The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

October 2, 2017 by Danica Davidson

An Interview with Eva Schloss, Anne Frank’s Stepsister

Eva Schloss

Eva Schloss is an Auschwitz-Birkenau survivor, author, Holocaust education activist — and stepsister to Anne Frank. She travels the world to tell her story, and on September 7 she was at a Western Michigan University event presented by the Chabad of Kalamazoo. She was interviewed by her close friend and now co-presenter, Dr. Tami Weiss, Professor of Art Education at the University of Wisconsin-Stout. Weiss met Schloss in 2015 when she produced a play about Eva’s life, And Then They Came For Me: Remembering the World of Anne Frank by American playwright, James Still.

Schloss told about how she escaped Vienna after the Auschluss with her parents, Erich and Elfriede (Fritzi) Geiringer, and her older brother Heinz. They eventually settled in Amsterdam, where she became friends with her neighbor, Anne Frank, who was the same age. In 1942 the family went into hiding, and in 1944 they were betrayed by a Dutch nurse who had pretended to be helping but who was really a double-agent for the Gestapo. It was Schloss’s 15th birthday.

On the train to Auschwitz, Heinz told Schloss about paintings he’d made in hiding and had concealed below floorboards. Erich and Heinz perished days before liberation, and when Schloss later went in search of her male relatives in the men’s part of the camp, she came across Anne’s father Otto Frank instead. The three survivors—Schloss, Fritzi and Otto Frank — eventually drew close, and Fritzi and Otto married, thus making Schloss Anne’s stepsister.

After liberation, Frank came into possession of his daughter’s diary, crying repeatedly as he read it over the course of three weeks. Schloss, meanwhile, found her brother’s hidden paintings right where he’d said they’d be—under the floorboards of the place where he was in hiding. Schloss’s books, Eva’s Story and The Promise tell this story, and more. I asked Schloss about her experiences.

Danica Davidson: How did Otto Frank decide to publish the diary?

Eva Schloss: He wasn’t sure. He was in two minds, obviously, because diaries are private, but he was convinced by a history professor, Professor Romein, who said that it was his duty to share it with the world. And then he edited it, because Anne had a bad relationship with her mother and the dentist [who was in hiding with them], and he thought it was too painful to publish all this. He didn’t add anything, just took away things. They say next to the Bible, [Diary of a Young Girl] is the most read book. It’s already gone over generations.

DD: What did you think of this early censorship of the diary?

ES: I can understand that he didn’t want his wife to be put in such a situation that communicated publicly that her daughter hated her. [Anne] said, “I hate her.” Very often teenage girls have a bad relationship with their mother. Hopefully it would have changed if they had both survived. I think it was perfectly all right that he took it out. But after he died, Otto left the diary to the Dutch government, and they decided they would publish everything. So if you buy now a copy, it’s not edited. It is as Anne wrote it.

DD: What do you hope to accomplish with your books?

ES: To teach. Eva’s Story is very graphic. I describe everything really how it was and [how] I felt. Not so much comments about it, but just facts. And then my second book, The Promise, is a book really about my brother. Anne said in her diary when she died she would become immortal, which she has become, and I think we all would like to be immortal. My brother was very much afraid of dying. Nobody knows about his life, what he has achieved in his short life. So I realized I’d write a book about him, so that he is remembered. Yad Vashem in Israel tries to find all the six million names of the people, because in the Polish or Russian villages, there were often whole families who disappeared and nobody knew their names. There is time to find still people who know that those people have lived, so at least they can put their names down.

DD: And how are you honoring the memory of your brother and your father?

ES: To talk about them, what wonderful people they were. And as I say, my book, The Promise, is mostly about my brother who did not survive the concentration camps; it is about who Heinz was—a great musician and painter. Tami [Weiss] and I are working on a book about him. He also wrote many poems, and there’s an exhibition made in South Africa about his life as well. We’re trying to get it out to America soon.

DD: Where can people see Heinz’s artwork?

ES: Heinz’s paintings are in the Resistance Museum in Amsterdam. The originals stay there. Copies of the painting are touring, and the next tour will be in La Crosse, Wisconsin in a couple of weeks.

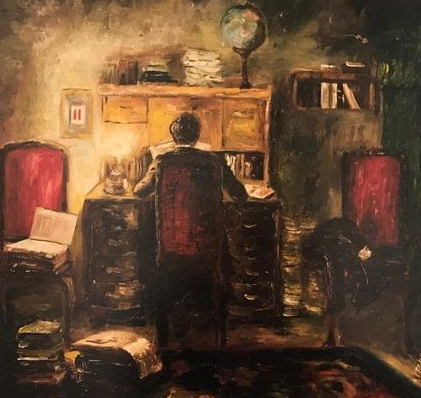

One of Heinz’s paintings. Copies are currently on tour, though the originals are at the Resistance Museum in Amsterdam.

DD: How can art and storytelling better teach people about the Holocaust?

ES: This is how people kept their sanity during the Holocaust and throughout history—to express themselves. You saw as well, in the First World War, wonderful poetry came out from people who were in the trenches. In terrible situations, people express themselves in painting, in poetry, in music, and in all kind of arts. The painter Van Gogh was put in an institution. He painted there, and he said something like, “This is why I can still be alive, because I can express my soul.” Everyone can draw; they don’t have to be “good” artists. It’s certainly a way to get your feelings out, which is important.

In England a huge tower block [apartment building] was burned, and 80 people perished. Have you heard about that? It was not fireproof, and the whole thing went up in fire. Many children died but many were saved. They are in special schools now; and what they’re doing is drawing about this terrible accident in order to cope. They get their emotions out in drawings.

As Tami says about viewing art from the Holocaust like my brother’s paintings, “By looking at art, we can sort of know the people who made it; and, in a sense, we can keep them alive.”

DD: Do you think people who aren’t survivors can express the Holocaust in art well, or do you have to have been there?

ES: It’s better of course if you were there and can express it. But we won’t be here forever and so we hope there will be other people who carry on, like Tami. I’m sort of training her now to take over when I’m not here anymore. She’s heard my story many, many times; and through our friendship, she knows me in depth. It’s not quite the same as having a firsthand account, but it’s still important and effective.

DD: What sort of educational work do you do?

ES: I educate people about what has happened in the Holocaust so that they know. I just got a letter from a German girl, 14 years old. She came across a film I was in and she looked me up on the internet. She got my book and wrote me a long, long letter: “I didn’t know anything about it, and I’m starting to get interested now that I know all this. And how could my people, the German people, do this?” She wants to stay in touch with me. Every day I get invitations to speak from people who heard me speak or read my books. So I do spread the word. At the moment, things look quite dark, but my outlook is that there are bad periods and good periods. You must never give up hope. We can fight the bad periods, and we can overcome. And there is always something good afterward. So basically I am an optimist.

DD: What have you learned about humanity from your experiences?

ES: When I came back out of the camp I became an atheist and didn’t believe in God. Because, if our God is powerful and a “good” God, how could He tolerate that? So, I also didn’t believe in humanity. I was rudderless and I was very, very, very miserable. But Otto Frank had lost everybody—his entire family; and he was not bitter. I learned a lot from him. He would say, “Hate won’t take you anywhere. Love lifts you up.” I eventually experienced that this was true and that’s what I’m trying to do—to see the good in people. You will find kind and amazing people.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.

Please wait...

Please wait...