The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

October 11, 2018 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

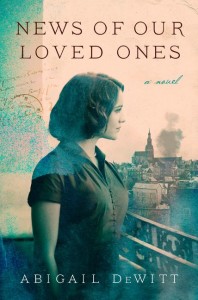

Nazi-Occupied Normandy and a Family’s Wartime Secrets

Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talks to Abigail Dewitt about her lyrical and haunting novel, which tells the multi-generational story of a French family and the way the Nazi occupation—and the Allied invasion—have shaped their lives.

Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talks to Abigail Dewitt about her lyrical and haunting novel, which tells the multi-generational story of a French family and the way the Nazi occupation—and the Allied invasion—have shaped their lives.

YZM: You write so beautifully and intimately about France—what is your connection to the country?

AD: Thank you! I’m a dual citizen of France and the U.S. My mother was a young, French, theoretical physicist when she came to the States in the late 1940s to study at the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study. She’d lost half her family in the D-day bombings and intended to go home after two years to re-join her three surviving siblings, but instead, she met my father and married him. Still, she was deeply committed to helping r-build France after the war, so, to make up for marrying an American, she founded the École de Physique des Houches in the French Alps. She and my father taught at the University of North Carolina, but we spent every summer in France so she could run the institute and we could know our relatives.

My mother’s family was very close-knit, and, though they admired my father, it broke their hearts that my mother had moved to the States, that my sisters and I seemed more American than French. Most of them did not speak English, and our French was never quite as good as our English. I loved France, but also felt a step behind there, and I was haunted by my family’s war experiences. For a long time, because I often failed to “get” things in French, and because my family’s grief about the war was both pervasive and unacknowledged, I thought of France as a place of mystery and sorrow. Much of my writing has been inspired by this sense of belonging and not belonging to a family and a culture marked by tragedy.

YZM: Why did you avoid a chronological telling of the story?

AD: The novel began for me with the story of the daughter awaiting the bombs—I wrote that chapter years before the rest of the novel—and then I found myself drawn into the other characters’ stories, into the story of a whole family shattered by the events of June 6, 1944. In some instances, I needed to go back a decade or more before D-day to show the full impact of the bombing on a particular character.

Ultimately, the family—loosely based on my mother’s family—became as much a character in this novel as any individual.

I’ve also always been fascinated by the different ways two people will describe the same event. If I asked one relative what our family went through during the war, she might talk about clever food substitutions; another would talk about a Jewish neighbor who disappeared. Only my mother ever talked about the family home being reduced to rubble. It seems to me that the truth is rarely contained in a single version of a story, but, rather, in the echoes and discrepancies between one telling and another. I wanted to respect the variety of perspectives these characters represent, and because each character has a different defining moment, it meant jumping around in time.

YZM: The Jewish characters here are mostly seen and described from points of view not their own and yet their stories form a consistent thread. How did that choice come about?

AD: The Jewish family members I knew or heard about were men—the Jewish doctor my grandmother had an affair with, and his younger brother, my beloved great-uncle—but I wanted this to be a novel of women’s voices. In “The Jew & the German,” I let a girl imagine what had happened between the two men, rather than let the men speak for themselves.

My Jewish heritage was also a relatively late discovery. My mother was in her fifties when she learned that her biological father was the family doctor, who was both Jewish and a member of the Resistance. During my most formative years, I didn’t identify as Jewish. I grew up haunted by the question that has haunted so many French people of my generation—would I have been a collaborator or a resister?—but for a long time, I was spared the horror of knowing that my grandfather died at Auschwitz. If I’d drunk that knowledge in with my mother’s milk the way I drank in the knowledge of D-day, and if I’d been able to spend more time with my great-uncle—the only one of his siblings who survived the Holocaust—I’d have a very different story to tell. I adored my great-uncle and felt a strong connection with him, but he died a few years after I met him, and most of my experience of family and of war survivors has been female. Still, both my grandfather and my great-uncle had a major—if, for a long time, unacknowledged—impact on the family, and I wanted to include their stories.

YZM: The novel raises questions of identity—who is French, who is American. Do you feel those issues have particular relevance today?

AD: As nationalism spreads across Europe and the U.S., I’ve been thinking a lot about the difference between a sense of identity which unites people and one which seeks to keep people out. Sometimes, it seems, there’s a fine line between the two. I’m proud of being half French, of being mostly bilingual, of making a mean crêpe, but at the same time, one of the benefits of growing up in two countries is that it forces you to see the arbitrariness of cultural norms. One tiny example, from the dinner table: My American father insisted that, when you were not slicing your food, your left hand belonged on your lap; my French step-grandfather insisted that your left hand always be visible. Both men were repelled by nationalism, but both insisted—often passionately—on the norms he’d been raised with.

Worrying about table manners is a trivial, almost comic thing compared to the horror of nationalism, but both, perhaps, indicate a failure of imagination. A distorted sense of what defines good behavior. To write thoughtfully about the clash of cultures—whether as comedy or tragedy—requires us to explore the ways in which our connections with one another transcend national identity and culture. I hope I’ve done that in this novel.

YZM: And you write about what the arbitrariness of borders can do to families, which feels extremely of the moment.

I that I’ve managed to illuminate a central irony of nationalism: In the 1930s and 40s, and again now, nationalism, for all its insistence on keeping like with like, inevitably tears families apart. Homes are bombed, children are separated from their parents. In my novel, only Polly, born years after the war, can “afford” to worry about national identity—the others are too consumed by a struggle to survive—but Polly is still scarred by the previous generation’s suffering. If Polly were speaking to this question, she’d say that all nations should be abolished, all borders dissolved. My own vote would be for everyone to have the benefit of growing up in many cultures. Two is good, but I wish I knew other, more varied cultures as well as I know French and American culture.

Please wait...

Please wait...