The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

January 31, 2017 by Eleanor J. Bader

“Not too long ago, some of the people who broke U.S. law to come into the country were Jews.”

As Donald Trump moves forward with plans to build a racist barrier between the U.S. and Mexico, signs Executive Orders barring most refugees from entering the country, and temporarily halts the issuance of visas for people from Iraq, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen, many of us are angry and ashamed.

As Donald Trump moves forward with plans to build a racist barrier between the U.S. and Mexico, signs Executive Orders barring most refugees from entering the country, and temporarily halts the issuance of visas for people from Iraq, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen, many of us are angry and ashamed.

Historian Libby Garland, a professor at Kingsborough Community College in Brooklyn, NY, shares these sentiments. At the same time, as a longtime researcher specializing in immigration policy, she is able to put today’s conservative momentum into a broader political context.

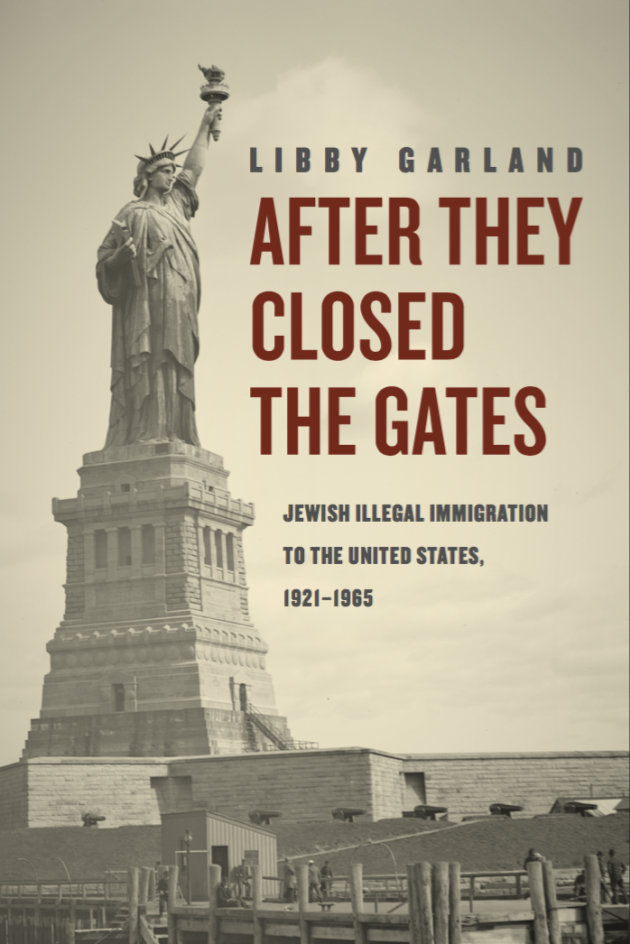

Her first book, After They Closed the Gates: Jewish Illegal Immigration to the United States, 1921-1965 [University of Chicago Press, 2014] looks at the impetus behind two exclusionary quota laws passed by Congress in 1921 and 1924 that were meant to limit the number of newcomers entering the United States. “The quota laws grew out of a widespread belief that some kinds of foreigners could be kept out of the nation, and out of a certainty that these groups could be recognized, counted and stopped from entering,” she writes.

Garland’s fascinating and painstakingly detailed analysis reveals that thousands of Jews—exact numbers are, of course, unavailable—opted to break the quota laws and enter the U.S. illegally. Desperate to leave anti-Semitism and poverty behind them, they traveled from their countries of origin to Canada, Cuba or Mexico, hoping to evade immigration authorities as they crossed into the goldene medina. Some purchased forged documents; others donned disguises. The lucky ones became what we now call undocumented aliens.

After They Closed the Gates not only charts the movement of these intrepid men and women, but also looks at the development of pro-immigrant advocacy and social service organizations within the Jewish community. Groups like the American Jewish Committee; The Hebrew Sheltering and Immigration Aid Society [better known as HIAS]; The Joint Distribution Committee; and the National Council of Jewish Women were heavily invested in helping individual Jews become legal residents. Furthermore, they encouraged activism to overturn the quota system they hated—an effort that finally succeeded in 1965.

Garland sat down with Lilith reporter Eleanor J. Bader one day before Trump ordered the Department of Homeland Security to begin planning construction of a wall between the U.S. and Mexico.

Eleanor J. Bader: I know almost nothing of my family history, but it never occurred to me that my grandparents might have entered the U.S. illegally. Did you learn of illegal Jewish immigration from your family?

Libby Garland: No. It had not occurred to me either and led me to question the reason for this omission. I learned about illegal Jewish entry by accident. In 1998 I was working on a dissertation in the American Studies program at the University of Michigan. I was interested in the transnational approaches to studying race, ethnicity and nationality and was delving into the work of aid organizations in the post-World War I era. I’d originally planned to compare the work of immigrant aid groups working with Eastern European Jews in Berlin and New York after the war.

I started my research in New York. Later, I went to the National Archives in Washington, DC where I immersed myself in the records of what was then called the Immigration Bureau at the Department of Labor. I started encountering the stories of people referred to as ‘smuggled aliens’ or ‘bootlegged aliens,’ people who were making their way to the U.S. despite the passage of new laws that were designed to keep them out. As I dug in, I realized that the impact of the drastic laws on Jewish entrants from Germany, Hungary, Poland and other countries was the story I should be writing.

Most of my own family members came to the U.S. before the quota laws were enacted, but over the course of working on the project, I learned about a lot of Jews who had family members who’d come over without papers during the quota era. Still, it was a conceptual leap to think about Jews as unauthorized immigrants, so-called “illegal aliens,” since Jews are never mentioned in discussions of undocumented arrivals today.

EJB: Why do you think this is?

LG: Illegal alien-ness became racialized in new ways in the U.S. after the First World War. As illegal alien-ness was increasingly racialized and directed at others, particularly Mexicans, the growing idea of Jewish whiteness distanced them from Latinos and Latinas. As a result, Jews were no longer seen as irredeemably alien. Finally, it’s important to note that Jewish groups themselves fought against the association between Jews and “illegal” immigration.

Long before World War II and immediately afterwards, Jews still had plenty of anxiety about their national membership status. This was not necessarily racial, but it was nonetheless acute. In the post war period, Jews started to be seen as less different from mainstream Americans. They became citizens, they voted for Democrats, they moved to the suburbs. The assimilation of the second and third generations further led to a whitening process. This was a major shift.

EJB: Did Jewish advocacy groups use whiteness to help the undocumented become legal?

LG: You didn’t find Jewish advocacy groups explicitly using whiteness for leverage. They talked about the U.S. as a haven, criticized unjust laws, and brought specific people’s cases to lawmaker’s attention. But even if they never argued that Jews were better than other people and deserved to stay in the country because of this, they were white and invoked ideas of Jewish whiteness in indirect ways. When they made the argument that Jews would make good future citizens, for example, they were linking their cause to race, since for many decades the legal right to naturalize was denied to Asians.

EJB: How effective were Jewish advocacy groups?

LG: Jews had a particularly impressive network of organizations, many of them built by folks who’d come to the US in the pre-quota era—the American Jewish Congress, HIAS, NCJW, among them. They put together an array of legal and other resources and showed up, front and center, at every Congressional hearing. They also conducted naturalization drives because they understood the powerful difference between the rights granted to citizens as opposed to “aliens,” particularly in the realm of immigration law. They also worked with people one-on-one to help them get acclimated to US life.

Even today, Jewish groups like HIAS are active on refugee issues, not just for Jews, but for all refugees.

EJB: I was happy to see that NCJW was active in working with Jewish immigrants during the quota era, 1921-1965. Did they focus on helping women? Was there a gender dimension to their work?

LG: One of the popular tropes of the time was that women needed to be allowed to enter the U.S., or be united with their male relatives if they were already here, because they were ‘maidens at risk’ and needed the protection of men. But this was not the only argument NCJW used. Most of their advocacy was grounded in casework, and they spoke about the real impact of immigration laws on actual people. They were seasoned organizers who knew who to contact in Washington or abroad. For the most part, they presented instances of family hardship to show why a particular person needed a visa or why a negative visa decision needed to be changed.

These women were doing hard logistical work. As reformers they were unapologetically forceful players in the fields of law, policy and social service delivery. Cecilia Razovsky was head of the NCJW’s Immigrant Aid department in the 1920s. She was everywhere, a tireless organizer, and made sure that NCJW was not a women’s auxiliary but rather an equal partner in the immigrant aid world.

EJB: Did undocumented Jewish immigrants ‘out’ themselves or organize as unlawful entrants, similar to today’s Dreamers or DACA recipients?

LG: As I said, the Jewish community was active in opposing quotas and assisting newly arrived immigrants, legal and non. I did not run into instances where, like the Dreamers, they said, ‘I came in unlawfully but deserve to stay and contribute to U.S. society.’ Likewise, there was no sanctuary movement to contest deportations.

In some ways, I found myself wishing that I had found more evidence of the organized Jewish community’s standing together with other immigrants, particularly those who were most intensely targeted by the immigration regime—Asians, and as time went on Mexicans. There were some Jewish activists, like attorney Max Kohler, who argued that the quota laws and harsh enforcement measures applied the same discriminatory logic against European immigrants that characterized Chinese Exclusion, which dated from 1882, but he was pretty unusual in his willingness to draw these parallels. Similarly, some Jewish leftists made the case that anti-immigrant policies were part of a larger attack on working people and that the right response to this attack was interracial and interethnic solidarity.

EJB: It’s been more than 50 years since the quota system ended. Do you think the Trump administration’s changes in immigration policy will move back in that direction?

LG: The evidence so far suggests, sadly, that it will. Steve Bannon gave a 2015 interview in which he went into detail about how great the 1924 quota law was. The Trumpist rhetoric about preserving America from unwanted invaders feels very 1920 or 1880-esque. It feels as hateful as ever. By the 1960s the quota law was considered by many Americans to be an embarrassment, evidence of past generation’s racist thinking, something inconsistent with the nation’s ideals. Unfortunately, many people today are no longer embarrassed by the idea of an openly discriminately immigration system. I don’t know what Trump will actually do or how immigration policy will evolve. What I do know is that it is actually a lot harder to seal borders than it sounds, and no matter what the law is, there will be people who come in violation of that law.

When Jews and the Jewish organizations consider their own stance toward the issue in the coming years, I hope my work will remind them that not too long ago, some of the people who broke U.S. law to come into the country were Jews.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Lilith Magazine.

Please wait...

Please wait...