The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

March 30, 2017 by Ilana Kurshan

You May Want to Feed My Children

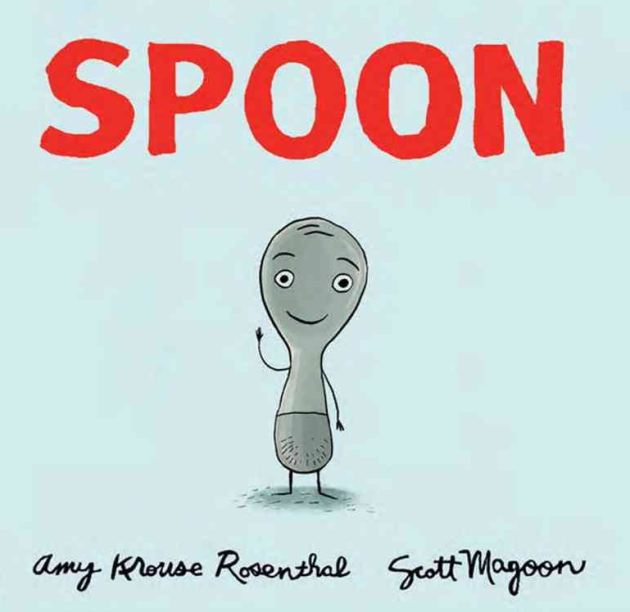

Yesterday my twins bit each other when an argument between them escalated rather quickly into a violent row. We were sitting at the kitchen table eating breakfast, and I was just about to read aloud to them from Amy Krouse Rosenthal’s Spoon, a longstanding dinnertime favorite in our family. My husband and I had selected this book together during our “date night” out during our vacation in the U.S. last summer, when his mother watched our kids so that we could have an evening to ourselves outside of the home. We got in the car and drove straight to Barnes and Noble, where we spent our kid-free evening—um—picking out books for our kids. Spoon caught our attention immediately because of its fetching illustrations of anthropomorphized cutlery—the spoon on the cover has wide eager eyes and a friendly arm raised in greeting.

Yesterday my twins bit each other when an argument between them escalated rather quickly into a violent row. We were sitting at the kitchen table eating breakfast, and I was just about to read aloud to them from Amy Krouse Rosenthal’s Spoon, a longstanding dinnertime favorite in our family. My husband and I had selected this book together during our “date night” out during our vacation in the U.S. last summer, when his mother watched our kids so that we could have an evening to ourselves outside of the home. We got in the car and drove straight to Barnes and Noble, where we spent our kid-free evening—um—picking out books for our kids. Spoon caught our attention immediately because of its fetching illustrations of anthropomorphized cutlery—the spoon on the cover has wide eager eyes and a friendly arm raised in greeting.

Only when we began reading did we realize that we were in the hands of a witty, word-loving wonder of a writer—which is to say that her Spoon was in our hands. The eponymous Spoon, we learn, is jealous of the knives and forks, who get to cut and spread and who never go stir-crazy. But then Spoon’s mother reminds him that only he gets to dive head-first into a bowl of ice cream and relax in a hot cup of tea, and Spoon begins to appreciate what only he can enjoy.

The book, on one level, is a simple tale about being content with one’s lot. As indeed, it seems, Amy Krouse Rosenthal was as well. Two weeks ago she had broken my heart and the hearts of thousands of other New York Times readers with her Modern Love column entitled “You May Want to Marry My Husband,” about her love of life and the love of her life, her husband of 26 years whom she would soon be parting with because she was tragically dying of terminal cancer. Just that morning—yesterday morning—I woke up to her obituary, which I read in bed on my iPhone before any of my kids had roused. I got out of bed, tiptoed to the kitchen, and set our copy of Spoon on the kitchen table, where it served as a sort of grave marker—a sad reminder of what is no more, and what still endures. When my kids woke up, I told them we’d be reading Spoon at breakfast, though I didn’t say why.

“This is Spoon,” the book begins, and then we turn the page and are greeted by a motley assortment of elderly and proper silver spoons, young teaspoons holding on to the hands of their mothers the tablespoons, and a baby measuring spoon linked by a ring to his older sibling: “This is Spoon’s family.” A few pages later, we hear about Spoon’s “adventurous great-grandmother who fell in love with a dish and ran off to a distant land.”

My kids listened attentively, as they almost always do. I have made it a regular practice of reading to them at the table so that they won’t argue—they are 5,4,4 and 1, and hence too young for proper table conversation. If left to their own devices, they will grab each other’s spoons, stab each other with plastic knives, and fork over any food they don’t want on to one another’s plates. And so I read to them as a way of maintaining order. It usually works, except when it doesn’t.

“Read it in Hebrew!” my daughter stays my hand as I try to turn the page. “No, the book is in English, she has to read it in English,” my older son insists. “But the last time we read this book in English. Now it’s time to read in Hebrew.” I work as a translator, and many of the books I translate are rhyming picture books. I enjoy the challenge of rhyme, the constraints imposed by the illustrations, and the opportunity to play around with words and sounds. Often I “test out” potential translations on my kids, reading them books first in the Hebrew original and then in my English translation to see if they have any suggestions. “All right,” I say. “I’ll read the book in English and then in Hebrew.” “I know,” says my son. “You can read one page in English and then one in Hebrew, and keep switching.” “No,” insists my daughter. “Hebrew!” Her twin shrieks, “English.” I put down the book and turn to my baby to spoonfeed her a few bites before I return to reading. But the moment I turn away, the twins give up on language and bite each other, ignoring their food, the book, and my own protestations.

Sometimes I wish my kids could get along better, like Fork and Knife and Chopsticks, who assure Spoon that he, too, has what to offer. My children’s cutting remarks to one another are hurtful to witness, and often I lament that I can’t spoonfeed them the values I so fervently wish to inculcate. But this doesn’t stop me from trying. When I put them to bed last night, lying between them just as Spoon “spoons” with his parents in the silverware drawer on the last page of the book, I reminded them of their fight at breakfast. “You can’t bite each other just because you don’t agree on what language to read in,” I said, and I wondered if Amy Krouse Rosenthal would approve of my attempt at literary criticism.

Please wait...

Please wait...