illness; the American penchant for retribution; and the growing movement to close US prisons.

Eleanor J. Bader: Let’s start with your great aunt Ruth. What do you know about her?

Anne E. Parsons: My great aunt, Ruth Scher, was born around 1913 and was placed in the Stockley Center in 1929. She lived there until she died in 1969. I know that she had severe physical and developmental disabilities and was the fifth of six daughters born to my Ukrainian Jewish immigrant great grandparents. Ruth was born in the US—had she been born in Ukraine the immigration authorities at Ellis Island would not have allowed her to enter the country—and in 1929, right before the Great Depression, her working-class family became unable to care for her. At the time, there were few options for people with severe disabilities so my great grandparents placed her in Stockley and visited her regularly for the rest of their lives. Her siblings also visited, but the family did not let other people go to see her.

In the early 20th century, there was huge stigma around so-called feeble-mindedness and intellectual disabilities. These types of conditions were thought to be hereditary so they were rarely talked about. And even though my great grandmother, Ethel Scher, was a member of a Jewish society that cared for the sick, I don’t know of any resources that they, themselves, received to help with Ruth’s care.

EJB: In addition to the developmental disabilities, what other conditions landed women in psychiatric facilities during this era?

EAP: Mental health institutions always included people who were labeled as sexually deviant. This included homosexual men, lesbians, and others who transgressed gender norms.

EJB: Before psychiatric hospitals began closing in the 1970s, men and women were confined in pretty equal numbers. Why were so many women held in these institutions for what was essentially long-term incarceration?

AEP: One of the main intentions of mental health institutions in the early 20th century was to prevent reproduction. At one facility, the Laurelton State Village for the Feeble-Minded in Laurelton, Pennsylvania, female patients were released as soon as they became menopausal. Other places had high rates of sterilization because the goal of institutional commitment was control of sexuality and fertility.

EJB: Did the media have a role in pushing these so-called treatments out of favor?

AEP: There is still a fear-based politic around mental health conditions that is driven by today’s media. At the same time, the media can shape—and have shaped– people’s perceptions for both good and bad. Media perpetuates stereotypes, but media can also present a critique of the ways we, as a society, lock people up and throw away the key.

This is where books like Mary Jane Ward’s 1946 novel, The Snake Pit, jump out for me. Ward’s story became a major bestseller and then an award-winning film. It pushed the needle to improve how people with serious mental health conditions were treated. Ward humanized the issue by drawing on her own experience as a patient in Rockland State Hospital in New York state to highlight the ways psychiatric hospitals mistreated patients. She wrote powerfully, documenting the zoo smell, the locked doors, and the complete loss of freedom. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Ken Kesey’s 1962 novel, had a similar impact.

More recently, news stories about the 2015 suicide of Kalief Browder, a 22-year-old African American man who had spent two years in solitary confinement on Riker’s Island, have helped activists push for the closing of that prison.

EJB: Can you explain how the closing of psychiatric hospitals in the 1970s led to today’s unprecedented level of incarceration?

AEP: First, let’s step back. Of course, when mental hospitals closed, it was an advance for the rights of people with psychiatric conditions. Nonetheless, the closures never addressed the real, underlying issues that people were facing, the actual poverty and racial and gender discrimination that they experienced. If we don’t pay attention to these things, we run the risk of developing new forms of institutionalization. Right now, we’re seeing the closing of some prisons; simultaneously, we’re seeing an increasing number of immigrants being held in detention centers.

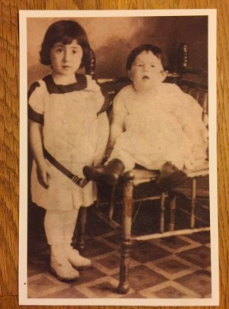

A photograph of the author’s Aunt Ruth Scher as a baby (sitting on the chair), next to her Aunt Signa Scher.

If the current decarceration movement is going to succeed, it will have to deal with the issues that most people coming out of jail face, from lack of education, to lack of healthcare, job opportunities, affordable housing, and available social services. The closure of mental hospitals in the 1970s and 80s came at the same time as cuts to social service organizations, so it should not surprise anyone that large numbers of people with mental health conditions found themselves living on the streets.

Basically, it comes down to this: Sexism, racism, and economic inequality intertwine with mental health and criminal behavior and we have to address these issues if we want a society where human well-being is prioritized.

EJB: Why do you think the U.S. has often been so punitive?

AEP: There is a 2010 book called Texas Tough by Robert Perkinson that argues that today’s mass imprisonment is rooted in southern slavery. But slavery was also present in the north. Still, Parkinson was right: Our nation’s deep roots in slavery have perpetuated complex systems of violence. I see this as a core reason for our reliance on the surveillance of criminality and desire for punishment or retribution.

I think another main cultural factor is the rugged individualism that our country was built on. The idea of putting everything on the individual means that if someone is socially different—or does something that is generally not approved—it can justify removing them from society.

EJB: Are there any programs that you see as models for how people with mental illnesses should be treated, especially if they are in prison?

AEP: The reality is that today’s prisons and jails are filled with people with serious mental health conditions. The most recent statistics say that about 30 percent of women and 15 percent of men who are incarcerated have a severe mental illness. In addition, 68 percent of people who are incarcerated have issues with substance abuse. This is particularly impactful for women who have histories of trauma, since needless to say, being in prison exacerbates the trauma.

As for models, what I think works best is a multi-pronged approach. Groups like Mental Health America do advocacy and try to divert people away from prison by advocating for crisis intervention teams that utilize alternative sentencing courts and structured social service programs. They also train people to advocate for getting people who are leaving jail or prison adequate mental health care.

Another program I consider a model is called Benevolence Farm in Graham, North Carolina. It’s a place for women who are leaving prison to live once they get out and connects them with medical and mental health care as well as employment and educational opportunities. The women can stay on the Farm for up to two years. It’s a tiny program but it offers a different vision of what is possible. Rather than pulling people out of society, it serves them at the point at which they need help.

My synagogue in Greensboro, is working to support and fundraise for Benevolence. I’m proud of this. Actually, the Reform movement has made criminal justice reform one of its central social action priorities.

Another model program, in Laurinburg, North Carolina, is called Growing Change and it is taking a closed prison and turning it into a place where juveniles can learn to farm or become entrepreneurs. A former solitary cell block will be turned into a recording studio.

EJB: Asylums and mass incarceration are potentially depressing topics. Have you been able to sustain a sense of optimism?

AEP: Well, when I think of my Aunt Ruth, I think about the options she would have if she had been born 60 years later. We still have a long way to go, but today there are many more supports for people with intellectual and physical disabilities than there were 100 years ago. This shows that we can make positive change. My hope is that 100 years from now we will have moved people out of large carceral institutions and will fully support everyone’s human development.

Please wait...

Please wait...