The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

March 5, 2018 by Mindy Isser

Why Sending Pizza to West Virginia’s Striking Teachers Is a Mitzvah

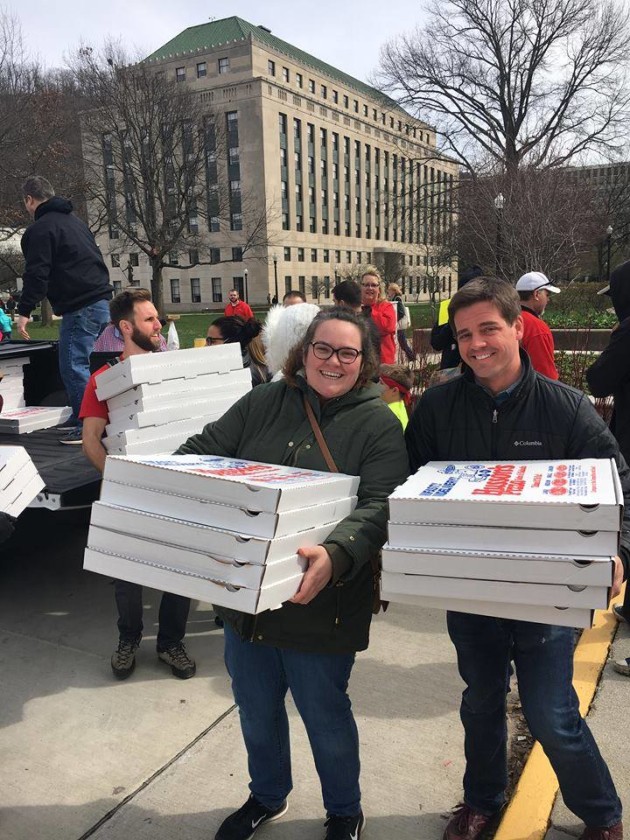

Teachers in San Francisco sent pizza to the picket lines to support the strike. Here, the moment when the food arrives. Photo credit: Eric Blanc.

Like most leftists and other concerned humans, I’ve been following the West Virginia teachers strike as closely as I can. Today marks the eighth day of their illegal strike—in West Virginia, public employees lack both the right to strike and to bargain collectively. But teachers and other public school workers went on strike anyway, because their pay ranks 48th in the country, and their health insurance premiums continue to increase. They’re promising to remain on strike until a law is passed guaranteeing them a 5% raise.

Like thousands of others, I donated to the strike fund, but it didn’t feel like this was enough—so I ordered pizza.

As a Jew, I emote with food. Bad breakup? Made it out of surgery? Had a baby? I’m on my way over with food. Whatever it is, there’s something about feeding someone that communicates everything you need to say—and, sometimes, the things you can’t say.

In my family—and I imagine, in many Jewish families just like mine—everything we do revolves around food, and most of my family memories are food-related. When I think of my bubby, I think of her in my childhood kitchen, chopping carrots with bandaged fingers; or in her apartment in Atlantic City, roasting chicken til the skin got crispy; in the morning, eating oranges, sliced into perfect, golden triangles; at lunch, tuna fish sandwiches with Jersey tomatoes.

When she saw me and my siblings, the first thing she’d ask is if we were hungry. And we were, always. And when we were done, she’d say, did you have enough to eat? My bubby wasn’t fancy, but everything she cooked tasted better than anything else. When we left, she hugged us tight and let us stuff our pockets with the candy reserved for her card games.

But feeding people is not just a kindness, it’s a mitzvah. For Jews, food is a celebration, yes, but it’s also obligatory. We’re commanded to feed ourselves and those around us—especially after the fulfillment of a ritual or an important life event. Sharing a meal celebrates our connectedness both to ourselves and to God.

So when I saw photos of the strike lines on Twitter—families with their children, students supporting their teachers—I knew that they needed to be fed. Plus, as has been pointed out, providing food on the picket lines allows workers to stay and protest longer. I put the call out on social media, and both friends and strangers chipped in. People gave $5, $10, $20—all to get pizza to the workers on strike, to feed people they’ve never met. Maybe we couldn’t break bread together, but we could at least get pizza delivered. Together, we raised more than $600 in just over an hour. Everyone understands the power of food, and even the hardest fighters have to eat.

During the Passover seder—when we’re starving from asking question after question—my dad always says, “Okay! They tried to kill us, we won, let’s eat!” The story of Pesach is one of liberation, yes, but it’s also about food. What we can eat, what we can’t; what it all means. Sweeping up every crumb of chametz, dipping karpas into salt water to symbolize our tears during slavery, eating maror to taste the bitterness of our labor. And every year, many of us add new foods to our plates—an orange, to show that women belong everywhere, including the bimah; an olive, to symbolize our solidarity with Palestinians, and our hope for a peaceful future. Food has meaning. It’s a powerful reminder of who we are, where we come from. It’s the knot that binds us to each other.

Eating is how we celebrate after a victory, after they don’t kill us. No matter what happens in West Virginia, the teachers there have won. They’ve reignited the labor movement, inspired millions, and shown that they’re willing to risk everything for their students and their profession.

How can you thank people for that? What can you say that doesn’t sound hollow and insufficient? But food says it all. Feeding someone says, I want to make sure that you’re okay. And in this case it says, thank you for taking care of all of us—now let us take care of you.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.

Please wait...

Please wait...